I'm going to be serializing an unpublished book, starting this week. It's about an amazing, mysterious manuscript I discovered in Scotland. It's a little book with nothing in it but 50 watercolor paintings. No one knows who painted it, or when, or where, or what it means. I was so entranced by this that I wrote a whole book of comments and thoughts on it. I call the book What Heaven Looks Like because the person who painted this was dreaming, I think, of an ideal world, a kind of heaven.

I thought it would be interesting to let everyone see this. Because no one knows what it means, you can suggest your own ideas, and we can build a collaborative interpretation.

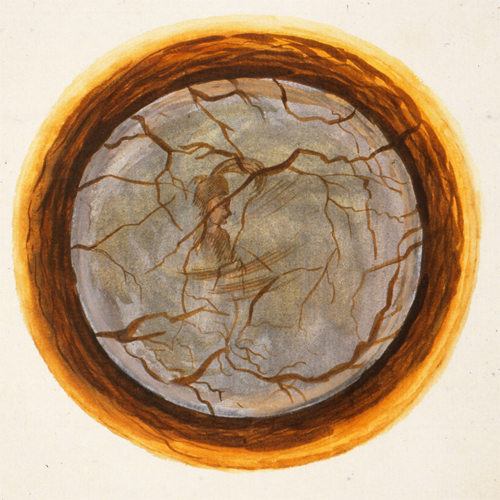

Many of the images are really astonishing, like this one:

He looks like a lonely Little Prince, with a big ostrich feather in his hat. He seems to be trapped in amber, or maybe he's behind a cracked glass window...

Here is another:

He's a magician, perhaps, or a magus. He's outside, in a snowstorm, in the night. His eyes glow like ice crystals, and a big snowflake, like a crystal ball, hovers in front of him.

Here is another:

At first it looks like clouds around a golden sunset. But there's an old man at the bottom, lying down. On the right there's an odd creature that looks a little (but not much) like a frog:

And in the middle there's another animal, a kind of bear or dog with spindly legs:

The whole book goes on like this. In this first post, I'm going to give the introduction, and the title page--it's the only writing in the entire book. Then, starting next week, I'll post the whole thing, image by image. Send me all your thoughts! When the book is published, I'll include everyone's ideas, and of course I'll credit everyone.

Preface

A woman sits down to her secret work. She lives alone--her husband has died, and her children have grown and moved away. The church lingers in her thoughts, but she is no longer sure what its stories mean. It is the very end of the Renaissance, and the old certainties are gone. Even the myths and legends seem wrong as they drift in and out of her solitary thoughts.

She goes out the back of her house and walks up a slope to a woodpile. She selects a cut log, and carries it back to her room. She stands it on the floor next to her chair, and she leans over to look at the cut surface. She studies the the drops of dew and the damp soft bark. She moves her fingers in gentle circles, following the fine brown rings in the wood. Cracks score the surface like spokes of a wheel. She tests them with her fingernail.

The wood is a lovely picture, made by nature. It means nothing and it says nothing, and yet it is full of faint colors, and, as she looks longer, faintly moving figures. She takes a small sheet of paper and begins to paint.

The book I will be posting here is a unique manuscript preserved in Glasgow, Scotland. The original is just pictures--no words, no explanations. No one knows who painted it, or when. I think it was created by a woman who imagined what she saw in the ends of firewood logs. In one picture the wood is fresh and green, in another old and cracked, in a third moldy and peeling. From that I deduce she worked at her project over a long period, perhaps years. I think she lived alone, perhaps high up on a forested hillside--at least that is how I imagine her. I have written this book to try to understand what she may have felt and thought.

Her pictures tell a strange and beautiful story of loss and uncertainty. She was deeply unsure about what she could believe. In her mind--an amazing independent mind, as striking in its wordless way as Spinoza's, or Milton's--the culture of community and belief had nearly stopped making sense. She thought hard about the Christian verities, and decided that little is known with any confidence. She was profoundly alienated from the dogmas of her day, and deeply skeptical about some the largest questions: the origin of the universe, the nature of God, and the possibility of heaven. She mused, too, on the loss of meaning in history and in human relations. I think of her as an irremediably lonely person.

