When the Yale College Faculty passed a resolution in April condemning the "lack of respect for civil and political rights in the state of Singapore, host of the proposed Yale-National University of Singapore College" and urged "Yale-NUS "to uphold civil liberty and political freedom on campus and in the broader society," Yale's president Richard Levin declared that the resolution -- passed in his presence and over his objection -- "carried a sense of moral superiority that I found unbecoming."

Levin then unbecame what he ought to be as president of a liberal-arts university by going to Singapore and giving a speech at the end of last month, the same month in which that authoritarian corporate city-state had committed yet another of its abuses against basic civil liberties that have been monitored and condemned by many international observers and advocates -- liberties that, as the Yale faculty resolution emphasized, "lie at the heart of liberal arts education as well as of our civic sense as citizens" and "ought not to be compromised in any dealings or negotiations with the Singaporean authorities."

Yale President Richard Levin; Photo: AP

When Levin gave his speech touting the appointment of the ill-prepared but energetically pliable Yale professor Pericles Lewis as Yale-NUS' first president, Singapore had only recently prevented Chee Soon Juan, Secretary-General of the opposition Singapore Democratic Party (SDP), from leaving the country to give a speech of his own at the Oslo Freedom Forum.

Not only wasn't Chee allowed to leave Singapore; the International human rights lawyer Bob Amsterdam, counsel to the SDP and Chee's representative internationally, was detained and turned back at Singapore's Changi Airport when he tried to visit Chee on May 20, days days before Levin's visit.

So the Yale faculty resolution was right on target, and Levin's reaction to it was way off. Singapore's action prompted Thor Halvorssen, President of the Human Rights Foundation, to publish an open letter, here in the Huffington Post, to Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, urging the government to grant permission to Dr Chee to attend the event:

"In the last 20 years he has been jailed for more than 130 days on charges including contempt of Parliament, speaking in public without a permit, selling books improperly, and attempting to leave the country without a permit. Today, your government prevents Dr. Chee from leaving Singapore because of his bankrupt status.... It is our considered judgment that having already persecuted, prosecuted, bankrupted, and silenced Dr. Chee inside Singapore, you now wish to render him silent beyond your own borders."

According to the Associated Press, the Singapore "government's bankruptcy office denied Chee permission to travel to the conference because he has failed to make a contribution to his bankruptcy estate." But Singapore is infamous for prosecuting dissenters and opposition leaders for "defamation," thereby bankrupting them with legal costs and fines:

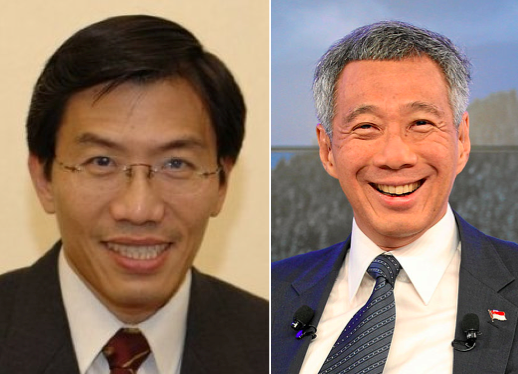

Opposition Leader Chee Soon Juan and Singapore P. M. Lee Hsieng LoongPhoto: Wiki Commons

"Supremely confident of the reliability of his judiciary, the prime minister [Lee Hsieng Loong] uses the courts ... to intimidate, bankrupt, or cripple the political opposition while ventilating his political agenda. Distinguishing himself in a caseful of legal suits commenced against dissidents and detractors for alleged defamation in Singapore courts, he has won them all," writes Francis T. Seow, a former solicitor general of the country.

For example, as I've recounted here, the first opposition politician to win a seat in parliament after Singapore's independence in 1965, Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam, was soon charged with defamation in a suit that bankrupted him and forced him out of public life. His was only the first prominent case in a relentless tide of prosecutions that shuttle dissenters, including NUS faculty, out of their jobs and homes and into unemployment, prison, or exile.

