During March, to mark seven years since the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the Shadow Elite column has been focusing on what I call in my book the "Neocon core," a tiny circle of longtime ideological allies who used their interlocking relationships across government, think tanks, business, and national borders to achieve their vision of asserting American power, and firepower, to remake the Middle East. This week: how I came to understand the core's modus operandi: through my experience studying the mechanisms of power and influence in post-Cold War eastern Europe.----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you were to look at the bulk of my three decades of experience, research and expertise, you might find yourself asking, what does a social anthropologist who spent much of her career specializing in eastern Europe have to say about the neoconservatives who helped take the United States to war in Iraq?

When the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, I was in Warsaw, having already spent some four years in the region throughout the 1980s. And in a twisted sort of way, examining eastern Europe up close--through its transformations away from communism over the last quarter century--has been excellent preparation for making sense of how a small group of power brokers helped engineer the invasion of Iraq, and more broadly, how a new system of power and influence has taken hold globally, one that, as I write in my book Shadow Elite, undermines democracy, government, and the free market.

In communist Poland, the necessity of getting around the state-controlled system created a society whose lifeblood--just beneath the surface--was vital information, circulated only among friends and trusted colleagues, information that was not publicly available. Under-the-radar dealings that often played on the margins of legality - this was the norm, not the exception.

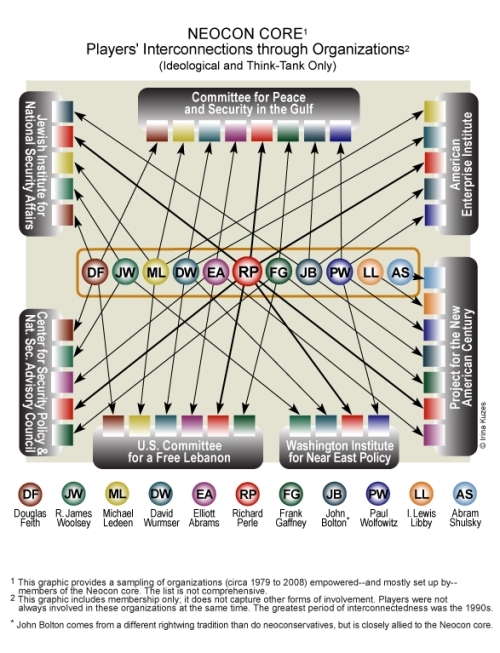

Then, in 1989, the system collapsed in eastern Europe, and in 1991, the Soviet Union came apart. The command structure of these centrally planned states that had owned virtually all the property, companies and wealth broke down and no authoritarian stand-in was put in its place. The result? Long-standing informal networks, positioning themselves at the state-private nexus, rose to fill leadership vacuums and, at times, reaped the spoils of previously state-owned wealth. Known variously as "clans" in Russia, "institutional nomadic networks" in Poland, and by still other names elsewhere, always their members were energetic and well-placed, sometimes also ethically challenged. And these are networks that can't be reduced to a political party, business or lobbying organization, NGO, social club, yet they have some of the attributes of all of them. Fast forward from transitional eastern Europe to this decade in the United States. I began to recognize a familiar (to me) architecture of power and influence. I started to follow the networks and overlapping connections in government, foundations, think tanks, and business of a tiny set of neoconservatives - just a dozen or so players I call the "Neocon core".

Some core members have been working together from in and outside of government for some 30 years to refashion a more aggressive American foreign policy. They have capitalized on an ever-more hospitable environment shaped by such trends as the hollowing out of the state, the explosion of private entities that fill in for government, and the questioning of authority and professional expertise.

In doing so the modus operandi of the Neocon core bears a strong similarity to that of the networks that shaped government, politics, and business in eastern Europe. Members of the core formed an intertwined and exclusive network, not unlike Russian clans in the post-Cold War years who positioned their members in and around the state to best promote their group's political, financial, and other strategic agendas.

The playbook of the Neocon core seemed to come straight from that of the top players of transitional eastern Europe.

In both cases, players who already knew each other set up a host of organizations--organizations that seemed more like an extended family franchise than think tank, populated by the same set of individuals.

