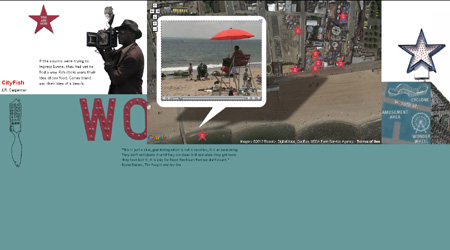

Screenshot from J.R. Carpenter's "City Fish"

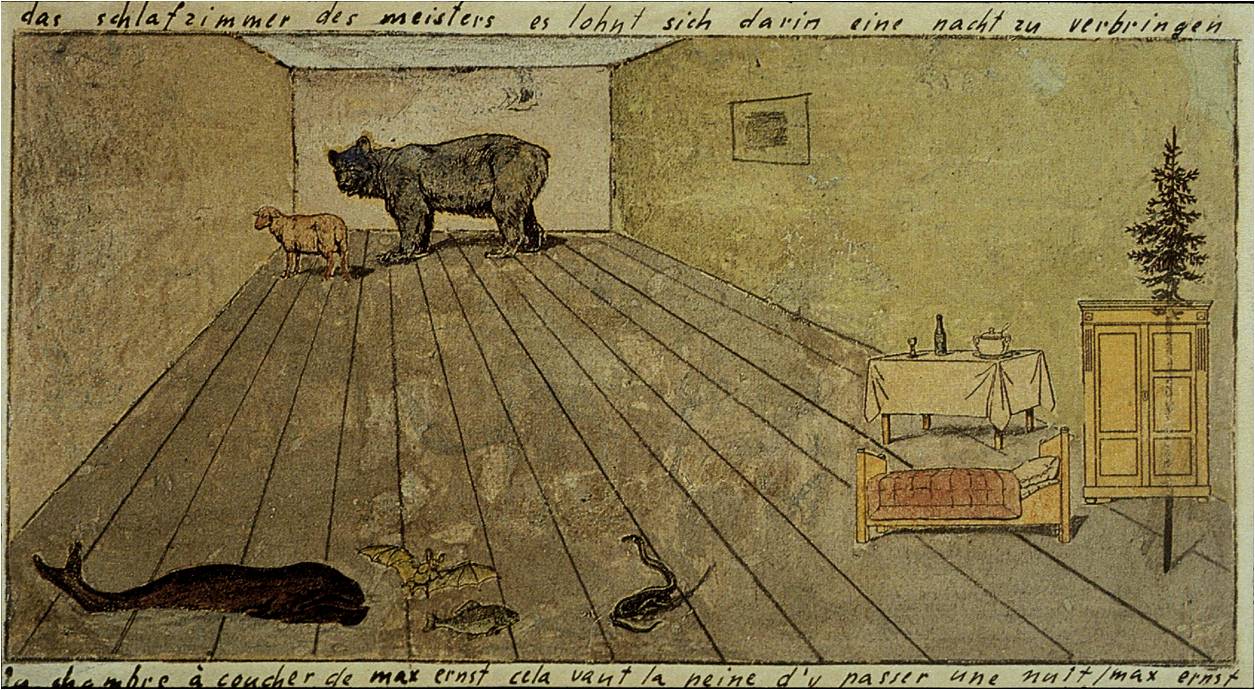

Decades before the birth of the Internet, Max Ernst created a collage drawing titled "The Master's Bedroom--It's Worth Spending A Night There." In an elongated rectilinear view, we peer into a room populated with furniture and animals. Ernst copied these objects from a page in a teaching-aids catalog, preserving the spacing, but including only some of the objects. The result is disorienting. We cannot resolve the disparities in size within the Cartesian confines of the room. Despite the allusion to an intimate, familiar domestic space, we find our selves in a very strange place.

Max Ernst, "The Master's Bedroom" (1920)

Now, of course, we have access to billions of virtual objects flowing, mingling, reproducing, redistributing, populating that non-place called cyberspace. In cyberspace, it is not physical landmarks and natural boundaries that orient us, but the patterns in which data is organized and presented which, in turn, depends upon code.

