There are many famous tales of lovers whose romance ended in tragedy. If Romeo and Juliet is the most famous one, perhaps Sada Abe might be seen as one of the most infamous. In 1936 she killed her lover Kichio Izida, by strangling him with her belt, days after many heated love-making sessions in which the pair had repeatedly used their belts to cut off each other's breathing to intensify orgasm. After Izida's death she cut off his penis and testicles and carried them around in her handbag for three days until the police finally caught up with her. Maybe this was taking a good time just a little too far. Yet to me, as a paleontologist -- one who studies the past life of the planet -- the ultimate link between sex and death is evolution.

All life depends upon reproduction to survive, and through the passing on of genetic material, sex ensures constant evolutionary change. One question that has intrigued me is whether fossils, the remains of past life, can actually inform us about the early beginnings of sexual behavior. For a fossil to reveal that much information it must be extremely well-preserved, something that died in the prime of its reproductive life. A swift death followed by rapid burial would ensure the animal is preserved in all its glory. By a stroke of unbelievably good luck we did manage to eventually discover such a rare fossil.

In 2005 my team was searching the remote northern deserts of Australia for 380 million year old fish fossils. Working out the searing hot sun, avoiding the odd death adder in the long grass, we dutifully struck rocks with large sledge hammers hoping to reveal hidden treasures of the past. A fossil after all is an intimate record of a life once lived. The site is famous for its exceptional three-dimensional preservation of the fish skeletons and rare preservation of mineralized soft tissues, such as muscle bundles, nerve cells and even intact stomachs. That year we discovered a unique fossil fish that would lead to us redefining the nature and timing of the origins of copulatory sex in our ancient back-boned ancestors (from fishes to mammals are all 'vertebrates' after all).