In both cases, a network of players straddled state and private involvements, conflating state and private agendas, and assuming multiple roles in and out of government, with a great deal of ambiguity surrounding those roles. Where does the officially-sanctioned power begin and end for someone who's been a government advisor (or official), a consulting firm official, then a think-tanker, then back as a government advisor? (Or frequently, a player will assume two or more of these roles of influence at once.) And while the title or venue may change, the loyalty does not: he serves the agendas of his network at the expense of the organizations he works for.

In this murky environment, ambiguity often serves the player's purposes and a single title doesn't even come close to indicating the real scope of a player's power. During my time in eastern Europe in the 1990s, many officials I was interviewing gave me multiple business cards bearing their different job titles.

But that is a model of transparency when compared to the Neocon core. Consider the title of Richard Perle, the linchpin of the core, during the run-up to the Iraq war: chairman of the Defense Policy Board. This moniker hardly conveyed Perle's ability to broker deals, connect people through decades of associations, and mentor, protect and promote other core members into key positions of influence. These promotions happened despite the fact that Perle and two other core members, Douglas Feith and Paul Wolfowitz, were investigated at various points during their careers by the U.S. government for alleged breaches involving classified information surrounding Israel. Journalist George Packer calls Perle the "impresario" of the Iraq war, "with one degree of separation from everyone who mattered."

And in both cases, power brokers personalized bureaucracy, bypassing official process while bending the rules. Perle acted much like a Russian blatmeister--a master manipulator at using informal contacts and privately-hoarded information to advance the cause of the core and its associates. Standard procedures were bypassed or circumvented and quite often disdained, not unlike the dynamics I saw in eastern Europe, where it was a given that the real power resided somewhere in the neverland of state and private.

Insiders variously placed in the bureaucracy under George W. Bush are strikingly unified in observing that members of the core thwarted established processes and bureaucracy. And they marginalized officials who were not part of their network.

The Neocon core had its people - loyalists - staffing two secretive offices in the Pentagon that dealt with policy and intelligence after September 11--the Counter Terrorism Evaluation Group and the Office of Special Plans. The core helped create these alternative structures to construct their own official versions of the Iraq threat, and then branded them as the most authoritative.

The specific modus operandi helped the core create this desired reality. And this is one of the key reasons that the actions of the core go well beyond simple corruption or old notions of conflict of interests. As a Washington observer sympathetic to the neoconservatives' aims told me, "There is no conflict of interest, because they define the interest."

And despite a new administration in Washington, not to mention the damage done to their credibility since the Iraq invasion, the Neocon core lives on, because networks like it are self-propelling, multipurpose, and enduring. Steve Clemons, head of the American Strategy Program of the New America Foundation said this recently to reporter Matthew Duss, writing for The Nation.

They always continue to sort of lurk in the framework and look for opportunities to animate their crowd and bring in their fellow travelers...

As a social anthropologist, my focus is not on whether the U.S. should have invaded Iraq, but rather how that decision was made, who made it, and what mechanisms of power and influence were used to make it. Paul R. Pillar, a veteran CIA officer in charge of coordinating the intelligence community's assessments regarding Iraq, described the march to war to me this way:

There was no process. . . . No one has identified a single meeting, memorandum, showdown in the situation room when the question was on the agenda as to whether this war should be launched. It was never discussed. . . . That is the respect in which this case is markedly different from anything I've seen in the past. . . . There's well established machinery for this . . . For the decision to go to war in Vietnam there was meeting after meeting, policy briefing after briefing. The Iraq war was qualitatively different in that there was no such process. . . . In Iraq such machinery never got used.

From my vantage point, the actions of the Neocon core should disturb Americans of any political stripe. By acting more like the cowboys of the so-called Wild East of the post-Communist era, these power brokers perfected this new system of influence, subverting the standards of accountability and transparency that a healthy democracy demands. Americans were left almost wholly in the dark about the most important foreign policy decision a nation can make: to go to war. And when I asked Secretary of State Colin Powell's Chief of Staff Lawrence Wilkerson how that fateful decision was reached, he echoed Paul Pillar: without hesitation, he said, "I don't know."

Linda Keenan edits the Shadow Elite column.