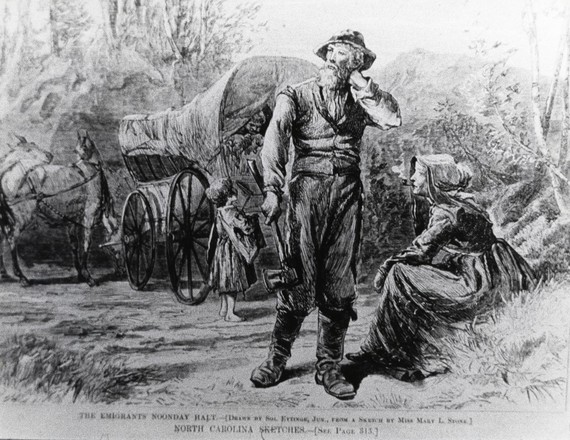

Image courtesy of digitalheritage.org

October 1717: Philadelphia is a bustling town and busy port with immigrants arriving regularly. Quaker Jonathan Dickinson notices a new type of immigrant in the New World, "strangers to our laws and customs, and even to our language," observes Dickinson. The young women dress in scandalous fashion, bare legged with tight blouses accentuating their form. Older women wear ankle-length dresses and full bonnets. The men are tall and lanky, wearing felt hats and loose-fitting shirts. The newcomers speak English with a strange cadence out of place and out of tune with Pennsylvanian English. They look poor but, heads held high, carry themselves with dignity and defensiveness. They've got a chip on their shoulder. These were the first Scots-Irish immigrants in America, ancestors of many American citizens and a heavy influence on culture throughout the nation.

What we see today in the form of camouflage hats, bearded male faces, Daisy Duke shorts and 4x4 trucks began on the cool misty British Isles, the northernmost sections of England, northeastern Ireland and western Scotland to be precise. The chapter, "Borderlands to the Backcountry" in David Hackett Fischer's book, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, discusses these people in exhaustive detail. The book is a cultural anthropologist's guide to sorting through tangles of British immigrants and cultures in America. Though not his clear intent, Fischer's book is also a modern day taxonomic field guide to those cultures, bushwhacking a trail from modern cultural characteristics to specific groups of immigrants and even back to the British Isles.

The Scots-Irish were country dwellers, but historians disagree about the dominant economic class. A few were of the gentry class, a group that would later play important roles in the shaping and governance of the future United States. Andrew Jackson -- practical, fearsome, often cruel but a man of the people -- is the archetype of this group. Many historians claim the majority of Scots-Irish were poor with one writer, not referenced by name in Fischer's book, describing them as "the scum of two nations." Other historians believe the majority were independent farmers, neither wealthy nor poor, but people who had forged some degree of independence from powerful landlords that governed most British Isle soil. Whether moderately wealthy, dirt poor, or somewhere in the middle, one thing was certain -- the Scots-Irish were defiant in the face of authority and fiercely proud. As Fischer writes, "their pride was a source of irritation to their English neighbors, who could not understand what they had to feel proud about."

Pride is complicated emotion. What other sentiment is listed among the seven deadly sins while also applauded during acceptance speeches? Wait, don't answer that. But still, pride is a complex feeling and sources of pride are sometimes difficult to trace. Without reading Webster's take, I had always thought a sense of pride needed attachment to accomplishment. I say this as a descendent and member of Scots-Irish culture.

Though the blood of many other peoples flow through my veins, the dominant culture of my birth place and current residence is decidedly Scots-Irish. As the son of an Ozarkian -- with moonshine running, bootlegging relatives and the whole bit -- growing up in rural western Arkansas, no one in my family on either side ever had much money. I grew up lower middle-class in a small town full of folks mostly the same. There are no titans of industry or politicians beyond the local in my bloodlines. Yet we were always proud of who we were. Personal pride came from my lineage. I was proud to be the son of Johnny Sr. and Linda Kay, grandson of Devoe and Lois Sain, and John Willis and Bertia Payton. Between those six people immediately preceding me in the bloodline are zero college degrees, no political power and very little money. But they were all "good people" in the community -- hard workers, helpful neighbors and solid if not spectacular citizens. There was family honor and pride in that. And even now, as a relatively cool headed middle-aged man, woe to the person disrespecting my family or its good name. I take it personally. Only recently did I ask myself why. Pride is a dichotomous emotion. One form, also known as hubris, is an inflated ego and delusions of grandeur. The other form, though still an inwardly directed emotion, is a sense of satisfaction and contentment in who you are as a person and even as a culture.