In one sense, she was part of her time: the late seventeenth century saw an unprecedented erosion of faith, and a new awareness of inner life. At the end of this book, I have written about the artist's time, and the crises of religion, history, and representation that were in the air.

But in another sense, she is eerily modern. Her doubt and isolation are modern, and so are her paintings. There are things in this book that were not accomplished in art before surrealism: she plants glassy eyes in dark roots, congeals a patch of air into an amphibious face, turns a ram into a block of ice. Nothing escapes her oddly distorting eye: in one painting God himself is shriveled into a greenish lump.

This is an astonishing, wonderful book. It is mysterious, daring beyond anything else done in its time, and uncannily modern in its diffident, lonely skepticism. It is ravishingly painted, with a sure, free hand and a mind less burdened by the opinions of authorities than any other I know. It is one of the masterpieces of that half-lost, very modern moment between the faded Renaissance and the overconfident Enlightenment.

The Book

It is a small book in a brown binding. It has a title page, and after that there are only pictures--52 of them. They are in watercolor, and they vary in size from 110 to 130 centimeters in diameter.

There is a little secret about the book, which is not hard to discover: each painting is modeled on the cut section of a tree trunk. Sometimes that fact is hidden, as if it were an embarrassment. (After all, how could a true vision begin from a stump?) In other pictures, the tree trunk is perfectly clear, and the artist has lovingly painted the bark peeling at its edges, or the radial fractures that open when a log begins to dry. Wood is a leitmotif, a thought that keeps recurring. Some pictures are about wood--they show trees, or bushes--and others just use the wood as a springboard for the imagination. The artist never quite decides if the wood is important, and it is not entirely clear whether the paintings could have been based on stones or clouds instead of trees. The artist may have made the entire book from one special tree, carefully conserved as it dried and began to rot. (Some trunks seem to be damp with decay; others look like green wood.) Perhaps the artist went into the forest every morning and cut a new tree, like a Greek priest killing a fresh calf for each prophesy. As a romantic poet might say, the wood may even have come from a sacred spot--a churchyard or cemetery. One person who saw this manuscript said the artist used petrified wood, on account of the gleaming colors in some pictures. Wood is almost the only secret the book gives away, and in a sense it keeps that secret too.

That is about all that can be said at first look. The paper was made in Holland, toward the end of the seventeenth century. The artist may have lived in that century, or in the beginning of the next: the style tells us as much. But she (I think of the artist as a woman, for reasons I will explain toward the end) could have lived in Italy, France, Holland, or even England. Usually some telltale sign helps identify an anonymous artist: some stylistic quirk, or some figure or composition borrowed from another painting. At least so far no such clues have broken the manuscript's silence.

The Title Page

Here, in clear Latin script, is the only writing in the book. It says:

Work of Natural Magic, in which the Miracles of Pneumo-cosmic Nature are Painted with a Brush. Fully engraved by an Ape of Nature, following Nature's universal Catholic Prototype, and dedicated to the eternal memory of the king.

This kind of title is common enough in mystical and hermetic writing from the end of the sixteenth century through the middle of the eighteenth. Many writers were overwhelmed with the encompassing unity, divinity, and mystery of nature, and felt compelled to try again and again to capture it in words. "Pneuma" is breath, and so the "pneumo-cosmic" nature breathes with the spirit of divinity. "Catholic" and "universal" almost mean the same--that nature is everywhere brimming with holiness.

It's a little odd that the writer says the work is painted, and then immediately afterward says it was engraved, or modeled in relief (the word is ectypus). The two don't go together, and they imply that something other than ordinary art making is involved. I like to read the word for "engraving" as if it meant the same as "transcribing": that is, I think the artist meant to underscore the truthfulness of her unprecedented visions.

"Ape of nature" is also unexpected. Apes imitate, and they were often compared to artists, but it was never usual to be quite so forthright about the equation. But it was not uncommon for people with a mystical turn of mind to imagine themselves as apes in the larger scheme of the universe.

