Celebrations evoking remembrance say a lot about us. We tend to use the decimal system and its major divisions to encourage reassessment in terms of looking back and connecting it to today. The 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's death seemed like a good excuse to perform his plays, though it is hard to imagine he really needed it. (I remember suggesting a concert honoring a major anniversary of Walt Disney's death when I was told by an official at the company, "We do not celebrate deaths -- only births.")

Classical music anniversaries are also significant markers of what is considered important. New York and Los Angeles ignored the centenaries of Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Bernard Herrmann, two composers whose influence is bigger than most of their contemporaries, while the 90th birthday of Pierre Boulez was the subject of much discussion and unquestioned praise. The classical music world is gearing up for the 100th birthday of Leonard Bernstein in 2018, while the New York Philharmonic is currently celebrating its 125th anniversary around Antonin Dvorak and music about New York City.

Fiftieth anniversaries are the most interesting, because people who were there at inception will inevitably survive to report, represent, and make a case for status as a "classic" for the art that emerged -- or that they created -- during early adulthood. The fiftieth of Stravinsky's Rite of Spring in 1963, and of West Side Story in 2007 are good examples.

This year we have the 50th anniversary of Star Trek. We also have a number of books that make use of oral history to take us back to the 1960s with the rise of the Black Panthers, the anti-war movement, the hippie-drug culture, the civil rights movement, and the beginnings of the women's and gay rights movements. And recently, a documentary by Ron Howard, The Beatles -- Eight Days a Week -- was released centered around the Fab Four's final concert appearance 50 years ago.

There is another important anniversary taking place at Lincoln Center that so far has gone mostly unnoticed. Fifty years ago, on September 16, 1966, 8:00 pm Eastern Daylight Savings Time, a brand new Metropolitan Opera House opened with the world premiere of Antony and Cleopatra, a 3-act epic opera by Samuel Barber, one of America's most honored and respected composers -- and with a text by William Shakespeare (who was celebrating the 350th anniversary of his death). And I was there.

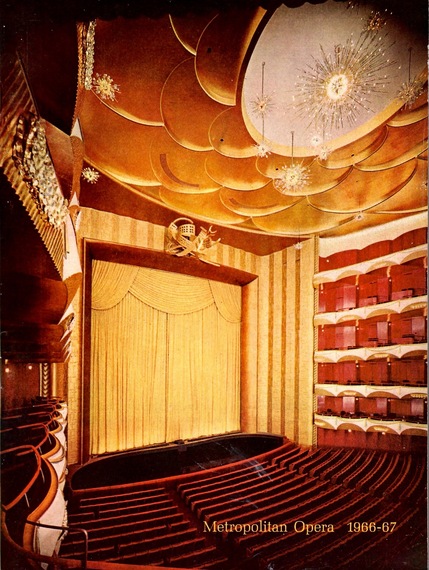

The opera house -- the largest auditorium at the slowly evolving Lincoln Center -- was bigger than the old Metropolitan Opera House on 39th street by some 500 seats. It was designed by one of New York's greatest architects: Wallace Harrison, the former director of planning for the United Nations and, as a young whippersnapper, part of the team that brought us Rockefeller Center in 1939. There could be no more admired architect for this job than Wallace Harrison.

I was 21 years old and had just moved into my senior year dormitory room in Branford College at Yale when I put on my tuxedo and boarded the New York-New Haven-and-Hartford train to New York City for the opening night. Once there, I met up with my Aunt Rose, who had first brought me to the opera when I was 16 years old. That I soon got to conduct all of its major singers -- Leontyne Price, Jess Thomas, Justino Diaz, John Macurdy, and Rosalind Elias -- makes remembering that night all the more important for me -- and the general ignorance of the anniversary all the more telling. Every one of those singers, except Jess Thomas, is alive should anyone wish to reconstruct that history from the singers' point of view.

