Following my move from New York to Los Angeles in 1999, I managed to be bicoastal for three years. I kept an apartment in New York and spent months at a time there. I was already an Iranian-American New Yorker, having moved to Manhattan with my parents in 1979. Now, my new West Coast lifestyle amalgamated my cultural identity as well.

In September of 2001, I had been visiting New York for a month or two. By the 10th of that month, I was ready to get back to Los Angeles and my budding relationship.

On the morning of the 11th, I was sleeping on my father's pullout couch. Even with my midtown apartment, I still spent several nights a week at my father's home, which he shared with my stepmother and my half-brother, who was 4. My little brother was the draw.

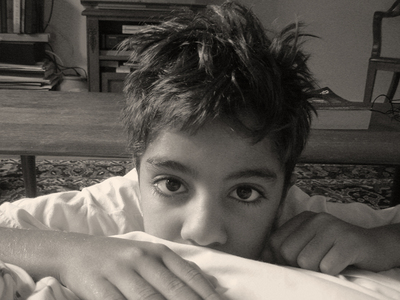

He had enormous, intelligent eyes, and his skin was the color of caramel. He used to hide in my suitcase so that I could "pack" him and "bring back to California" with me.

I was a late sleeper. When I slept on their couch, my little brother would bring his toys into the living room in the morning and play on the floor next to me. He would become louder according to the lateness of the hour, progressively waking me up.

But on the morning of the 11th, my entire family was in the living room with the television on. I had the covers over my head, as I'd become adept at sleeping through activity and noise.

"Hedia, Hedia," my father said. "Wake up. You need to see this. The news." I figured he was going on about yet another distressing political event in my home country of Iran, which my family and I considered ruined at the hands of the mullahs.

"It's OK, I don't need to know," I said in a sleepy voice from under the covers.

"Hedia!" Yelped my little brother. "An airplane flew into a building!"

I pulled the covers off my face and sat straight up. My stepmother had her hand over her mouth.

One of the twin towers was smoking at the top. Another plane was in view and looked to be flying towards the second tower. I was groggy and confused -- was there some sort of malfunction at air traffic control? How could the pilot not see the building?

And then... the other plane crashed right into the second tower as we were watching it, live.

Even then, we looked at the TV like there was some way, some chance, for it to end up OK. I was thinking of the earlier World Trade Center bombing in the '90s, after which they fixed the damage and everything went back to normal.

The point of impact, even with the thick obscuring smoke, looked small compared to the height of the building. We kept watching to make sense of it, not for an instant suspecting that we were about to witness the unspeakable.

The first tower crumbled in front of our eyes as if it were made of sand.

Shortly after, the second tower followed the same path to the ground.

It was -- and is still -- the most unreal sight I've ever beheld. There is a part of me that even now looks for the twin towers at the tip of Manhattan each time I ride in a car from JFK to the city.

On September 13, I put on a dust mask and carried two grocery bags full of produce so that I could pass for a below-Canal St. resident and get close to Ground Zero. It was true that only residents were allowed to cross the barricades, but I felt a strong need to feel connected to the scene. I could no longer bear the day-long, third-party accounts out of the television.

None of the officials questioned me. I walked past the barricades. I got to where smoke, dust and small debris still swirled in the air. It was a deserted world layered in beige. Parked and abandoned cars were covered in the beige dust as if it had snowed, and water from my eyes turned into mud.

The TV had affected my little brother, too; he kept running to turn it off. At one point, my father and I decided to take him for a ride. In the car, he sat on my lap looking out the window, transfixed by the passing buildings. Finally, he said, very thoughtfully: "I've been thinking, these buildings are too tall. I've noticed that planes often crash into them. I want to live in a short building."

I began attending a NYC elementary school in 1979 as a little Iranian girl just when the Iran Hostage Crisis had begun. Every day I was met with stares of intense hostility from the kids in my class, as if I had personally taken Americans hostage. What would it be like now, after an attack in what I considered to be my hometown, by Middle-Easterners, whom I also considered my people? By 2001, my family and I were far too assimilated in the quintessential melting pot that is NYC for any true concern. But I was still relieved to have an American passport now instead of my former Iranian one.

