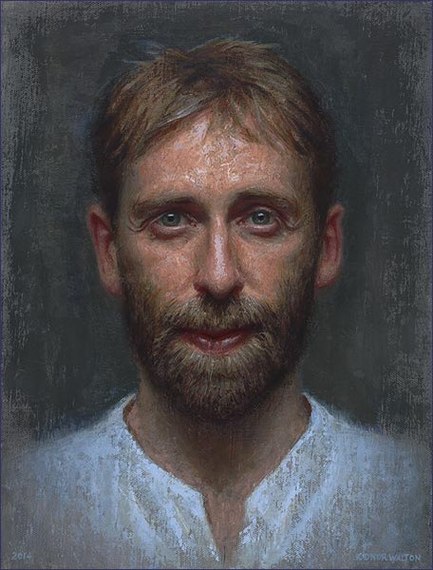

Conor Walton, Self-Portrait, 2014, Oil on linen, 16 x 12 inches

Conor Walton, one of Ireland's leading representational painters, strives to create paintings that go beyond mere technical competence. One of his stated goals is to endow his works with high, shared ideals so that his images will carry some of the cultural importance that religious art carried in earlier eras.

I recently interviewed Walton, who will be exhibiting eight recent still life paintings in San Francisco this month, and asked him about his background, ideas and interests.

John Seed in Conversation with Conor Walton

Veiled, Oil on linen, 18 x 20 inches

Tell me a bit about your childhood: were you always an artist?

No! I was an astronaut, a commando and a zoologist first, as far as I remember. But I always drew pictures. I probably spent most of my childhood lying on the floor drawing and painting. I was quite shy and a bit of a loner. Drawing allowed me to escape into a world of my own making. But it was also my primary means of relating to the real world. I built my world out of pictures.

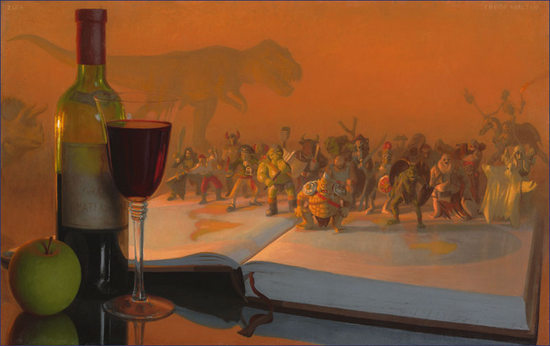

Saturnalia, Oil on Panel, 18 x 24 inches

Was Ireland a good place to receive artistic training? Tell me about your studies in Ireland and also in Italy.

The Ireland I grew up in was still a very traditional, conservative, Catholic country. It was largely untouched by the destruction and upheavals of the two World Wars that completely changed the cultural landscape in the rest of Europe. The teaching in the art colleges was very conservative up until the late sixties, when there was a sort of Cultural Revolution and the Modernists burst in and started shaking things up. As a result, when I went to NCAD in 1989, there were still some 'Ancien Regime' teachers left who were trying to teach painting as a craft according to "academic" principles.

But there were also Abstractionists, Neo-Expressionists, Pop Artists, Postmodernists and Conceptualists. All the major strands of twentieth-century art were represented by the teaching staff when I was there. They all seemed to secretly despise each other, and disagreed in their teaching about absolutely everything, and I found the whole experience extremely disorientating, but I think I learned a lot, from all of them in different ways. In terms of the cultural power-politics of the time, the 'academics' and 'traditionalists' were a waning force, but they were still there. They are gone now.

My time in Italy was in many ways the opposite experience. When I studied painting in Dublin, my interest in the craft and tradition of painting was seen as deeply reactionary. I was denounced for painting 'salon pictures', for producing a sort of wanna-be authoritarian or fascist art. But when I went to study with Charles Cecil in Florence, I was made to feel like an apostate of tradition - a Modernist! A Relativist! Charles avowedly hated the Twentieth Century, and his teaching seemed designed to produce a sort of simulacrum of the art of an earlier age, in which all evidence of Modernity, of NOW, was to be ruthlessly repressed.

I thought this was utterly pointless, and I ended up having as many arguments with Charles as I had with the Modernists back in Dublin. In fact they were even more bitter. I was almost banned from Charles' studio. The only thing that kept me in was that I knew my art history. Charles had a great way of quoting Leonardo, or Rubens, or Joshua Reynolds, like they were still alive and he'd just been talking with them over a drink in the bar next door. I'd studied all the sources he was quoting, and could answer back, and even correct him occasionally. Even while this annoyed him and challenged him, it thrilled him. No-one else answered Charles back. So he never kicked me out. And I did learn a lot from him, though not always what he wanted to teach me. I even respect the depth of his hatred for Modernity. I've absorbed it in my own way.

