Image credit: Davide Bonazzi

Are women better than men at investing? According to one robot, the simple answer is "yes."

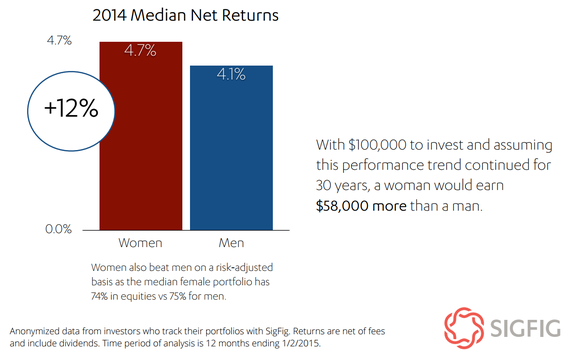

That robot is Sigfig, a robo-investment advisor whose study of gender and investing recently reached that conlcusion.

The study's sample consisted only of Sigfig customers, and I wonder whether men and women would be equally attracted to a robo-investment advisor. But let's pave the way for a focused discussion -- let's assume that the study's sample is representative, and let's stipulate its conclusion: women are better investors than men...at least, in 2014 they were.

But why? The report gives several reasons.

1. Men were 25 percent more likely than women to lose money in the market.

If you want to get rich, more important than making money is not losing it. Whether you study experts' advice or the methods that made them famously rich, you can't miss this point.

- Money expert Tony Robbins calls this his # 1 Core Principle.

- Warren Buffett, describing his own investing method, calls it his "margin of safety."

The margin of safety kept Buffett from losing money (most of the time). How? Simple. Buffett would look for companies priced lower than the value of their assets. This way, if the company began to crumble, he knew he could liquidate the assets to regain his invested principle.

It's interesting to note that the margin of safety rule is also why Buffett always declined to invest in technology companies, because their assets were not worth more dead than alive. Buffett endured much ridicule from technologists -- both investors and founders -- for this policy. He missed out on some of the highest-return investments in our lifetime, all technology plays. But he also avoided the catastrophic losses that followed the euphoria those "unicorns" encouraged, as in during the dot-com bust. Ironically, Bill Gates was one of Buffett's closest friends through it all, which serves to reinforce the point: more important than the potential for massive payoffs, and more important even than the niceties of friendship, do what you can to not lose money.

Why were women in this study less likely to lose money? The second and third reason speak to that.

2. Men churn their portfolios 50 percent more than women.

Transaction costs kill. Every trade you make, if you're paying transaction fees, means that you're starting with less principle on day 1 of your new investment than you had on the last day of your previous investment. This is one reason many experts advise investing for the long-term.

Does it have to do with sex? According to psychologist Christopher Ryan (who is not an investing expert), the answer might be yes:

Men, especially, are designed by evolution to be attracted to sexual novelty and to gradually lose sexual attraction to the same partner in the absence of such novelty. The so-called Coolidge Effect is well demonstrated in social mammals of all sorts, and is old news to anyone knowledgeable about reproductive biology.

The Coolidge Effect says that mammals -- especially males -- are attracted to novelty. While the effect has most often been studied in a sexual context, it might also have some relevance to why men trade investments more than women.

Think about what this could mean when an investor perceives that an investment is approaching a dip in value. There would be a confluence of compulsions at play.

- The investor might think, "well I know I should buy low and sell high and therefore resist the urge to sell in advance of minor dips."

- He might also think, "based on my study of some of the investing greats, I really should be in this for the long-term -- and therefore resist the urge to jump from one temporary peak to another."

- But the investor might see a trend of other investors dumping the investment.

Combine all of that with the (apparent) innate, male urge for novelty, and we might say that women investors are more likely to have the balls of steel necessary to stay put.

On resisting the bandwagon's siren call, Ben Graham, Warren Buffet's investing mentor (and reportedly not a woman), famously said: "when people are greedy, be fearful; and when people are fearful, be greedy." Since most investing markets spend more time rising in perceived value (thus, the cycle of bubbles), this suggests that the right thing to do, most of the time, is to stay put. In investing, you want to be greedy long-term, not greedy short-term.

3. Men were 1.5x more confident that they would beat the market in 2015.

This difference in confidence between men and women is actually consistent in many areas beyond investing. Women tend to be less confident than men, but the statistics suggest this has nothing to do with actual competence. By all accounts, women seem to be thriving better than men. Katty Kay and Claire Shipman write:

We've made undeniable progress. In the United States, women now earn more college and graduate degrees than men do. We make up half the workforce, and we are closing the gap in middle management. Half a dozen global studies, conducted by the likes of Goldman Sachs and Columbia University, have found that companies employing women in large numbers outperform their competitors on every measure of profitability. Our competence has never been more obvious. Those who closely follow society's shifting values see the world moving in a female direction.

The irony of this so-called confidence gap is that, while debilitating in most areas of life, it's actually a good thing for investing. Why? Because the performance of an investment is not something a mere shareholder can typically control (unless he/she is also an operator or manager of the business issuing the investment).

Whereas confidence and overconfidence can actually lead to better outcomes through better performance, the operative question is whether the chest-beater actually has any influence on performance or not. Most investors do not. That, combined with the fact that most confidence in general is not based in fact (for example: 90 percent of American drivers believe that they are above-average drivers...hmmm), less confidence in investing seems to be a good predictor of relative investor success.

The Takeaway

If you want to be a good investor, you could learn to worry more and excite less, or you could just be a woman from the start.

Note: this article was originally published in Fredo Pareto.