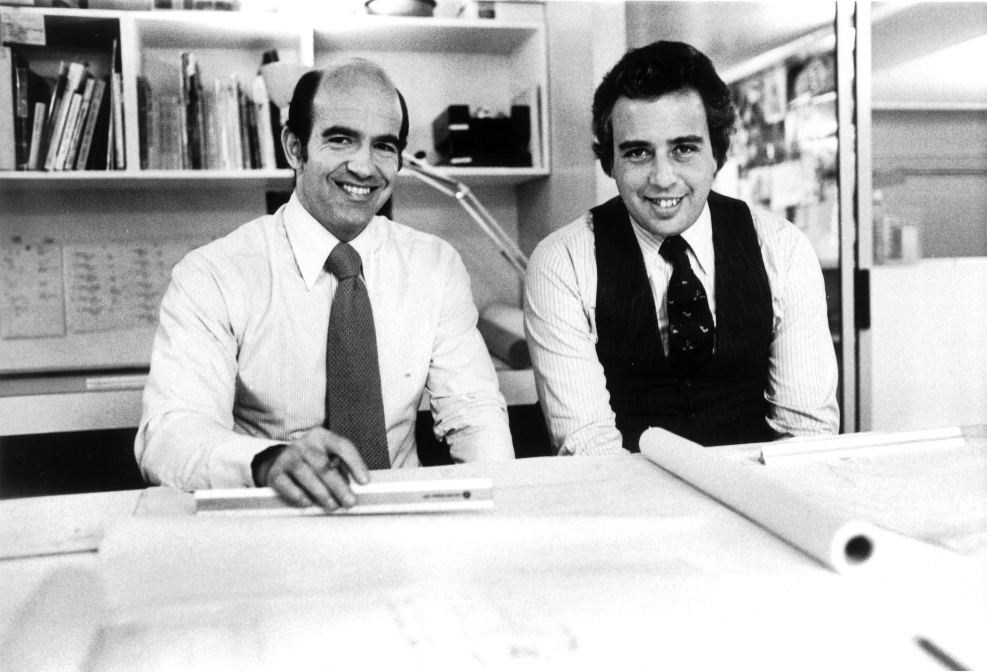

For the second time in two years, the work of modernist master Charles Gwathmey, his partner Robert Siegel and their architectural associates is on display in a building touched by Gwathmey's own hand.

This time around, the exhibition of their architecture is featured, appropriately enough, in Paul Rudolph Hall at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. In 2008, a year before his death at age 71, Gwathmey restored and expanded the 1963 building designed by Rudolph, dean of the School of Architecture during its construction.

Gwathmey was an apprentice to Rudolph -- a privileged position that spoke volumes about his talent -- during the building's design. He was responsible also for its original presentation drawings. Later, during his 40-year partnership with Siegel, he would take on highly sensitive expansions to the Guggenheim Museum in Manhattan, Whig Hall at Princeton and the Fogg Museum at Harvard:

"He was seen as the right person to do a sensitive response to the Rudolph building," says Robert A. M. Stern, current dean of the School of Architecture at Yale. "He had the imagination to introduce new systems for mechanicals, ventilation and lighting, completely of our time, and to enhance the building as well. It's wonderful to come and see the work, and see it in this building."

"Inspiration and Transformation" was originally curated by Douglas Sprunt for the Cameron Art Museum in Wilmington, N.C., which Gwathmey designed in 2002. The architect, suffering from esophageal cancer, was unable to attend the exhibit when it opened in 2009, though he did help to organize it.

Sprunt chose to look at the architect's relation with the art related to particular projects in his career. "That became the theme of the show," Sprunt says. "In a way, these residential projects were really where his most intimate investigation into architecture takes place." Most of the art is from the modern school, including works by Josef Albers, head of Yale's department of design.

The exhibition starts with a 1965 house and studio Gwathmey designed for his parents on Long Island. His father was a painter and his mother a photographer, but they also collected art -- and were a huge influence on their son. Among the items in the exhibit is Gwathmey's scrapbook from a year-long tour of Europe he took with his parents when he was 11. "It's amazingly informative -- the postcards are chronologically assembled," Sprunt says. "It shows how seamlessly informed his childhood was by his parents."

In all, the exhibition includes eight residential and institutional projects by Gwathmey Siegel, as well as Gwathmey's notebooks on Le Corbusier's work when the architect was abroad on a Fulbright Scholarship.

But it's his humanity that comes across most clearly. "Charlie was just amazing to work with," says the curator who worked closely with the architect to create the original show. "As accomplished an architect he was, he was a human architect too, and a lot of that had to do with his parents and his background in the South."

Stern agrees. "He could be a tough guy but he had a heart of gold," he says. "People adored him. He had a great gift for friendship."

Florida architect Alberto Alfonso experienced the full nature of the man as an undergraduate at the University of Florida in 1978. Gwathmey had arrived on campus for a lecture, to find students -- but no faculty -- in the audience. His lecture over, the students returned to their design studios.

"He came back to the studio at 10 p.m. and stayed until 4 a.m. We just talked," says Alfonso. "Later he wrote a letter to the dean, sort of scolding him -- you know, how could they design in a vacuum, and not show up for lectures?"

In 1995, when Alfonso won the Young Architect's Design Award from the University of Florida's College of Architecture, Gwathmey happened to be the guest lecturer at the awards banquet. And he remembered the former student with whom he'd once pulled an all-nighter.

"From the podium, he said: 'Hey Albert: I want to see your work -- let's have a drink," Alfonso says. "It was fate after that. He'd come down here or I'd be in New York, and we'd have dinner."

A little later came the references. "He designed (New York ad agency) Ally and Gargano's office, and he gave me Amil Gargano's residence to design," a still-astonished Alfonso says. "'I'm too busy,' he said. 'Do you want to do this house?' It was on Jupiter Island. You can imagine the faith he must have had had to refer that to me."

Gwathmey may have designed houses for celebrities like Steven Spielberg and Jerry Seinfeld, but he put the lessons he learned there to work on residential work for the less fortunate.

"From designing with people with money, he could turn his attention to tiny little apartments and townhouses, for people left out of the social system," Stern says. "He never designed down to them, but instead elegantly and meticulously planned small residential spaces with the same care in designing for the Steven Spielbergs of the world."

In two words, he was a class act.

"He had a kind of bigger than life, heroic image," Alfonso says. "He was a master architect who did great work."

The exhibition is free, open to the public, and on display through Jan. 27.

This post was changed to reflect that Alfonso won the Young Architect's Design Award from the University of Florida's College of Architecture, not from A.I.A.

For more on "Inspiration and Transformation," go here.

For more by J. Michael Welton, go to his Website.