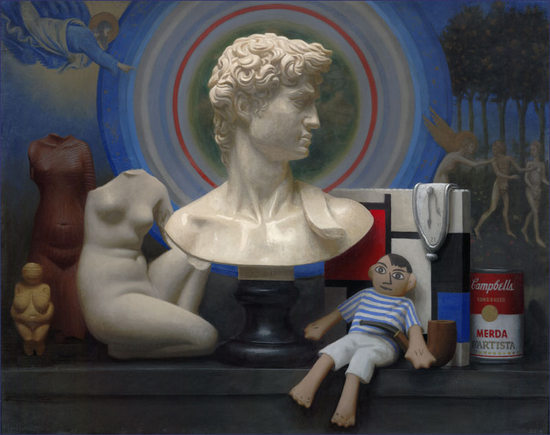

Ceci n'est pas une Blague, Oil on linen, 24 x 30 inches

You have a degree in Art History: when did you make the switch and make painting your main priority?

Painting was always my main priority. But NCAD ran a joint honours degree in art history, and those with brains to spare were encouraged to sign up and get two degrees for the price of one. At the time, hardly anyone in Ireland was making a living from art; you were expected to support yourself principally by teaching when you left college. Because my work aroused the hostility of the Modernists I was constantly in danger of crashing out of the painting department, and I couldn't see myself getting a teaching position there in the face of such opposition, so teaching art history seemed like a reasonable alternative. I was even allowed to write my thesis on abstract art and received a prize for it, despite my saying things in the thesis that were highly critical of the whole notion of abstract art. It seemed to me that art history was still a true 'academic' discipline with objective standards, whereas in the painting department any notion of academic discipline and objectivity had collapsed. But the art history department in my art college was unusually liberal.

When I went on to do a masters in art history in England intending, again, to focus on Modernist art from a highly critical perspective, I found my path blocked. I found that the specialists in Modernism I sought out to supervise my thesis wouldn't even entertain my ideas and refused to cooperate. Their hostility showed me that art history isn't such an objective discipline after all!

The Enemies of Progress, Oil on linen, 24 x 48 inches

Basically, those who make their academic careers out of studying an artist or movement become cheerleaders for their subject. They can become so wedded to the values and narrative on which the high reputation of their subject depends that they won't see them challenged. This is why the broad history of art in the twentieth century has become such a conventional, well-established orthodoxy. So I ended up doing my thesis on an episode in seventeenth-century cultural politics called "The Battle of the Ancients and the Moderns". I was still attacking the precepts of Modernism, but this time from behind! Which was fine. My supervisor said it was one of the best dissertations in the history of the department, and I was awarded my degree with Distinction.

In the end I found I didn't need to teach art history; I could earn a living from painting. But I owe a great deal to those studies. A grasp of past styles, iconography, symbolism has enriched my work in pretty obvious ways. But the drive behind my inquiry was my sense of cultural disorientation. Why did I feel so at odds with the ideas that were being taught at art college? Why did I find it so hard to admire or even respect so much contemporary art? These were puzzles that I could only solve by a period of intense study and deep reflection. And this was what I achieved while (supposedly) studying art history. So I managed to reorientate myself, and my world-view gained depth and maturity.

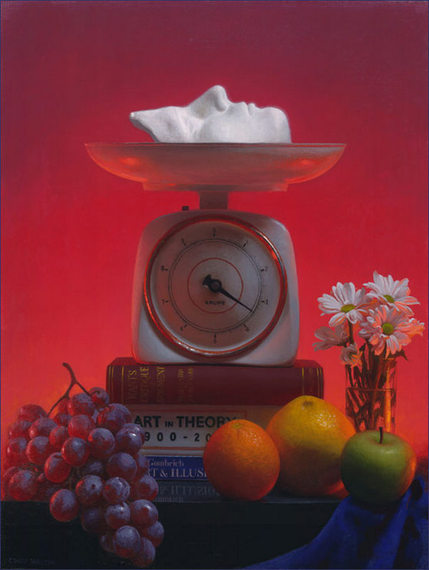

Still Life with Judgement, Oil on linen 24 x 18 inches

You have a feeling for allegory. Tell me about one of your allegorical paintings.

My Still life with Judgement is an allegory of aesthetic judgement. Modern notions of aesthetic judgement are derived from Immanuel Kant, whose Critique of Judgement is one of the books in the painting. The basic idea is that Art affords us an extremely pure pleasure, unmixed by any self-interest, because Art is useless. Now this idea is total crap. Art is extremely useful. Those who make a big deal about it demonstrate their refinement, their class and (if they have it) their wealth for all to see. It has huge social and cultural utility. But all these vested interests hide behind the common lie that, in matters of Art, good judgement is disinterested. And in this painting I've tried to make an image that articulates some of my feelings about the subject.