Samuel Barber's Antony and Cleopatra was as gala an affair as could ever be imagined in those golden years of classical music in America. The composer had already won two Pulitzers, one of which was for another opera commissioned by the Metropolitan Opera, Vanessa. Along with Aaron Copland, Barber simply was American classical music. Urbane, complex, and retaining a musical language that was at once European and American, Barber was the perfect choice to open America's grandest of grand opera houses.

The Met's general director, Rudolph Bing, had spared no expense. He commissioned the world's most glamorous and effective stage director, Franco Zeffirelli, to direct and design the production -- and serve as the man to fashion Shakespeare's words into a viable libretto. (Six years earlier, Benjamin Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream also only used Shakespeare's words for its libretto.) Zeffirelli created an epic vision of Rome and Egypt, all seen through moving aluminum pipes that acted like glistening venetian blinds through which we both saw and imagined. For the last four minutes of act one, for example, the libretto says, "Cleopatra, from a great distance, slowly appears on the barge, as in a vision." And indeed, adding to the full depth of the Metropolitan's enormous state-of-the-art stage was an equally immense stage behind it that opened before our eyes as we watched a fully built ship sail toward the audience in slow motion as the curtain fell.

The costumes were a mixture of Elizabethan-meets-Cinecittà. A mere five years earlier, 20th Century Fox practically went bankrupt with its Elizabeth Taylor-Richard Burton Cleopatra. Filmed outside of Rome in the movie city created by Mussolini, Cleopatra just about ended the era of Hollywood epic blockbusters, as Sam Barber's new opera would do to American opera in the 50 years since the Met first opened its doors.

Thomas Schippers conducted. No American opera conductor had achieved the international fame of Schippers. That he was the trusted interpreter of Barber and Barber's life-partner, Gian Carlo Menotti, made him the authoritative maestro for the occasion. The libretto by Zeffirelli called for dances and ballets in the style of the Paris Opera's requirements for Verdi's Aïda. The choreography was by Alvin Ailey, making his Met debut. He worked with the Met's ballet mistress, Alicia Markova, who had begun her dancing career under the tutelage of Serge Diaghilev and was a founding principal dancer of London's Royal Ballet as well as American Ballet Theatre. And then there was the cast.

I had seen Leontyne Price make her Met debut on January 27, 1961. It was a revival of the house's old production of il Trovatore and it was a normal Friday night subscription performance. It proved to be hardly normal. Both Price and Italian tenor Franco Corelli debuted together and Irene Dalis and Robert Merrill (in astounding voice) completed the quartet of soloists. (When I had the opportunity to conduct Merrill in two arias at the end of his career and mentioned that night, he said with anger in his surprisingly inflected "New Yawk" accent, "We had casts in those days. We had casts!") When Price returned to the Met to sing Donna Anna in Don Giovanni, I made sure I was there, too. She had gone from her debut bows that were genuine and moving to something very grand indeed by the time she sang the Mozart -- I was part of her standing ovation in the orchestra section of the old opera house when Madame Price did a royal, and slightly disdainful, curtsey and the woman next to me uttered, "Well! Isn't THAT quelque chose!" Sam Barber and Leontyne Price were good friends and the composer, respecting the 19th century practice, had composed the role specifically for her magnificent voice.

With the African-American Price -- born in Laurel, Mississippi -- as Cleopatra, Rudolf Bing gave us an entirely American and multi-ethnic cast: Justino Diaz (from San Juan, Puerto Rico) was Antony, and Heldentenor Jess Thomas -- from South Dakota -- was Caesar. The first time I heard any of the music to Antony and Cleopatra it was at Bayreuth a month earlier, where Jess Thomas was singing Tannhaüser. I was being given a backstage tour by Wagner's granddaughter, Friedelind, when we passed by a rehearsal room where Thomas was being coached. I stood outside the room and listened as long as I could to get a preview of a brand new opera by a great living composer writing for the opening of my country's soon-to-be grand opera house. It was thrilling.