In much of her work, writer/artist J. R. Carpenter fabricates hybrid places that are both "virtual" and attached to real world locales. Like Ernst's bedroom, these online spaces contain objects whose appearance together makes sense only in the context of the artwork, in Carpenter's case, multimedia stories. Combining intimate details, both autobiographical and appropriated, of characters' lives with real-world maps and photo and video "documentation," Carpenter's works are narrative landscapes through which the reader meanders.

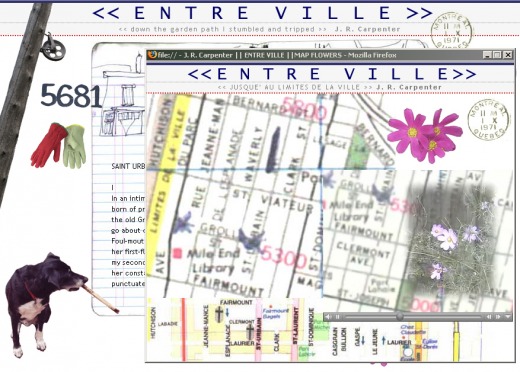

Screenshot from "Entre Ville"

For instance, the front page of Entre Ville (2006) contains a mismatched pair of gloves, a much larger dog, a telephone pole, a beat-up metal "no dogs allowed" sign, a graffiti-tagged number four and a trio of purple flowers. The effect is not surreal; we are used to processing information this way. Moreover, the text, a story of the open-windowed intimacies that Carpenter shares with her neighbors during a hot summer in Montreal, links this hodgepodge together.

Privacy, oven-bakedin an open-faced sandwich;

each apartment's gallery

trains a curious

opera glass eye

upon its neighbouring loge.Two yards over,

an empty swimming pool

gurgles above ground -

a waiting sound -

restless as nest-bound birds.Across the alleyway

a French man waits,

quietly, until dinnertime,

to aim his trumpet---J. R. Carpenter, Entre Ville

Clicking on windows and doors of the artist's notebook sketch of an apartment building, the viewer can explore the neighborhood. We access the artist's home movies -- ephemeral little films of her dog walking on the sidewalk, her curtains, the sound of a trumpet from an open window across the way. In this way, the reality of the virtual place is corroborated, not by any map, but by the banal domestic details of embodied existence.

I asked Carpenter how she incorporates code, which configures the spaces on the screen, into her art-making process.

J.R. Carpenter:In a large hypermedia work like "Entre Ville," for example, the steps I undertook before writing a single line of code included living in a place for years on end, reading books about that place by people from that place, walking and walking around and around that place, writing random notes to self, taking random photos, shooting video footage on borrowed cameras, collecting ephemera ranging from postage stamps to library due date slips... you get the idea.

I always start with a story. Even if the story is a poem. I almost never know what the final form of the piece will be. Even if the piece has been finished for some time. Some stories just don't seem finished, even after publication. I wrote the text of Entre Ville by hand on a hammock in Vermont. It was published in an online journal in 2005 Then I shot the video. Then I was commission by the Conseil des Arts de Montreal to create a piece for their 50th anniversary. Then I edited the video at OBORO, which took a month. Only then did I begin the web integration. The main interface was built around a line drawing I had made in a note book in 1992. I used pop-up windows because there were so many images of windows in the piece. There is nothing particularly complicated about the programming of the piece.

In "City Fish," Carpenter mixes autobiographical detail--memories of her visits to her Jewish grandparents in NYC in the 1970's with pure fiction. It tells the story of Lynn, a girl from Nova Scotia on summer vacation at her aunt and uncle's place in Queens. The viewer moves linearly to read the text and in depth (layers) to access other media elements.

Screenshot from "City Fish"

Clicking on the "You are here" star, the reader is transported to a part of the story containing a map of Chinatown and the Lower East Side, the artist's amateur video of Little Italy, and a bit of Lawrence Ferlinghetti's "A Coney Island of the Mind" which, for those in the know, evokes the fabulous Economy Candy store on Rivington Street (which Carpenter documents with video).

