When Elena Gitelson began experiencing back pain toward the end of 2012, she did what any hospital doctor might do: took herself to get a CT scan. A Russian-born oncologist at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Gitelson thought the pain was related to exercise. Even though she treated cancer day in, day out, the notion that she might have the same problem her patients had did not cross her mind--until the scan results came back.

"I think our lives are going to change," she told her husband, Igor Astsaturov, an attending physician working across town at Fox Chase Cancer Center, over the phone on her lunch break. The CT scan had revealed a tumor in her pancreas and multiple lesions in her liver. She had metastatic pancreatic cancer. Gitelson, easing her pain with ibuprofen, gave a two-hour lecture to a group of cancer patients that afternoon, and went home with her husband to discuss the plan of action.

The plan they decided on followed the leading edges of cancer research. Step 1: grow her cancer cells outside of her body. Step 2: get her tumor's genome sequenced and identify any genetic mutations associated with cancer. Step 3: find experimental drugs being tested against those mutations. Step 4: test those drugs out on Gitelson's cancer cells in the laboratory. Step 5: if they found an active compound, treat Gitelson with it.

That was on a Wednesday. By Monday, Gitelson was lying on an operating table having a piece of tumor removed from her liver by a surgeon named Paul Curcillo, a colleague of Astsaturov's.

Astsaturov and a colleague at Fox Chase, Vladimir Khazak, minced the tumor and soaked the pieces in a gel that promotes cell growth. They anesthetized a group of five or six mice and made a small incision in each animal, then placed Gitelson's tumor cells under the skin of each animal. Forty-five minutes after the cancer cells had been removed from Gitelson's liver, they were securely transplanted to the mice.

Within three weeks, Gitelson's cancer cells were growing in all the animals. At the same time, she began a course of chemotherapy. While the tumors in her body were shrinking, they were growing inside the mice. Gitelson continued working, insisting that missing work would be the wrong sign to send to her patients, and unwilling to give up caring for them.

Astsaturov also sent bits of Gitelson's removed tumor to Foundation Medicine, a commercial company that performs genetic analyses. The company had agreed to provide the normally costly service for free. After four weeks searching for more than 200 genes commonly involved in cancer, technicians at the company identified three mutations in Gitelson's malignant cells: kras, p53, and c-myc.

In numerous studies, these three genetic mutations have been associated with cancer development and progression. In addition, tumors with these mutations often become resistant to treatment. "We knew then we were up against something really tough," says Astsaturov.

As he explained, myc and p53 are transcription factors. These genes tell cells which other genes are to be activated when the genetic code is read during cell reproduction. The myc gene has a role in activating cell metabolism, regulating survival, and the acquisition of resistance to chemotherapy. "These three factors all contribute to a fast-progressing cancer," says Astsaturov.

Gitelson had a good response to chemotherapy at first. She was on a regimen known as FOLFIRINOX, consisting of three drugs (fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan), which had led to improved survival times in a study of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Diagnosed in about 45,000 people in the U.S. each year, pancreatic cancer has few treatment options. At least half of all patients are diagnosed when the cancer has spread to another area of the body. Just two percent of patients diagnosed at that stage live beyond five years. Even among the 9% of patients diagnosed when the disease is confined to the pancreas, the five-year survival rate is just 24%.

Despite Gitelson's initial response--the liver metastases all but disappeared and the pancreatic tumor shrank to almost nothing--Astsaturov knew he was racing against the clock. The chemotherapy regimen is too aggressive to take long-term, and the mutations lurking inside her cancer cells could soon render them resistant to the medications.

In late 2012, Astsaturov called his mentor, Louis Weiner, director of the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, part of Georgetown University, in Washington, D.C. Now that he had tumors made of his wife's cancer cells growing inside a group of mice, Astsaturov needed a way to rapidly screen experimental compounds for any activity against those cells. He had heard of a technique that Weiner had developed with his colleague, Richard Schlegel (developer of the human papillomavirus [HPV] vaccine), and wondered if it might work. Weiner agreed to help.

Astsaturov drove from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., bringing with him a single mouse from his experimental colony. A scientist at Weiner's lab, Sandra Jablonski, sacrificed the mouse, removed the tumor, and placed the minced cells on a layer of fibroblasts, a type of cell commonly found in connective tissue, in a Petri dish. The cells began multiplying. Within a month or so, Jablonski had millions of cells. She could now begin his search for a medication that might work against Gitelson's tumor.

