Jump Rhythm Jazz Project, the blissfully original dance company that Billy Siegenfeld founded 22 years ago in New York City is on stage this weekend. A Jump Rhythm performance is definitely a dance concert, but if you know ballet, or if you know any of the four hundred shades of modern and contemporary, in fact even if you know jazz, you might not be entirely ready for a Jump Rhythm concert. These shows are different. Despite the rich, riveting movement design, this is different from the ground up.

Jump Rhythm Jazz Project, the blissfully original dance company that Billy Siegenfeld founded 22 years ago in New York City is on stage this weekend. A Jump Rhythm performance is definitely a dance concert, but if you know ballet, or if you know any of the four hundred shades of modern and contemporary, in fact even if you know jazz, you might not be entirely ready for a Jump Rhythm concert. These shows are different. Despite the rich, riveting movement design, this is different from the ground up.

For one thing, it's nothing like any of the you're-the-audience-here's-the-show concerts that we all go to. Jump Rhythm Technique, a "vocally accompanied system of dance and theater-movement training" created by Siegenfeld, is firmly rooted in the more engaged traditions of the arts that Siegenfeld calls 'American Rhythm Dancing.' "I love stripped-to-the-bone jazz-rhythm-driven, blues-rhythm-driven, and funk-rhythm-driven music and movement," Siegenfeld says, "because it's all built around the heightened conversation of call and response." It's an inclusive heritage created in large measure by the victims and casualties of exclusion, and it embraces constant communication, only some of it verbal, among performers, and between performer and audience.

That's not all. This isn't at all like ballet, or even like the contemporary forms that expand on the classical world's principles of balance and posture, where the intent, primarily visual, is to create an impression of elevation, even of transcendence. In Jump Rhythm (which is actually a registered trademark), balance is based on what Siegenfeld calls "being down," it's a stability that can be so rhythmic and hypnotic that it can look like it defies gravity, but in reality, it never even tries to. This is a different kind of balance, and 'Down' is the one thing it never forgets.

In his brightly imaginative Why Gershwin?, Siegenfeld and Jump Rhythm duet partner Jordan Batta move precisely, gracefully, and energetically in a continuous flow of balance, both in their movement and in the interaction between the roles they portray. It's a rhythmic movement conversation that resonates Astaire, but since the score is James Brown as well as Gershwin, it's as deep as the street. Maybe deeper, because in Billy Siegenfeld's Jump Rhythm, everything is down. "Downwardness leads to inwardness," Siegenfeld emphasizes. "The downwardness is a physical thing, but the inwardness is spiritual." It's a constant, complex, deeply rooted equilibrium, a dynamic harmony between individuals, and of an individual with the reality of the physical world. It's a celebration of movement, of rhythm, of balance.

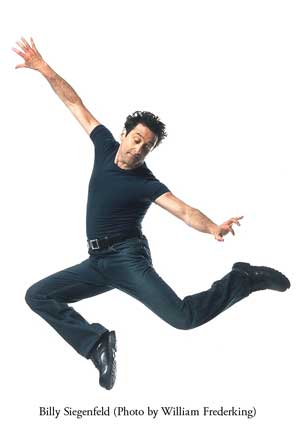

Balance is something that Billy Siegenfeld knows inside out. In his Jump Rhythm Technique, and in the vividly entertaining art of Jump Rhythm Jazz Project, he explores where balance comes from and what it's made of, where to find it and how to use it. He's a performing member of Jump Rhythm Jazz Project, and he moves easily and energetically through choreography as intricate as any, but that's just the beginning of Billy Siegenfeld's understanding of balance. He knows it inside out.

Siegenfeld is the artistic director of Jump Rhythm Jazz Project, as well as its principal choreographer. Not only does Jump Rhythm Jazz Project perform extensively, the company members are also enthusiastic teachers of Siegenfeld's Jump Rhythm Technique; they teach it at schools and community centers throughout the Chicago area where they are now based, and at universities around the world. That's a lot of different moving parts to keep in balance, but there's still some more.

Siegenfeld's work at Northwestern University, where he's been a professor since 1993, includes extensive writing on the subjects of rhythm-generated dance and movement; he publishes eloquent, academically significant articles like Performing Energy: American Rhythm Dancing and "The Great Articulation of the Inarticulate". It wouldn't be all that inaccurate to say that he's "more than a dancer," except that when it comes to balancing this much motion, there's probably no such thing as being "more than" a dancer.

When Siegenfeld is dancing, he's moving in a tradition that comes from way back, often from people who didn't read or write, but who could express themselves, and converse with one another rhythmically, in ways the word-bound world of formal dance theory rarely even dreams of. When Siegenfeld is writing, he's working in a tradition that requires clear verbal thought, and when necessary, convincing argument. Staying real where the things that matter most are what you feel, and then being able to discuss it with people who've never been to that part of the world isn't just a balancing act, it's like dancing on a tightrope. Siegenfeld keeps it all in balance though; in such a rhythm-rich world, you're always down.

When Siegenfeld is dancing, he's moving in a tradition that comes from way back, often from people who didn't read or write, but who could express themselves, and converse with one another rhythmically, in ways the word-bound world of formal dance theory rarely even dreams of. When Siegenfeld is writing, he's working in a tradition that requires clear verbal thought, and when necessary, convincing argument. Staying real where the things that matter most are what you feel, and then being able to discuss it with people who've never been to that part of the world isn't just a balancing act, it's like dancing on a tightrope. Siegenfeld keeps it all in balance though; in such a rhythm-rich world, you're always down.

"We call it Jump Rhythm. The forward-moving energy of it is built around a core of calm because your feet and body weight are always dropping downward into the floor," Siegenfeld explains. "Once you let the body give in, you can move freely." It's an earthbound understanding of freedom in motion, based on movement awareness handed down from century to century in a remote African past, where uncountable natural wonder was everywhere. It's the heritage of self-expression in rhythm, and in the rainbow of spaces inside of rhythm, from a bitter past where it was often the only defiant victory possible for those who were denied any right to express themselves. It's a different way to move, to move freely, and to move toward freedom. "All of a sudden, you're liberated into 'flow'," is how Siegenfeld describes it. "I mean true flow, capital "F" flow. That's what makes the cheetah move so fast. That's why Astaire looks like he's flying -- it's because he's down."

This article first appeared at 4dancers.org