One of the most interesting things about stress is that there is no universal agreement on what is stressful and what isn't. Ever noticed how your friend may love something that you truly despise? Whether it's roller coasters, climbing walls, or even public speaking, we all have different takes on how stressful certain activities are. So how is anyone going to define the word stress if we (including the experts) can't agree on what is stressful?

Nobody but me thinks about the definition of stress while trying to scale a climbing wall. But understanding why we get stressed and when we get stressed comes in handy when you are attempting to do anything new or challenging. You see, it doesn't really matter how tough you are or how fit you are, if you have a particular fear or phobia or stress about doing it, you are surely NOT going to do it as well as you could if you could learn how to manage that fear or phobia or stress.

Two days before the new climbing wall at my local gym was set to open to the public, I overheard a fairly well-built trainer in the hallway explain: "You are not going to see me on that thing, no way. I'm afraid of heights." So I was surprised to see him the next day, stepping into the harness getting ready to climb the wall. This was a guy, who could do a back flip from a standing position on a hard gym floor. So I was surprised to hear him say that he was afraid of anything. He started up the wall and seemed to be progressing just fine for about the first 12 feet and suddenly at 15 feet he just stopped cold. Even though he clearly had the physical strength to climb that wall, his mind (i.e., psychological stress) wasn't going to let him do it.

When I walked through the door to the gym the next day, I could feel a buzz in the room. It was the official opening day for the new wall. There was a crowd of people gathered at the base of it, all looking up, cheering each person who actually made it to the top. I decided to start with my usual workout routine, and try climbing the wall later when the line was shorter. As I worked my way through the room, I noticed my stress levels increasing rapidly. Just looking at that wall, knowing it was there, taunting me to climb it, sent my pulse racing, caused my palms to sweat and caused my gut to clench.

At this point I was experiencing something called anticipatory stress. With our vivid imaginations, we human beings create unnecessary stress, by imagining an event -- as stressful -- even before it happens. (And often what we imagine is much worse than what actually happens.) That's when I decided to just get in line and get it over with!

When another trainer started hooking the harness on me, I began to get really nervous. I could feel tiny beads of sweat dripping down from my armpits and hitting the sides of my chest. That caused me to experience a secondary stress response. In this case, I was getting stressed about being stressed. Experts tell us that the difference between professional athletes and the average person (and perhaps between you and your best friend) is not that this person doesn't have stress symptoms, but he learns how to peacefully coexist with those stress symptoms. I obviously wasn't quite at this level with wall-climbing yet, but I decided to go ahead and do it anyway.

Fatigue sets in fast when you are afraid, because your stressed-out mind is unnecessarily increasing your heart rate, tensing all your muscles (rather than just the ones you need to do the job) and thus making your body work twice as hard as it needs to. That's why a variety of (less in-shape) people, including a 10-year old child, and my best friend, had already climbed to the top of the wall with no problem. Fear wasn't holding them back.

However it wasn't long before fear and stress held me back, and I lowered myself down in defeat just like my trainer friend, having only climbed a little over halfway to the top.

That's when a really vicious form of stress called ego stress, kicked in. As I sheepishly stepped out of the harness, I could hear this voice in my head say: "A ten year old child can do what you are afraid to do. What's the matter with you?" It was then that I fully realized that my fear was (as the cognitive psychologists would say) irrational; that with the harness on, I couldn't possibly hurt myself. So what was I afraid of? Maybe what I was really afraid of was this voice in my head that -- at least on some level -- I knew would attack me if I failed to get to the top.

As I walked away from that wall I fought back with this voice in my head using self-compassion, newly minted mindfulness technique I'd learned about studying the work of Dr. Kristen Neff of the University of Texas. (See her TED Talk on self-compassion.) Dr. Neff points out how we Westerners unmercifully beat ourselves up, all in the name of motivating ourselves. But Dr. Neff's research indicates that this often vicious form of self-criticism almost always backfires. In the long run, we perform worse when we do this rather than better.

So I very consciously reassured myself, that at least I had tried to climb the wall. At another time in my life, I wouldn't have even done that. I also vowed to give it another try when I was fresh. So the very next morning, when I came into the gym, I headed right for the wall. I wasn't exactly feeling confident, but I was a lot less nervous than I had been the day before. It's no big deal whether you make it to the top, or not, I reassured myself mindfully. As I climbed up the wall I just kind of detached a bit from the voice in my head that was still trying to sabotage my best efforts: Almost like pretending I could only vaguely hear it.

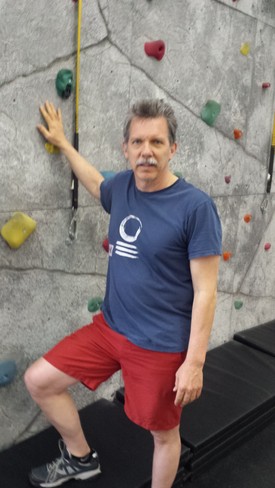

Using mindfulness strategies, I focused on my breath instead, taking one careful step at a time. When I finally touched the ceiling with my right hand, I felt a special pride that I hadn't felt in months -- overcoming an ancient fear and doing something completely new at 58 years of age. It was a great feeling. It was the feeling of self-mastery.

James Porter is author of the book Stop Stress This Minute and president of StressStop.com.