Chee himself, who holds a PhD from the University of Georgia and once taught at NUS, was fired from his post there as a lecturer in neuropsychology in 1993 after he joined the SDP party. When he attempted to contest his dismissal, he, too, was sued for defamation, bankrupted, imprisoned, and then barred from leaving the country.

When Singapore's apologists at Yale are forced to acknowledge such abuses, they explain them away as cultural differences or assure us that the country is changing. Yale astronomer Charles Bailyn, Yale-NUS' "inaugural dean," explains Singapore's bans on speaking at public demonstrations without a permit by saying. "What we think of as freedom, they think of as an affront to public order, and I think the two societies differ in that respect."

They differ in more ways than that: The SDP reports that "Chee declared bankruptcy in 2006 after he was unable to pay the fines imposed after he lost defamation suits initiated by Singapore's then-prime minister Goh Chok Tong and then-senior minister Lee Kuan Yew. He was also convicted on charges of libel during the 2006 General Election after both Lee Kuan Yew and the current prime minister, Lee Hsien Loong, sued him for implying corruption in an SDP newsletter. On top of not being able to travel out of the country, he has also been barred from standing for elections."

Amsterdam, the human-rights lawyer, has written a long white paper on such abuses by Singapore. Bailyn can't explain these away, but If he's still in doubt, he can learn more about the country's record and continuing practices from Yale student Luka Kalandarishvili, who wrote a paper on the subject for a seminar on "Global Journalism, National Identities" that I taught last spring.

Why is Yale disgracing itself this way? It's one thing for a business corporation to roll with the punches while dealing with clients, customers, and investors in countries that do things differently than ours does. It's also okay for a university to establish a small center or professional school that limits itself to transferring skills. It's quite something else for a liberal-arts college to transform itself, as Yale is already doing in New Haven, from the crucible of civic-republican leadership it has been into a career-networking center and cultural galleria for a global managerial elite that answers to no republican polity or moral code.

A liberal education is supposed to show the young that the world isn't flat, as neoliberal economists like Levin think, but that it has abysses that yawn suddenly at our feet and in our hearts and that require insights and coordinates far deeper than those offered by markets and the states that serve them -- as Singapore's state does to a fault.

Then again, Yale has been behaving as if it were a business corporation. As Amsterdam was being denied entry into Singapore last month, I was seated at a dinner in Germany next to a very high official of a European university who'd been to Singapore a few times himself. "There's $300 million for Yale in its deal with NUS," he confided to me.

"What? How do you know that?" I asked. "Yale claims it's not getting a dime from Singapore, although Singapore is paying all the costs of constructing and staffing the college itself."

"Oh, it's not a direct payment," my interlocutor explained. "It's what you call insider trading: Yale will be cut in on prime investments that Singapore controls and restricts through its sovereign wealth fund. These will be only investments, not payments, so there's some risk. But you'll Yale's endowment will swell by several hundred million in consequence of its getting in on these ventures."

This hit me with some force because, only a few weeks before, I'd written here that the real scandal in Yale's Singapore venture is Yale Corporation members' blithe assurance that they can do well by doing good, as long as they ignore the costs to republican liberty and the creativity and citizenship such liberty yields. When I think of Levin's envisioning the Yale-NUS arrangement, first at Davos, where it began, and then with his recent Yale Corporation members G. Leonard Baker, Charles Ellis (who maintains an investment business in Singapore and is married to the Secretary of Yale, Linda Koch Lorimer), and with Charles Waterhouse Goodyear IV (once the CEO-designate of Singapore's sovereign wealth fund, now a member of the Yale Corporation) the European university official's comment sounds right.

Take a look at this short video of yet another Yale Corporation member and Yale-NUS champion, Fareed Zakaria, interviewing Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsieng Loong at the Davos World Economic Forum last January, and notice the nuances of subservience: Zakaria, who would take to the pages of the Yale Daily News in April to disparage, as "provincial," those faculty supporting the resolution criticizing Singapore's abuses, never mentions Yale's venture with Singapore in the January interview, nor does he ask Lee about any of Singapore's human rights abuses.

