The first time I saw the ocean I couldn't speak a word. It was in San Francisco and a storm had just let up. The waves were double headers, but to me they seemed thirty feet high. All I could think was how little we matter, followed by these have NEVER stopped moving, not for a second. As I stared at the writhing vast ocean, I realized the nearest soil was Japan, half a world away. The magnitude of our insignificance started to set in, but not in an existential crisis sort of way, more of an existential alertness. Discovering one's scale can be incredibly therapeutic. The sea has been a constant informer of such things since the first man climbed aboard the first boat and pushed off into the open ocean. Falling off the edge of the world has always been the least of man's threats, though it took us a while to accept this.

November 14th 2013

36.582645n / --121.901556w

6:00 a.m.

55 °F

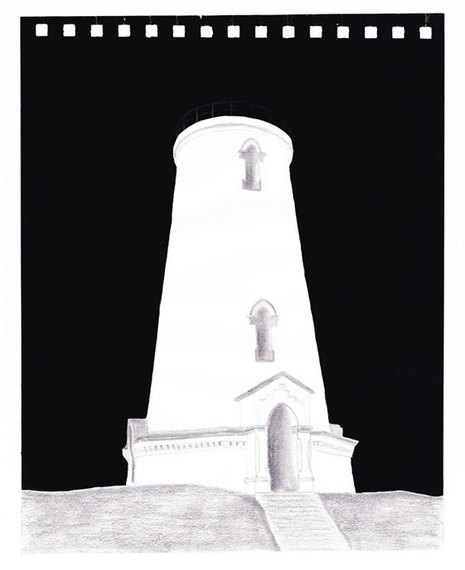

Last night, I spent several hours filming the Point Pinos Lighthouse in Pacific Grove, CA (36.6334°N 121.9337°W). I arrived at dusk and sat on the green of the golf course that surrounds the beacon. As the daylight passed, the fog rolled in slowly. It was illuminated by intervals of three seconds on, one second off pulse of the lighthouse's strobe that gave glimpses of the fogs details, an atmosphere which is hard to consider having detail. The cross bars in the lighthouse's tower cast shadows that divide the projected light into segments framing the beam and presenting it with a contrast that seems more cinematic than real (not unlike when smoke occupies the beam of a flashlight on a camping trip making you feel as though you have somehow captured its elusive motion even if only for a second). This isolation of the beam and shadow and their relationship play into the lighthouse as being a fictional character to people of our generation, where the use of GPS is far more common than the sailor perched atop a mast peering into the night.

I was grateful that my cell phone died soon after arriving at the Lighthouse forcing me to just sit while I shot the two films I had come to make. Sitting still is not one of my strengths. I am much more comfortable in motion thus being forced to sit still was of course a blessing, as all I could do was stare at the light which has been in continuous operation since it was first lit in 1855. There is something curious about a light I stare into daily (my iPhone) going dead allowing me to focus on a light that has shown nightly for more then 150 years.

It is not difficult to find romance in a lighthouse, nor is it a challenge to find a metaphor in a structure whose existence has always been to warn humans of impeding doom while allowing them to focus their attention on a safe passage.

The experience and human reaction to lighthouses has, however, changed dramatically over the years. I will likely never be able to image the feeling a forlorn sailor must have felt after months at sea when he laid sight on the slow pulsing light letting him know land was near.

If the sailor had been unaware of its purpose and sailed a direct route to uncover the mysterious light he would be drawn into the rocks and meet his doom, much like that of a Siren whose beautiful songs drew such men to their end. It is a curious thought, flashing a light at the point of danger and not the point of safety (Moth to a flame? The bright light often seen in near death experiences?). At times we should consider this in our daily lives, albeit more abstractly. Furthermore, we may acknowledge that one of the signatures of such a beacon is the presence of its eclipse, for the interruption of the light makes it a signal rather than a constant. Constants are easier to overlook or take for granted at times. In this absence, we are alarmed and alerted forcing our focus. The dark pause is as necessary to its purpose as the light itself in many ways.

j.frede : Point Pinos Lighthouse from j.frede on Vimeo.

December 1st 2013

35.137962n / -120.638080w

10:00 AM

72 °F

Last night I visited the Piedras Blancas Lighthouse Lens, which is now found in Cambria, CA (35.564691n / -121.096902w). The Fresnel lens of the First Order (the largest lens made, this one measuring ten feet tall including its structure) was removed from the lighthouse in 1948 after an earthquake damaged the lantern room, top section, lens and railing. This visually decapitated the classic storybook-esque lighthouse whose tall tower was much more prevalent on the eastern seaboard than the lighthouses that protect the pacific coast. A rotating aerobeacon was positioned on the now shortened and capped tower, which has allowed it to continue its duty but stripped it of its stoic posture.

Now positioned 14 miles from the lighthouse it belongs to, the lens stands still in a glass structure next to the Cambria American Legion, rotating only an hour at a time with a much quieter light than that which originally occupied the lens during its time in service. On Friday and Saturday nights, the lens' clockwork is switched on at 8:00 pm and rotates for one hour. Slowly rotating with bursts of light that come in four beams at a time from the dual lens panes that are positioned next to one another before the interruption panel followed by two more lens panels. The lighthouses had various arrangements and timings, which acted as a signature telling sailors which lighthouse was calling to them.

The land locking of a lifesaving beacon is a curious sight. Standing ever proud with precision and purpose evident to even the most untrained eye, the lens towers over the visitor and insists on our attention. Even now in its handicap state far from the sea, you can't help but feel you are seeing something just short of magic. To be given the job of a "Curiosity" when you were created for the sole purpose of saving lives, we have to ponder the consequences of displacing our warning systems completely out of our sight forcing them miles from their required location. Additionally let us consider a lighthouse light at ¼ power with the means to be seen up to 22 miles at sea but restricted to a glow. I could write for hours about the idea of displacement of possibility and purpose, but I will allow you to draw your own conclusions on this subject.