The pennycandy store beyond the El

is where I first

fell in love

with unreality

Jellybeans glowed in the semi-gloom

of that september afternoon

A cat upon the counter moved among the licorice sticks

and tootsie rolls

and Oh Boy Gum

-- Lawrence Ferlinghetti, "A Coney Island of the Mind"

In this work where the viewer travels rapidly between different times and places, appropriated and original texts, images and video (including a vintage TV ad for "The Whiz" electronics store), it is the story itself that acts as the thread holding the work together.

I asked Carpenter about her attraction to hybrid (real and virtual) places.

JR Carpenter:

I am a child of immigrants. I grew up in a different country than most everyone I'm related to. I wrote a lot of letters. When I got my first UNIX account in 1993 the internet was entirely textual. I didn't know much about computers, but the idea of writing across distance made great sense to me. My early adoption was due in part to my attraction to the internet as a placeless place, an in-between space, a repository for longing for belonging, for home. I've thought a lot about these nomenclatures. Web addresses, web sites, home pages, location bars, navigation. I've long thought of my early web-based works as sites, place-holders, stand-ins for pasts which could never be mine. "Mythologies of Landforms and Little Girls", 1997 was about a Nova Scotia I couldn't wait to leave, "The Cape," 2005 was about a grandmother I never knew, "How I Loved the Broken Things of Rome," 2005 was about the staggering gap between what is known of history and what is merely speculative.

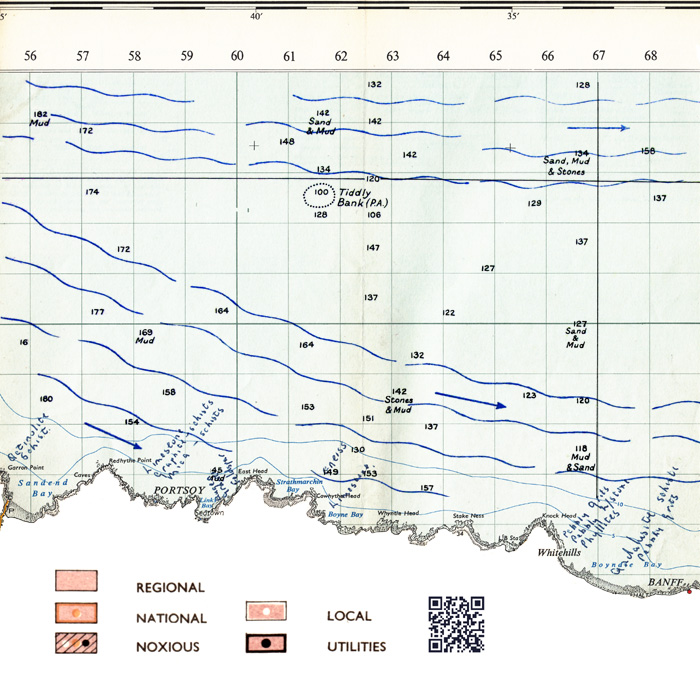

The ocean, bounded, yet always moving, altering second by second, is perhaps the ultimate unmappable space. Carpenter's "Broadside of a Yarn" appropriates the broadside -- a poster-form of street literature popular between the 16th and 19th century that featured proclamations, advertisements, descriptions of crimes, and the text of ballads. Commissioned for the ELMCIP (Electronic Literature as a Model of Creativity and Innovation in Practice) conference "Remediating the Social," the work is described by Carpenter as "a multi-modal performative pervasive networked narrative attempt to chart fictional fragments of new and long-ago stories of near and far-away seas with nought but a QR code reader and an unbound atlas of hand-made maps of dubious accuracy."

By incorporating QR codes, Carpenter directly invokes the hybrid spaces that cyberspace makes possible. Layers of information, from the author's own fiction to Wikipedia entries, are contained within the screen, but also overflow those boundaries in time and space.