During the week of 9/11, I exchanged emails with various people in Los Angeles. This correspondence exists as a firsthand, real-time account of the aftermath. They are from the perspective of not just an Iranian-born New Yorker, but also a young woman concerned with ordinary struggles in the midst of extraordinary events. Had the world stayed the same on 9/11, I would've flown back that week to Los Angeles and my new relationship. Instead, airports shut down and I remained home for several more weeks.

The emails, some of which are edited and excerpted below, ranged from mundane to poignant. They covered everything from busy phone lines to my stepmother's post-traumatic panic attacks because she lived in Teheran through bombings during the Iran-Iraq war. They also documented my psychic shift from a numbed observer to one deeply affected on a personal level.

9/11 to 9/12/2001

The phone lines are still busy. My family and friends are all safe in their homes. They're shutting down lower Manhattan. My mother was stuck in Brooklyn until 4, but even she made it home on the subway. I only went out briefly to buy my stepmom flowers for her birthday...

...[My friend] Andre got caught in a stampede as he was walking by Bryant Park to go be with his dad, who saw the whole thing collapse from his terrace and was freaking out. It's Fashion Week, so tents were set up in that park, and as Andre walked by, they announced on the loudspeaker that everyone should evacuate. So all the models and designers and staff -- thousands of them -- stampeded the street, running north...

...They said that any non-residents or non-emergency personnel who try to get south of 14th Street tomorrow will be arrested on a Class B misdemeanor. They also need blood donors, and people have been lining up by the hundreds only to be turned away because the hospitals are out of plasma bags...

...The truck with explosives on the George Washington Bridge report is unconfirmed. [On the news] Peter Jennings was very adamant about differentiating between "extreme Islam" and "Islam." He seems appalled by the amount of people ready to go to war...

...Relatives told me that in Iran, they are broadcasting live via satellite and saying 200,000 New Yorkers have died. But the people in Iran know that number is propaganda...

...They closed ALL airports in the country today -- two million passengers. There are 30k - 40k flights a day on a normal day. I think it's going to take days and days for me to get back...

...My poor stepmother keeps leaping out of bed and running into the living room, asking me if I just heard an aircraft overhead -- you see, she spent 15 years in Iran during the war, going to bed every night with missiles landing all around her...

9/15/2001

I went all the way down to Chambers and Greenwich two days ago while they still had the police blockade. Snuck in through alleys and zigzagged streets where they just didn't have enough manpower. It simply felt wrong to be in the city for it and not even go near...

... Beige dust and papers and soldiers and FBI and wrecked cars and relief vans with juice and soda. Chambers is about 10 blocks away from WTC, so there was only small debris. The dust seemed an inch or two thick.

You should see the hole at the tip of island when you cross the bridge. I keep having nightmares. I never expected to live through a real war...

...Here too, people lit candles all over the city last night. It was beautiful -- and the weather was autumn-like, even chilly, so it sort of felt Christmassy with all that soft yellow glowing everywhere. What struck me was the fact that people continued to go about their business -- walking to grocery stores, sitting at cafes. Yet they brought their candles with them.

9/16/2001

I've been thinking that if there were a world war, it wouldn't feel right to hide when most of the rest of the world suffers. I wouldn't know another way to mentally survive a global war other than joining it. How could I really go about my business? What do my petty dreams of making films matter when the world is in turmoil?

...Everything seems cockeyed to me even if it all pretends to be normal. On the other hand, I can't believe that strange people are still strange in this city, and that swindlers still swindle, as if this should've modified everyone into something somber and solemn, like it did me...

...You must think that I'm utterly obsessed -- I never thought I could be so profoundly affected by events that don't ultimately have much to do with me. But there it is. I wish I had a paramedic license like you [so I could help]...

...You say people are volunteering so much because they want to feel like they're a part of something, but that's not what it is. It's that they feel connected to the rest of the human race, and they can't reconcile themselves to the fact that they're lucky enough to have their homes and family when there are other people majorly suffering. So they'll give blood, or donations, or raise a flag, or light a candle, anything to show -- not the world, but themselves -- that they live here too on the planet, and whether we like it or not, we're all linked...