Bruce Bartlett has a nice piece in the New York Times this week on the (non-)relationship between the tax wedge and employment rates across countries. The wedge is the gap between what employers pay and what employees receive after taxes come out. Reduce the wedge, the theory goes, and since you're making employees cheaper to employers, they'll hire more of them.

Most economists believe there's something to this. After all, demand curves slope down, and all else equal, lowering cost should increase quantity. But the problem is demand curves move around a lot, and at a time like this, for example, the key determinant of hiring is going to be more demand. Even at reduce rates, employers won't "buy" more workers if they don't need them.

That doesn't mean measures like the payroll tax holiday are useless. For one, by increasing the after-tax wage, they put more money in people's pockets, and that in-and-of-itself creates more demand. Also, when the economy turns up and demand begins to come back, a cut in the tax wedge can give cautious employers a nudge to pull some future hires forward into the present.

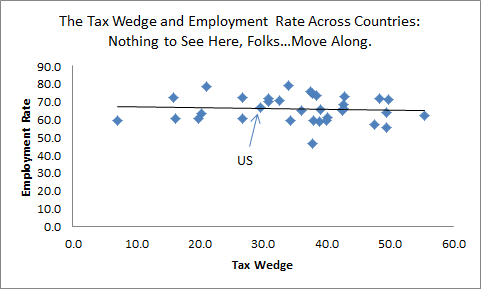

But as Bartlett shows, there's no correlation between the tax wedge and employment rates across countries. The figure shows the scatterplot. There's a slope there but it's nowhere close to significant and the R-square is 0.005, meaning there's no cross-country correlation between the magnitude of the tax wedge and the employment rate. A better test would be changes across time, and such panel data analyses find a bit more than the cross-sectional view. But not much. Here again, small responders win.

The three policy ideas I hear most often for greater job creation are cut taxes, cut regulation, and more education. While I support the latter, especially for those whose access is blocked by income constraints, none of these ideas will do much to increase the quantity of jobs.

What will? Greater consumer demand, an end to deleveraging, a growing housing market, more domestic production of the goods we consume, new innovations that generate hungry, job-creating start-ups financed by now-idle capital, clean energy investment, and if all else fails, a national program to rebuild and repair the nation's infrastructure, from roads to schools.

Boom...there's your jobs program. And I can think of policies that go along with each one of the above--in order: consumer demand: stimulus; housing: loan mods and principal reduction for some, time for others; more domestic production: weaker dollar, smaller trade deficits, manufacturing policies; innovation/start-ups: R&D, public/pvt/academic partnerships; infrastructure: FAST!

I'm being a little bit glib here...each one of those ideas deserves a lot more ink. All's I'm saying is that here is where the hard work is in terms of job creation--not in the passivity of failed supply-side, trickle-down, deregulatory BS (and I don't mean Bowles-Simpson).

Bartlett gets the last word:

The reason that unemployment is high clearly has nothing to do with taxes. Consequently, there is no reason to think that reducing taxes further will do anything to raise employment by reducing the tax wedge.

Source: Bartlett, NYT, using OECD data.

This post originally appeared at Jared Bernstein's On The Economy blog.