But time was running out. Six months after Gitelson started chemotherapy, her disease started progressing. She tried a drug called gemcitabine, but the cancer did not respond. Her doctor, Steven Cohen, added Abraxane to the regimen, but whatever minimal response was seen was gone within three months. Finally, in early 2013, she tried cabazitaxel (Jevtana), a drug that is FDA-approved for the treatment of prostate cancer. It didn't work. Gitelson refused additional FOLFIRINOX. She knew her treatment options had run out.

In the cold winter months of 2013, Astsaturov and his team were holding out hope that they might find an experimental treatment before it was too late. They screened a total of about 850 compounds for activity against his wife's cancer and also cancer cells from six other patients.

Around mid-February, Astsaturov found what he was looking for. One of the experimental compounds was highly active against Gitelson's cancer cells. And, it was active against several of the other cancer cell lines.

The version of the compound in Astsaturov's possession, though, couldn't be given to Gitelson. It was a reagent suitable for laboratory work only. The drug (Astsaturov won't disclose the name yet) isn't available in the United States. The only way for him to get some for his wife was to get it directly from China. But finding a reliable supplier was proving extremely difficult. He was working with the U.S. embassy in China, but even that approach could not guarantee the purity of the compound he'd receive.

Meanwhile, he was conferring with Gitelson's oncologist about trying immunotherapy or a vaccine to help prolong her life. She just needed to stay alive long enough for him to get her this compound.

She didn't. Gitelson died March 31 at age 55.

Astsaturov and his colleagues remain determined to investigate this compound for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. Their first question was why this compound seemed to work. What was the compound doing to his wife's cancer cells? Two weeks after her death, Astsaturov's student found the answer. A laboratory test revealed that the compound had eliminated the myc gene in her tumor cells. Oddly, in the other cancer cells lines, myc remained. Astsaturov had his first clue. Once the underlying mechanism becomes fully clear, researchers can better identify which cancer patients might be candidates for this new drug.

Now, the research is poised for its next steps. Astsaturov is continuing his laboratory studies of the compound and has raised about $130,000 to collect further data. Elsewhere, a phase I clinical trial of the experimental compound for the treatment of pancreatic cancer is in the planning stages.

In other words, Step 5 of his and Gitelson's plan will be completed--only it will be in other patients.

It's a direction that Astsaturov believes his wife would have wanted, having always considered herself part of the research, not its goal. "Elena was interested to know how we were progressing, not selfishly but because she wanted better treatments for everyone," he says. "Her heroism, her conviction, is what drove us all."

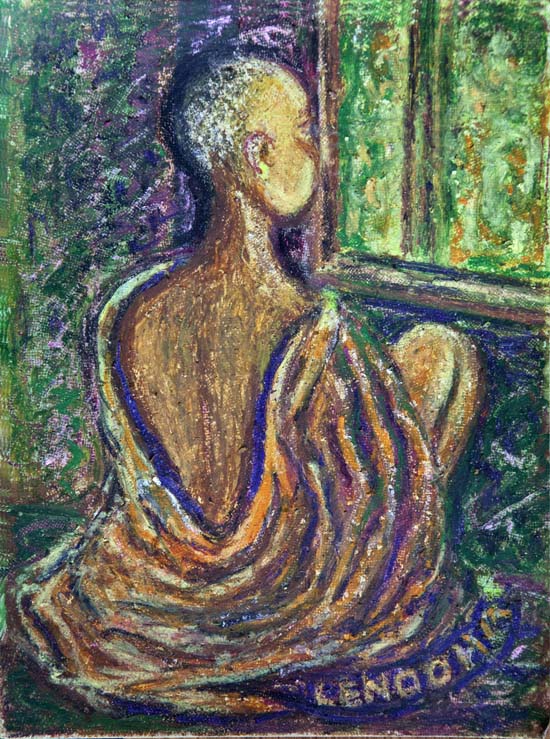

When I met Astsaturov this past May, at a talk I was giving at Fox Chase Cancer Center about my book, The Philadelphia Chromosome, which tells the epic tale behind a breakthrough treatment for an entirely different type of cancer, he told me how his late wife had been inspired by such past successes, and held fast to her vision of where genetic research could eventually lead - a vision she tried to capture in her artwork (those are chromosomes on the top right):

____________________________

Photograph of Elena Gitelson and paintings by Elena Gitelson provided by Igor Astsaturov