Before the matches of the 2014 FIFA World Cup began, the Brazilian people were protesting in the streets because they knew they could not afford the $13 billion it cost to host the games. In Greece, similar concerns about public mismanagement was the issue and like Brazil, street artists reflected those concerns.

Quoting a Greek artist known simply as iNO, Liz Alderman of the New York Times recently wrote: "If you want to learn about a city, look at its walls."

iNO was talking about Athens were he paints murals with a social message on buildings, but the idea of using large structures for street art, or graffiti as some call it, is not new. But is increasing in cities around the world.

Shannon Galpin, president of Mountain2Mountain, a nonprofit that creates educational opportunities for girls in Afghanistan recently wrote that: "The youth of Afghanistan are finding their voice...under the cover of night they take to the streets of Kabul, armed with stencils, spray paint and cameras."

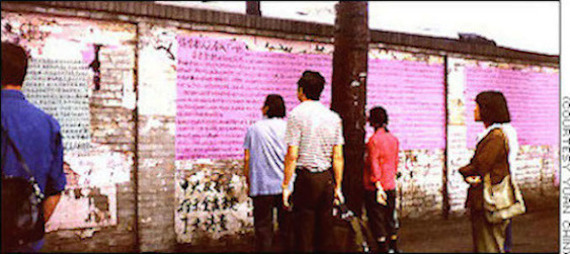

And who can forget the Berlin wall separating East from West Germany... or the so-called "Democracy Wall" in Beijing, which when it first appeared in 1978 quickly became a vehicle for expressions of dissent.

Sometimes even more.

In a few places the mural, perhaps the epitome of all street art, has been transformational. In the struggle for independence in Mexico, for example, the mural helped shape a revolution and in large part, the nexus of art and culture to the fabric of a community.

At the famed Instituto de Bellas Artes ("El Nigromante") in San Miguel de Allende, officially named the Centro Cultural Ignacio Ramirez run by the Mexican government and located in a beautiful former convent, the role of the mural as the vehicle for freedom took root.

Famed muralist David Alfaro Siquerios was by far the most politically active of the all the muralists teaching at the Instituto. He routinely had his students study the unique perspective of the art form, erase the walls which he and his and his students created, and then told them to begin anew to create a public message that both was educational and ideological.

Siquerios "painted mostly murals and other portraits of the revolution - its goals, its past, and the current oppression of the working classes. Because he was painting a story of human struggle to overcome authoritarian, capitalist rule, he painted the everyday people ideally involved in this struggle."

He believed deeply that public art was for the publics' edification.

Most cities in Mexico, surely Mexico City itself where 80 percent of the population lives, began a program of educating the Mexican people. Together with Diego Rivera and Clemente Orozco, Siqueiros used public buildings, libraries and anyplace big enough and seen enough by curious passerbys to educate and inform the community, and thus influenced the politics and the direction of the nation.

In a country that was mostly illiterate, murals were constant reminders of the validity of the struggle, and for over 20 years was the vehicle to educate a nation of its history and culture, its ancestry and purpose.

Author of the book Mexican Muralists, Desmond Rochfort, has written that the Mexican muralists transformed art to make it more accessible to the public. Their primary concern was for a "public and accessible visual dialogue with the Mexican people" representing a challenge to the commonly accepted view of the role and position of the artist in Western world. As artist advocates, they played a central role in the cultural and social life of the country.

The mural is increasingly being used, sometimes by governments, to bring messages to people. Often, as in Brazil, Athens or Kabul they are messages of grave concern or hopelessness. Often too, they are messages encouraging awareness and involvement in social matters now tearing the world apart: inequality, injustice, joblessness... issues of enormous gravity to people everywhere.