Screenshot from "Broadside of a Yarn"

Carpenter references Situationist mapmaking in her artist's statement for "Broadside." Indeed, much of Carpenter's work can be seen as a virtual form of psychogeography in which the Debordian act of "dérive" or "drift" through an urban landscape, becomes a journey through cyberspace that incorporates both subjective experiences and objective limits.

In a dérive one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there. Chance is a less important factor in this activity than one might think: from a dérive point of view cities have psychogeographical contours, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes that strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones.

But the dérive includes both this letting-go and its necessary contradiction: the domination of

psychogeographical variations by the knowledge and calculation of their possibilities.

---Guy Debord, Theory of the Dérive

Like Debord, who remains acutely aware of the impossibility of a truly free ramble through space, Carpenter, too, grounds her fictions in the material details of life, which are sometimes boring, sometimes surprisingly poetic.

J.R. Carpenter:We spend more and more time online, yes. But live in a physical world, same as we've ever done. We eat we drink we fuck we sleep we shit we make things up we write things down. We made the internet, same as we made all the things that came before it. The saddle for the horse the road for the post the bridge for the river the compass for the ship the steamer for the packet the cable for the sea floor the satellite for orbit. We made the internet out of metal and plastic. It runs on electricity and air. A staggering amount of natural resources are consumed by this so-called virtual word. 30 billion watts and rising, according to the New York Times. Data centers our world.

Just as the construction of space in the real world is limited by natural laws (gravity, volume, density) and the properties of building materials, in the virtual world, it is the properties of the coding language that dictate how the environment will appear to us. Carpenter codes her own work, or appropriates existent code. In doing so, she is in essence recognizing the "materiality" of virtual space.

Screenshot from J. R. Carpenter's TRANS.MISSION [A.DIALOGUE]

The play of possibility within the confines of structured space which characterizes the dérive is evident in Carpenter's piece TRANS.MISSION [A.DIALOGUE] Here, Carpenter used source code adapted from Nick Montfort's story generator "The Two" to create a 42 line narrative dialogue generator.

J. R. Carpenter:One JavaScript file sits in one directory on one server attached to a vast network of hubs, routers, switches, and submarine cables through which this one file may be accessed many times from many places by many devices. The mission of this JavaScript is to generate another sort of script. The call 'function produce_stories()' produces a response in the browser, a dialogue to be read aloud in three voices: Call, Response, and Interference; or: Strophe, Antistrophe, and Chorus; or Here, There, and Somewhere in Between. Yet a reader can never quite reach the end of this TRANS.MISSION. Mid-way through a new iteration is generated. The sentence structures stay the same, but all their variables change."

In the virtual world, code is the equivalent of architecture, it is malleable but not infinitely extendable. For Carpenter, code is the foundation upon which digital stories are built.

J.R. Carpenter:Everyone should learn code. If not how to write it then at least how to read it. If not how to read it then at least how to read the signs of it. The word code comes from the Latin, codex. Until relatively recently, the fundamentals of Greek and Latin were taught in grade schools. Not because anyone thought that everyone would or should want or need to speak or write Greek or Latin on the mean streets of the 20th century, but because it was understood that the overwhelming majority of the stories we tell in the western world and the words we use to tell them derive from the structures, texts and syntaxes of these classical languages. By stories, I mean everything. Myths, legends, maths, logic, rhetoric. These days, in addition to the persistent influence of ancient Greek and Latin, the stories we tell are almost all touched by the structures, text, and syntaxes of programming languages. These words on this screen have been processed by my word processing software, which is itself a text too vast to ever read. They have been transferred through Internet protocols, which are also texts of sorts. The majority of text written and read by computers is never seen by humans. Yet all the same it shapes our every action. The most basic principals of the most common computer programming languages come from ancient Greek. Platonic Logic. If, than, else. If we understand this, then we have access to our stories. Else we fumble analphabetic through this encoded world we have set into writing.