For those of us whose first experiences with grand opera had been the Metropolitan Opera House on 39th Street, the new house generated both excitement and dread. I first attended an opera in my freshman year in high school. The student matinee that spring was Don Giovanni, with Kim Borg in the title role and Toscanini's favorite soprano, Herva Nelli, as an alarmingly corseted Donna Anna. I was 15 years old. That Christmas I received two tickets for Madama Butterfly at which Renata Tebaldi sang the title role. The combination of the Met's chandelier and Tebaldi's high B-flat at the end of "un bel di" sealed the deal. Broadway had entered my life when I was 10 and now opera made growing up in New York a dream for a kid who liked that sort of thing.

And so, for some six formative years I attended opera at the old house -- usually with Aunt Rose. (After successfully navigating Butterfly, Rose called our house one night and said, "Johnny, I am really tired of Uncle Jim falling asleep during act two of every opera I go to. Would you like to come with me instead?" Rose had a subscription on alternating Friday nights in the dress circle. Uncle Jim, fun-loving dentist who was more interested in golf than Gounod, found the mid-winter heating system of the old house perfect for a nap. The other Friday nights were held by another Italian-American family whose daughter was my age and, well, it didn't take long for me to be going just about every Friday night.

New Yorkers have a way with making things happen. "Street smart" is a phrase for it and it applies to anything we put our minds to. For me, it meant getting tickets to the opera and to Broadway shows. The latter was harder because each show was at a different theater with a different box office with a recurring ritual involving a check and a self-addressed stamped envelope from a stranger (me) asking for "best available." When it came to My Fair Lady, for example, the wait was six months and my mother and I sat in the last row of the orchestra (which made me quite grumpy). When it came to Gypsy, my older brother and I sat on the aisle in the Broadway Theatre as Ethel Merman brushed by me to make her surprise entrance from the house shouting, "Sing out Louise!" -- and I couldn't have been happier. Sometimes I got lucky.

But the Met was different because it was the same box office each time I sent in a ticket request -- always calculated to arrive on the day tickets went on sale -- and at some point a very great and good person got to "know" me. "I am 16 years old and would like two tickets for the non-subscription Ring cycle. Thank you very much. Sincerely, John Mauceri" was both true and really effective. I got to see everything: Joan Sutherland's debut, Nilsson's first Aïda, the Bernstein-Zeffirelli Falstaff, and yes, Maria Callas' return as Tosca (with Corelli and Tito Gobbi).

Most amazing of all (now that I think of it) was the farewell gala at the old house, on April 16, 1966. Leopold Stokowski started things off with "The Entrance of the Guests" from Tannhaüser, which kept on repeating until the stage was filled with retired singers from the great early years of the last century. One after another entered to rapturous applause. (Lily Pons was the only unhappy one. "They didn't ask me to sing. I can still sing!" she was reported to have said.) When all the guests had entered and seated onstage, Stokowski did the unthinkable. He turned and spoke to us from the pit. "Please save this house with its EXCELLENT ACOUSTICS!" This did not go down well with Rudolph Bing who waited for revenge, which he nicely exacted in his book 5000 Nights at the Opera.

The old Met did not get landmark status due to the influence of New York's most powerful business men in conjunction with those who did not want a competitive opera house in Manhattan. That had been the case once before with Hammerstein's Manhattan Opera House and the Met had won. The Met was not about to compete with itself in 1966. And after much handwringing, the great auditorium was demolished in 1967. RCA bought the gold curtain and cut it into little squares that were sold in a box set of long playing records, called "Opening Nights at the Met." Parts of the proscenium were prize objects for collectors. I once had cocktails at the president of New York's Wagner Society and was horrified to see that the glass-topped coffee table on which I rested my chardonnay was a section of the old arch that had Wagner's name on it and that had once proudly stood above the great stage from 1883 until the wrecking ball turned it into, as I said, a coffee table.

And so, with all that history, how were we supposed to greet this new opera house

on that early fall evening in 1966?

PART TWO WILL ANSWER THAT QUESTION.