The prime minister is a piece of work here -- British-educated, well-buffed and modulated, dispensing pellets of charm, a studied dignity in informality, and sinuous liberal bromides, with just the right hint of tempered steel behind the smile.In this, he is not unlike what Zakaria used to be, but study Zakaria's countenance and see the perfect mask of complicity and obeisance that recalls W. H. Auden's observation, in the Europe of the 1930s, that "Intellectual disgrace stares from every human face."

American college administrators, struggling to balance truth-seeking with power-wielding and wealth-making, are readily disarmed by operators like Lee and Zakaria. Our liberal arts colleges are vulnerable to market riptides, to putsches by would-be donors and moneyed interest groups, and to the stomach-turning descent of America's civic culture into brutal political speech, gladiatorial sports and degrading entertainments, all of it accelerated by those market riptides and the global capitalist wrecking ball. Small wonder that to the beleaguered Levin and his globe-trotting trustees, Singapore seems a port in the storm: The little city-state need "liberalize" only a little, and Yale need "Singaporize" a little, they think, for the fit to be as perfect as the mask that is Fareed Zakaria's face. They find the Yale College Faculty resolution "unbecoming" because it disrupts that fit and discredits that mask.

To its designers, the Singapore undertaking seems all the more harmonious convergence because, throughout Levin's presidency,Yale has compared poorly with other American universities in its support and practice freedom of speech, as I showed here at some length, and as Stephen Walt noted last week in a Foreign Policy post, "Yale Flunks Academic Freedom."

The Yale Alumni Magazine, which, unlike Harvard's equivalent, functions dutifully as a press office for Levin, finessing controversy after controversy to minimize its effects on his administration, has yet to inform Yale alumni that even though Yale-NUS graduates will not earn bona fide Yale degrees, they'll find the Yale name and logo on their diplomas and will be "fully integrated into the Association of Yale Alumni Network" -- a puzzling first, for reasons I've reported here.

The Yale Daily News has allowed its reporter covering the Yale administration to serve as a press officer for the administration, failing to report any of the irregularities in the Yale-NUS venture. (Find the section, "A Telling Default," in this long post.)

And the Yale Law School, of all places, has been obdurately, shamefully silent about the abuses by Singapore that I've mentioned. The law school can redeem itself by inviting Chee's lawyer, Bob Amsterdam, and Yale alumnus Bo Tedards, the global democracy activist who's been writing to Levin about the Singapore regime, to speak to what I'm sure would be a capacity crowd in the Yale Law School auditorium. Will it issue the invitations? If not, what is the law school for?

The Singapore venture has compromised Yale deeply not because Singapore is such an evil place in the larger scheme of things - it's an authoritarian, corporate city-state with a well-educated, prosperous populace that may surprise us someday by curbing and licensing its governors -- but because Yale itself has been led so crudely, cluelessly, and prematurely into this place where it need not have gone and where, pedagogically, can ill afford to go right now.

In his nearly twenty years as president, Levin has been invaluable to Yale as the pilot of its enhancement fiscally, physically, and in town-gown and labor relations, and just last September, I congratulated him for an address to incoming freshmen, whom he implored to be true to liberal education's skepticism of dogmas and over-simplifications. But now I think that I missed the note of desperation in his address: It was almost as if he were imploring 18-year-olds to save Yale from itself -- and perhaps from what he has done by choosing the Singapore venture as a way to make his mark and seize the future. He has been a very good manager with a very bad sense of liberal education's purposes and stakes and of what courage and choices are necessary to vindicate them in this world..

In the 1950s, Yale's president A. Whitney Griswold crusaded for liberal education against both McCarthyism and Communism, no easy task for a university president in those dark years. Levin has outsourced the equivalent challenge of our time by presuming to bring liberal education to Singapore, which becomes a laboratory for the decorous prostitution of liberal education to market riptides here at home -- all while enhancing Yale's brand name and market share, of course. The real cost is already being felt in the Singaporization, not cosmopolitanization, of Yale.

A sentence in this post that had stated, "Then again, Yale is a business corporation" has been altered to meet Yale's objection that the statement was not literally true.