On Thanksgiving night, the world will get a glimpse of Michael Jackson they have never seen before when Spike Lee's Michael Jackson: Bad 25 makes its television premier (ABC, 9:30pm EST). What follows is an exclusive excerpt from Man in the Music: The Creative Life and Work of Michael Jackson, which was used as a resource for Bad 25 and comprehensively explores the artist's entire solo career -- from 1979's Off the Wall to 2001's Invincible. The excerpt below comes from the third chapter, dedicated to Jackson's highly-anticipated follow-up to Thriller, the Bad album.

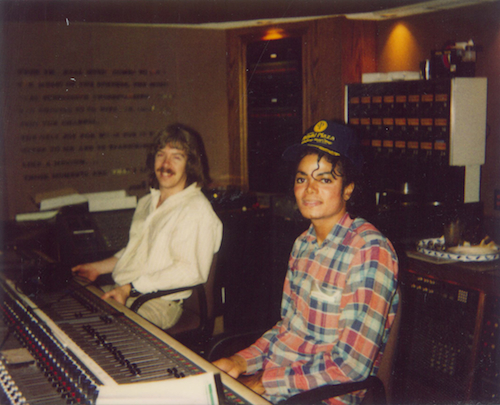

MJ in the studio circa 1987. Picture courtesy of ©Matt Forger. Used by permission.

Michael Jackson began work on what would become the Bad album in 1985. Three years had lapsed since the release of Thriller, and fans were waiting anxiously for the sequel. Following the most successful record in the history of the music industry, however, was not an enviable task.

Jackson added to the pressure, writing a note on his bathroom mirror that said simply: "100 million." That was his aim for Bad -- more than double the sales (at the time) of Thriller. With this ambitious goal in mind, he went to work.

In the early stages, he would simply go into his home studio at Hayvenhurst with musicians and engineers such as Matt Forger, John Barnes, or Bill Bottrell and work on ideas. Jackson called it "the laboratory." Here, he recorded dozens of 48-track demos in a variety of styles. It was a space that allowed him more freedom and spontaneity to pursue creative ideas.

Eventually a bit of a rift developed between what became known as the B-Team working with Jackson at his home studio and Quincy Jones's A-Team at Westlake Studios. "Michael was growing and wanted to experiment free of the restrictions of the Westlake scene," explained producer Bill Bottrell. "That's why he got me and John Barnes to work at his home studio for a year and a half, on and off. We would program, twiddle, and build the tracks for much of that album, send the results on two-inch down to Westlake and they would, at their discretion, rerecord, and add things like strings and brass. This is how MJ started to express his creative independence, like a teenager leaving the nest."

Many of the songs the B-Team worked on were practically finished before they reached Westlake. "He was able to take some finished demos into the 'real' studio with Quincy and that was his way of getting more say [in how they were produced]," recalls Bill Bottrell.

In late 1986, recording finally began in earnest at brand new Studio D at Westlake, where Jackson continued to work with many of the same key players from Off the Wall and Thriller, including recording engineer Bruce Swedien and keyboardist Greg Phillinganes.

Quincy Jones, meanwhile, continued to act as producer, though he and Jackson didn't always work together as smoothly as they had in the past. It was clear to everyone around Jackson that he was evolving and gaining more and more creative confidence and control as an artist (he would write nine of the eleven songs included on Bad, plus numerous others that didn't make it onto the record). This led to some collisions on production and song choices, as well as on the album's overall aesthetic vision.

"[Quincy and I] disagreed on some things," Jackson recalled. "There was a lot of tension because we felt we were competing with ourselves. It's very hard to create something when you feel like you're in competition with yourself."

In spite of the pressure and high expectations, most who worked on the album remember the atmosphere in the studio as one of "love" and "camaraderie" -- a creative climate attributed to both Jones and Jackson. Bruce Swedien recalls a tradition Jackson started called "Family Night," in which all the family members and friends of the studio crew were invited on Fridays to dinner in the studio prepared by Jackson's cooks, Catherine Ballard and Laura Raynor (affectionately nicknamed the "slam-dunk sisters"). Assistant engineer Russ Ragsdale remembers Jackson doodling all the time in the studio; he also remembers him enjoying getting out for a break. "On a few occasions," recalls Ragsdale, "Michael would want to get out of the studio for a bit. At the time I had a big full-sized Ford pickup truck with tinted windows. Michael loved riding in that truck and got real excited because he was able to sit so much higher off the ground than his Mercedes. We tried our best to just treat Michael like a regular guy. We didn't go out of our way too much."

As with Thriller, hundreds of songs were considered for Bad. From these, Jackson and Jones whittled down the list. "Fifty percent of the battle is trying to figure out which songs to record," Jones remarked. "It's total instinct. You have to go with the songs that touch you, that get the goosebumps going."

According to Rolling Stone, "Jackson had 62 songs written and wanted to release 33 of them as a triple album, until [Quincy] Jones talked him down." This trimming down led to some excellent tracks being left on the cutting room floor, including "Streetwalker" (which Jackson preferred, but was talked out of by Jones in favor of "Another Part of Me"), "Fly Away" (a beautiful, melodic mid-tempo ballad), and "Cheater" (a funky, gritty rhythm track), among others.

Once the songs were chosen for recording, the objective was creating sounds the "ear hadn't heard." Jackson didn't want to duplicate Thriller, or other music on the radio, for that matter. He wanted to innovate sonically. "Michael's vision [is] to start making a record by creating totally new fresh sounds that have never been heard before," explained Russ Ragsdale. "For Bad this was achieved with synth stacks filling up the entire large tracking room taking up every available space, as well as the largest Synclavier in the world at the time operated by Chris Currell. ... It took over 800 multitrack tapes to create Bad; each song was a few hundred tracks of audio." For the rhythm tracks in particular, Jackson wanted fresh drum sounds that would really hit. Swedien recorded them on 16-track tape as he did on Thriller, but then transferred them to digital, retaining that "fat, analog rhythm, sound" Jackson loved. Jones called it "big legs and tight skirts."

In the end, Jackson and Jones were in the studio for more than a year. "A lot of people are so used to just seeing the outcome of work," Jackson reflected. "They never see the side of the work you go through to produce the outcome." As deadlines came and passed, however, frustration mounted. Quincy Jones reportedly walked away from the project for a time when he discovered Jackson had snuck into the studio and altered some tracks. Epic executives kept pushing to wrap up the record, but Jackson couldn't bring himself to release the album until it was "ready." "A perfectionist has to take his time," he explained. "He shapes and molds and sculpts that thing until it's perfect. He can't let it go before he's satisfied; he can't."

Excerpted from MAN IN THE MUSIC: The Creative Life and Work of Michael Jackson by Joseph Vogel, by Sterling Publishing Co., Copyright © 2011 by Joseph Vogel. All rights reserved.