I've been studying the history of the Scots-Irish for a couple of years now, and pride was always a defining characteristic of the culture. Claims of innate pride aside, nurture is the obvious culprit. Contrary to country songs, T-shirts, ball caps and even geography, no one is born Scots-Irish, country, hillbilly, redneck or even Southern by the grace of God. It's a learned condition. It's a direct product of your rearing.

Discussions over that polarizing rebel flag were the catalyst for my most recent readings of Albion's Seed and current pondering about pride. I've been digging through the text searching for the source, the germination of pride in a culture calling for recognition today with a rebel yell directed toward the rest of the country and the world. My thoughts on the flag run counter to the majority here in deep-red western Arkansas. I have no illusions about what it stands for. From it's first incarnation as "the white man's flag" as it was called by designer, William T. Thompson, to its service as the symbol of choice for so many white supremacy groups today, the message is clear. The banner of people claiming superiority over another people deserves no reverence or honor. Interestingly, Confederate flags are more popular in western Arkansas today than they were during the Civil War when the region was split between Union and Confederate volunteers and sympathizers. Western Arkansas was far from unified in its allegiance to either side. This makes the current wave of rebel pride a bit puzzling.

Or does it.

Western Arkansas, specifically the mountainous regions, have long been home to folks that want to be left alone. Independence is the common thread, independence from government and independence from the market. Early Ozark homesteaders were subsistence farmers. Consumer economies mere whispers of an idea from far away parts of the country. Almost everything was hand to mouth with only a portion of summer corn as the exception. Those ears of corn, in fermented liquid form, constituted the earliest cash crop for Ozark inhabitants because it made life on a hardscrabble farm a bit more endurable and you couldn't pay property taxes with salt pork.

This existence was common throughout rural areas of the country, particularly the Southern highlands and swamps, the marginal lands settled by people from Ulster, the Scottish highlands and border regions of Britain that made their way to Philadelphia in late summer and autumn of 1717. From there, they took to the hills of Pennsylvania, down through Appalachia and eventually into the central highlands of Missouri and Arkansas before reaching into western territories. The culture accompanying them spread beyond the hills and poured over the backwoods and backwater of frontier and agrarian regions across America. It soaked the rural South -- those Southerners too poor for ownership of plantations and slaves -- to the bone. It was the culture of a people that always seemed to settle in the wildest and poorest lands, taming the wilderness, surviving by wits and will and owning a suspicion of those in power forged from centuries of standing against various landlords and crowns. They stood tall, though often in homespun clothing, with fierce pride smoldering in their eyes. It was and is a warrior culture.

What we see today from flag waving, cap wearing, pickup driving folks is not Southern. It's rural. It is country as sausage gravy and cathead biscuits, barbwire and dirt roads. It's a rural lineage stretching across the centuries and across the Atlantic. The swell of pride that to the outsider seems misplaced is the result of a culture that has always done things the hard way. It's a culture hidden by myths of ignorance and cartoonish portrayals, but a culture that bred some of the finest woodsmen, soldiers and leaders the world has ever known. The Quaker portrayal of the Scots-Irish as poor overall was inaccurate. Rough around the edges is a better description. It was a rugged character later expressed in leaders from Confederate General Stonewall Jackson to President Theodore Roosevelt.

Of course racism constitutes some appeal of the flag to some of its supporters, but many cries for recognition of heritage are sincere in their claims. For the majority of Southerners today, the Confederate battle flag has absolutely nothing to do with hate. It is about pride in ancestors overcoming obstacle after obstacle with little fanfare, living solid if not spectacular lives in support of community and family.

The history behind that star covered Southern cross distorts the cries of pride not prejudice. The culture draped itself in an evil symbol and that has led to the identity crisis you see today. Blame selective history teachings and a yearning for acknowledgment. For most us, it is not a culture of racism and treason. But it is a culture sorely in need of a better symbol.