Ironically the lens is housed just off of a busy section of Main Street and while it spun I saw a number of vehicles slow down rapidly to see what it was and I had to wonder how many collisions had occurred due to the "light of safe passage".

I was able to get some good audio recordings of the lens' clockwork in motion. The sound of gears turning amongst one another and the shifting sounds of antique mechanics are a rarity in today's world. The sounds feel unstable with only the drop of a hammer at regular intervals acting as a constant. Such a soundtrack could be considered something of an aural time capsule or a glimpse into the past for us to hear the sound of precision parts of the last century working in harmony. As the antiquated mechanics reliably do their job they show no concern that they have been replaced in this world.

At 9pm the light went silent. Its beams slowed to a halt and its pseudo service was complete for the evening.

December 7st 2013

36.858838n / -120.456007w

7:00 PM

45 °F

Today I found myself waiting at a large metal door secured to the mouth of a tunnel, a hand chiseled tunnel which leads through a mountain to a gleaming white suspension bridge, a bridge that sways just enough to alert you that you have left solid ground yet sways little enough to demand your trust. Across the bridge stands what was the last manned lighthouse in California, Point Bonita in the Marin Headlands (37.815569°N 122.529604°W). This happens to also be the last lighthouse in California that uses its original Fresnel lens of the first order, whose light nods at me even in the bright daylight. As we crossed the bridge with a gaggle of sightseers, tourists and elderly couples, I had to remain focused to enjoy its romance while surrounded by other humans. All things seem more precious when one experiences them in the absence of strangers or surrounded by people of your choice whom you love and respect.

Does longing to experience the lighthouse in solitude stem from the history of the lonely profession of Lighthouse Keepers? To tour a lighthouse during the day makes things feel a bit out of place. Here we have a structure whose primary mission is to direct safe passage in darkness, who's strengths are greatest in the darkest hours of the night, while for humans such hours stir up some of our darkest thoughts forcing us at times to confront things we had put away during the busyness of the day. Was this true for the lighthouse keepers or did their demons arrive at the breaking of dawn?

Access to the lower quarters is granted by a National Parks volunteer who steadily recited a history of the lighthouse and surrounding area. His cadence and tone gave evidence of his continued passion and interested in what he was saying which made the information feel more valid. Exploring the small quarters, now crammed with visitors, I made my way through the rooms seeing familiar posters and items: the lighthouse keepers implements, blueprints of the Fresnel lens, scenic photographs of the lighthouse and the rubber stamps.

Unceremoniously laying on a back table next to scraps of waste paper and its well-worn inkpad, the "Point Bonita" rubber stamp is used by travelers that have found themselves obsessively visiting lighthouses collecting the stamps in a "lighthouse passport". I began to wonder about this stamp, which featured an illustration of the lighthouse perched above us, the artist unknown, yet their "art" was being collected by thousands who self "printed" the piece. This "print" instantly sealed that person's memory of the moment, which would hold fast the day for years to come. Imagine a piece of art, repeated countless times for years costing nothing (other than the energy it required to step out of routine and visit the lighthouse) and holding specific emotion and remembrance for the person whom pressed it slowly and steadily onto the page. The physical act of creating something that moments before did not exist gives the green outline of the lighthouse far more value than say a professionally printed pamphlet at the visitors center.

Moving my way back outside, I was pleased to see that the crowd had dispersed and I could stand on the deck and study the worn rusted lighthouse. Ringing the lantern room are the decorative heads of eagles or some imagined fowl, which felt more familiar to St. Vitus Cathedral in Prague than a humble lighthouse in Northern California. A spire reached to the sky from its roof and the slightest evidence of the lighthouse's subtle light in day time could be seen in the beveled edges of the lens, which stood in prominence filling out the lantern room like a large beautiful jewel with hints of rainbow reflections.

Heading back across the suspension bridge, we paused for a while from a good vantage point to take in the sight. You could see the light better from afar, its reliable beam coming on every four seconds defying the daylight and continuing on with its duty. Standing now facing the sea with the Golden Gate Bridge to my back, I realize I am aligned parallel to the shores where I saw the ocean for the first time more than twenty years ago. I still relate to the feelings I had at the time and acknowledge our scale. I am happy to see the vast sea too has remained steady in its approach and descent continuing on with its duty.

The films I made at Point Pinos Lighthouse and the Piedras Blancas Lighthouse lens are part of a series I have been doing since 2004 in which I film repetitive motion. The subjects are framed in such a way that usually makes the source undistinguishable. The films initially appear to be video loops and seem to be edited or computer generated. Only with time do the films reveal that they are actually long static shots of repeated motion as the repetition is broken either visually or aurally due to the introduction of something recognizable coming into view or a sound which allows us a point of reference.

The Repetitions Series has previously been presented as performance where I process and affect the audio live as the film is projected creating a slow moving soundscape soundtrack solely from its own elements and additional field recordings made during the filming. In 2004, I toured my previous films throughout Europe, capturing new footage along the way. In at least one instance the film I had captured during the daytime in a forest in Germany became the source material that evening in Zurich.

These new films allow me to work out the process with my current equipment before my residency begins. Kronstadt has twelve lighthouses, but I am unsure how many of these will be active considering the Baltic Sea may very likely be in a frozen state by the time I arrive. Their silence may be as interesting as their activity from a conceptual vantage point.

j.frede - 2013 | jfrede.com