The Greatest Generation and The Beat Generation

As the Founder of The Beat Museum in San Francisco, I am often asked by tourists and scholars alike, "Why did you start The Beat Museum?" Specifically, why was I drawn to this group of nonconformists who never set out to change the world but who did so anyway because they followed their own individual passions? The Beat Generation, if you're unaware, was a group of literary and artistic intellectuals in postwar America whose themes could broadly be seen as Tolerance, Compassion and Inclusiveness of others. They influenced everyone from Bob Dylan and The Beatles to Hunter. S. Thompson and Johnny Depp.

And the answer comes from my own upbringing. I'm a baby-boomer and my parents are both members of The Greatest Generation. My father was born in 1926, the same year as Allen Ginsberg and Neal Cassady. And I grew up hearing very few stories of my father's youth and his war experiences. Like many of the men he served with during World War II my father came back from Europe in 1946 and all he wanted to do was resume a "normal" life -- settle down, get a good job, get married, have a couple of kids and a house in the suburbs, And like so many of the men of that era my father never really spoke much about his time at war. I had to pull the information out of him and, even then, the pulling was slim.

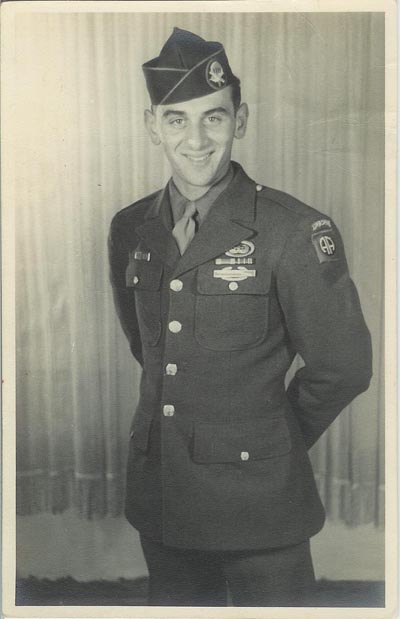

Jack R. Cimino, 82nd Airborne 1944I'd find things around the house once in a while as I got older. I actually found a German Luger -- the barrel was packed with mud if you can imagine -- my parents not wanting a gun in the house (not even a war souvenir) afraid one of us kids would accidently discharge it. I found a Nazi flag, medals, German coins. And then there were my father's own relics: his paratrooper's wings, Airborne patches and a Bronze Star along with snapshots and other souvenirs of the war.

Jack R. Cimino, 82nd Airborne 1944I'd find things around the house once in a while as I got older. I actually found a German Luger -- the barrel was packed with mud if you can imagine -- my parents not wanting a gun in the house (not even a war souvenir) afraid one of us kids would accidently discharge it. I found a Nazi flag, medals, German coins. And then there were my father's own relics: his paratrooper's wings, Airborne patches and a Bronze Star along with snapshots and other souvenirs of the war.

But dad didn't really tell me a whole lot about his time during World War II. He told me how he was eighteen-years-old, in combat for the first time during the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium in January, 1945 when a German machine gun opened up on their unit and they all hit the ground. Ice chips kicked up all around them and some of the guys started yelling for a Medic. They thought they'd been shot in the face when they felt the sting of the ice and the dripping of the water. And the old timers came up to them laughing, saying, "You Replacements. What are we gonna do with you. It's ice, you're not hurt."

82nd Airborne 325 GIR (Glider Infantry Regiment) 1945 (Cimino first row, third from right)

82nd Airborne 325 GIR (Glider Infantry Regiment) 1945 (Cimino first row, third from right)

Another story dad told occurred after the Battle of the Bulge when they were marching on Berlin. At one point he and another soldier were ordered to go in to inspect a bombed out bunker, something they'd been doing for days. After finding nothing the two came walking out to discover their buddies in the unit cheering in their direction. My father said, "I turned around and saw a bunch of German soldiers walking out of that damn bunker behind us with their hands on their heads. They'd been waiting in hiding to be sure they were going to surrender to American soldiers and not the Russians. We didn't even know they were there."

We kids all laughed. Dad always told us war stories that made us laugh as opposed to stories that would have scared us. He never told us about Wöbbelin, the SS Concentration Camp he and the 82nd Airborne liberated in May, 1945. Years later when I was an adult I asked him, "What did it feel like when those German soldiers marched out behind you?" "It scared the hell out of me," he said. "If it'd been a week earlier and they hadn't been so anxious to surrender any one of those bastards could have shot me dead."

Jack Cimino's Scrapbook for the War

Jack Cimino's Scrapbook for the War

As you might imagine, compared to many people, I had an idyllic childhood and our family lived the American Dream of what everyone aspired to at that time. My father was the man in the grey flannel suit and my mother was the original liberated woman working outside the home and raising two children in the 1950s and 1960s.

Today my father lives in retirement in Florida at the age of 85, still married to my mother sixty plus years later. They were born at the same time and lived through the same events as the original members of The Beat Generation. I wanted to know why the Beats took the nonconformist route and my parents the alternate "safe" course that most people took.

Jack and Lorraine Cimino early 1950s

Jack Kerouac, ever the observer, had to write about what he saw. Allen Ginsberg needed to shout from the rooftops about his world and his friends. William S. Burroughs suffered through his demons and wrote to exorcise them. And Neal Cassady had to march to his own drummer regardless of the consequences.

And what I discovered is sometimes heroes don't write books or have books written about them. Some heroes don't change a generation or a culture or the course of a civilization. Sometimes they just go about their business and lead quiet lives. And they suffer their moments and they live their times of glory, none of which are ever celebrated in story or song. And the only people they influence are those who are closest to them.

And they're heroes just the same.

Here's a recent newspaper article about my father and The Greatest Generation and how the War Reunions of the old soldiers are growng pretty thin.