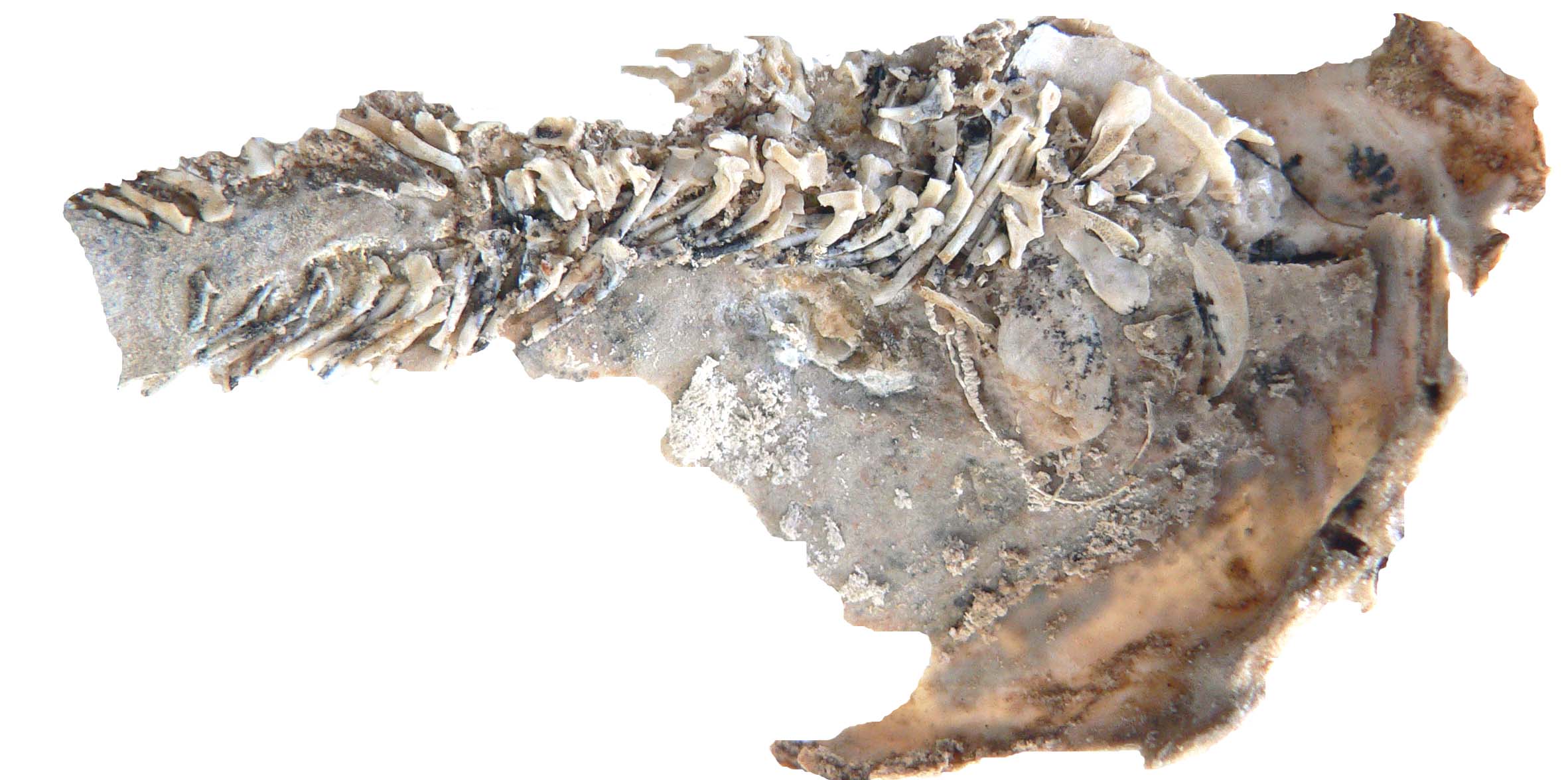

Back in my lab I prepared one such fish, a new species of bone-plated placoderms, an extinct group akin to the dinosaurs of the fish world. These sit at the very base of the evolutionary tree of all jawed vertebrates. We study them because they provide insights into the very origin of certain anatomical systems, such as when legs first appeared in our distant ancestors. Placoderms were the first vertebrates to have paired rear fins, structures that would eventually develop into the hind legs found all land animals. As the bones slowly emerged from the rocks I noticed a peculiar set of tiny bones inside the body cavity of the fish. Then, straining down my microscope, the penny dropped inside my head and I experienced one of the most sublime eureka moments of my career. I recognized the tiny bones of an unborn embryo inside the mother, still joined by a twisted fossilized umbilical cord. This discovery pushed back the fossil evidence for live birth by almost 200 million years, but more significantly meant that these ancient fishes were not just spawning in the water like salmon. They were copulating, like sharks and stingrays do today. Our discovery had just defined the oldest known act of sexual intimacy.

Placoderm embryo fish fossil

With further research we turned up fossil evidence of the oldest male sexual organs, bony claspers for passing sperm into the females, and other embryo fossils, which demonstrated that the copulatory act was much more widespread in early fish evolution than previously thought. Each of the major discoveries were published the prestigious journal Nature with ensuing world wide media coverage. Our discovery even made it in to the 2010 Guinness Book of World Records for 'oldest live birth.'

So how do ancient fish claspers relate to human sexuality? As previously mentioned placoderms were the first vertebrates to have paired rear fins and these structures formed the male reproductive organs, or 'claspers.' In essence part the skeletal structures of the leg hived off to become a pair of penises. Later in evolution after fishes left the water to invade land, all reproduction was necessitated through internal fertilization (all reptiles bird and mammals), and the need for paired male organs varied. Many birds lost the penis entirely and now use cloacal kissing to shed sperm, some completing the act in just one-tenth of a second.

The link in all this to us is through certain homeobox genes that make the reproductive organs. Hoxd13 is vital to building both limbs and genital organs in fishes and humans, so the origins of its expression can be traced back to the ancient placoderms whose early copulatory structures were simply part of the hind paired fins, the equivalent structures to our legs. When we say that 'we like to get a leg over' to have sex, for placoderms it really was 'getting a leg in.'

CGI restoration of the ancient placoderm Materpiscis giving birth to its pup 380 million years ago. Such discoveries imply they were mating by copulation (image courtesy of Museum Victoria)

Such discoveries in science raise a more overarching philosophical conundrum. How does what we observe in nature impact on human perceptions of our own sexuality? My review of sexual behavior in the animal world uncovered many cases of homosexual behavior (now documented in over 1,500 species from bedbugs to koalas), as well as bizarre cases of necrophilia, fruit bates species that practice fellatio and some that utilize male lactation, erotic cannibalism (preying mantises and certain spiders), even the the peculiar case of certain ducks using explosive penile erection (a Muscovy duck can evert its 7-inch penis at 75 miles per hour).

Some barnacles shed their penises and regrow new ones according to the changing nature of their environment. Yet despite all these references to male genitalia, perhaps the game changer in evolution is the recent discovery of sperm competition and how many females of species are taking control of sexual selection by selecting the best sperm for their offspring after several mating events. They do this through a variety of internal anatomical systems, and some scientists have suggested humans to a lesser degree utilize this as well.

All of these cases are not mere anecdotal information, but scientifically verified work published in respectable peer-reviewed journals. What nature is saying to us is clear: the vast array of human sexual behavior is not unnatural as defined by what nature does itself.