There are other clues in the title, and more could be drawn out of it. But it is important not to go too far. There is no evidence that the artist wrote the title page, or even knew about it. At least I have a hard time imagining a person thinking of such an unusual experiment (meticulously painting a series of hallucinations in cut tree trunks), one that may never have been repeated up to the present day, and then not wanting to say more than a few vague and evocative words about nature. In particular the flourish at the bottom of the page is careless and clumsy in comparison to the exquisite accomplishment of the painted scenes. How could they be by the same person?

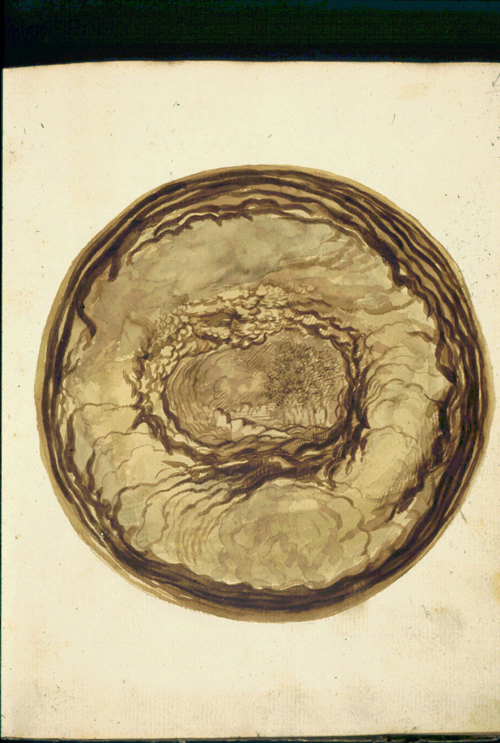

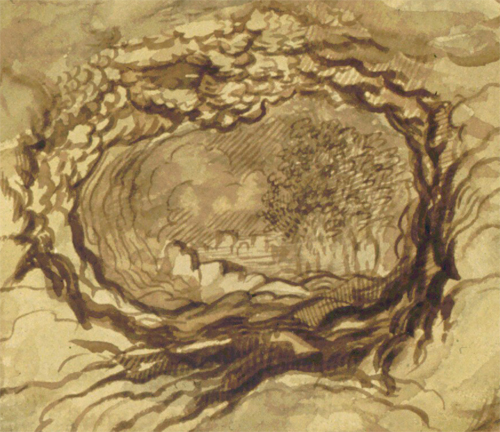

And then, after the title page, the pictures just start. There are no more words. Here is the first one:

And so we begin. The first scene is a landscape, with a city in the distance. It is seen through an opening--but what kind of opening? Stepping back, it looks like clouds, but looking closer it is apparent that the opening is lined with the roots, leaves, and trunks of trees. Or perhaps we are peering out of a cave.

The artist is expert in suspending judgment. Are we looking through opened clouds to a heavenly city? Or out of a cave--where we may have gone to hide, or to pray in solitude--back to the town from which we came? Or through a forest at a distant village? Or even--in the harsh, literal manner so fashionable in current criticism--through a womb, or into one?

Around the outside things get dark, as if to say we are in a hole within a hole, or peering out of one dream and into another. The artist loved these abysses, in which dreams jerk into waking life, or collapse into nightmares. We rarely know where we are, and when there's a foothold something on the margins is usually waiting to pull us away, or push us back into the deepest recess of a cave within a cave, within a cloud inside a dream.

The city is small in the distance, but it attracts our attention. There is not much to it: outlines of buildings, perhaps city walls and a gate. In front are a few blocklike forms. The clouds are full, and rain may be falling. When I have shown this to other art historians, they have sometimes recognized Giorgione's painting called The Tempest, which also has a city in the distance, ruins on the left, a grove of trees at the right, and a threatening storm. It is tempting to link this picture to that famous one, but Giorgione's painting was almost forgotten until romantic viewers revived it in the nineteenth century. Our artist may well have seen other Venetian landscapes, and felt an affinity with their half-ruined buildings and deserted pastures.

That's it for this first post! From now on, the posts will be shorter: just one image, and one page of thoughts about it. Follow the story, and add your ideas as we go!