The old Krups weighing scales performs two functions in the painting. With a cast of a human face atop, it becomes a metaphor for the coldly calculating brain behind the face -- backed up by books of art theory, history and criticism -- weighing, measuring, judging 'disinterestedly'. The face is turned resolutely away from the earth and the fruity pleasures at the base, contemplating 'higher' things. But the face on the scales also invokes the symbolism of the Last Judgement and Weighing of Souls. So maybe the 'disinterested' aesthetic judge is also up for judgement. These echoes of Christian iconography also help to amplify the religious, apocalyptic feel of the picture, making it akin to a sacrificial alter or shrine. The fruit at the base are a sort of natural, earthy counterpoint to the strange, artificial construction above. Painted with the brightest, purest colours and most alluring textures I can muster, I want the whole picture to appeal to your sense of touch, to your appetites, to your fascination with illusions, to your covetousness, to every pleasure which is physical, earthy and NOT disinterested.

Overall, I hope the painting maintains a sort of equilibrium between the elements. Although I intend my paintings to honour Nature and appeal frankly to the senses, to pleasure and passion, in my demand for rigorous formal order and intellectual content, I know I'm also inside this painting's coolly calculating intellect.

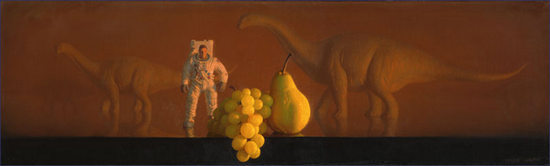

Fat Tails, Oil on linen, 15 x 36 inches

What is it about the still life genre that interests you ?

To begin with I was not really interested in the genre: my principal interest has always been painting people and 'living nature' rather than 'nature mort', but live models are expensive and I paint slowly, and still life seemed like a good way of producing small saleable works that I could paint from life and develop my eye and technique at the same time. But the deadness of objects, their lack of energy or any psychological presence has always been an obstacle to me, something to overcome. I'm not at all happy with still life as an exercise in pure objectivity or pure form. So I end up trying to treat the painting as a miniature drama, a microcosm. I use objects that have meaning for me and try to get the whole painting to make a statement, to express an attitude. And because still life is an art of objects -- of deadness -- attitudes like objectivity, materialism, fatalism, nihilism, are easily accessible through the genre. It's a battleground for me: a way of waging small-scale war against modernity.

Illusionism still has great artistic potential because reality is still something we find difficult and threatening. I've heard it said that people can avoid facing reality, but they can't avoid the consequences of not facing reality. I think my work is very much bound up with these issues; with naturalism at one remove, with fantasy and disillusionment. In our culture, to an historically unprecedented extent, affluence and industrial might have become weapons in a general war against reality, against nature. But Nature's still going to win.

I suppose fundamentally I think of myself as at odds with the still life genre and most of its 'default settings'. But in some ways it's a good position to be in: everything I do in still life is done tactically, strategically, self-consciously; my dissatisfaction with and to some extent contempt for the genre is what allows me to push it around, to use it purely as a means to my ends. Every once-in-a-while I get very frustrated with painting objects and feel like I'm close to exhausting its possibilities for me, but it usually doesn't last long. Right now I'm flying along. It's a great time to be a cultural pessimist!

Here be Monsters, Oil on Linen, 15 x 24 inches

What will be showing in San Francisco?

I'll have about eight paintings in a still-life exhibition at CK Contemporary along with eight really brilliant painters from right around the world: Jay Mercado, David de Biasio, Dianne Gall, Hollis Dunlap, K Henderson, Ottorino de Lucchi, James Neil Hollingsworth and José Basso.

You can see an online catalogue of the exhibition here.

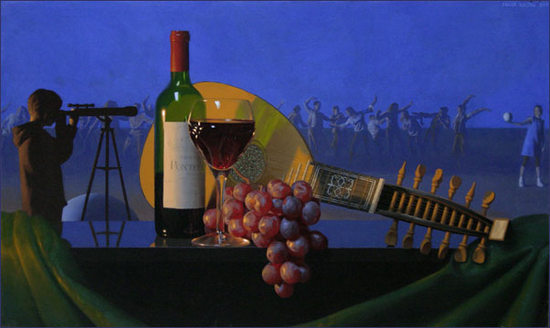

Earth-Moon Distance, Oil on linen, 18 x 30 inches

What are your interests outside of art?

Any chance I get -- which is not too often these days -- I try to get some time in the wilderness, in something approximating Nature. I'm lucky to be living beside the sea, with long cliff walks nearby, and near the Wicklow mountains, where you can go off-track and not meet another soul for a day if you want to.

I like to read. I'm interested in philosophy and history and science. More recently, in order to fathom how our crazy world really works, I've taken to reading books on economics and scanning the financial papers.

But these days, raising my three young children is my main interest when I'm not painting. My eldest beats me at chess now, so things are getting very interesting indeed!

OBJECTS OF BEAUTY

Contemporary Still Life Painting

Opening Reception: September 6, 6-9 PM

CK Contemporary

357 Geary Street

San Francisco, CA