Like countless Americans this Memorial Day weekend, I am thankful for the brave and courageous men and women of the military who died while serving the United States.

And as an undocumented immigrant who was born in the Philippines but grew up in the United States, I think of the shared history between the two countries. During the Spanish-American War, many Filipino soldiers died while fighting with the Americans against Spanish rule, only to later fight the Americans who wanted to seize control of the Philippines. I also think of the more than 250,000 Filipino soldiers who volunteered to join the U.S. military and fight with the Americans during World War II, when the Philippines was a U.S. commonwealth. (Some 60 years after failing to honor its promise to pay Filipino soldiers, the U.S. finally paid the veterans, many of them naturalized American citizens. Many of the soldiers have died.)

And this holiday weekend, I think of the Filipino-American service men and women who risked their lives -- and are risking their lives -- to serve our country.

Like my uncle, Conrad Salinas.

Born in Iba, Zambales, a province of rice paddies and endless beaches in the Philippines, Uncle Conrad's parents expected him to be a farmer or fisherman. But he wanted something more for himself and his family. So he found his way to the U.S. Naval Base in Olongapo City and joined the U.S. Navy, arriving in the United States in 1977. He became an American citizen in 1981 -- the year I was born. For about 30 years, as he petitioned his parents and seven siblings to come to the U.S., he's built a life with his family in the San Diego area, just a few miles drive from the U.S.-Mexico border. Uncle Conrad served in the United States Navy for 20 years and retired as a lieutenant. His retirement party was a big deal for the whole family, including my grandparents, my Lolo (grandpa) and Lola (grandma), who treated Uncle Conrad as if he were their own son. (Uncle Conrad is the son of my Lolo's brother.)

My extended family, all naturalized American citizens, are among the 17 million people in the U.S. living in mixed-status immigrant households where at least one person is undocumented. Out of many uncles, aunts and cousins, I'm the only one in my family who doesn't have the right papers to be in the U.S. (About 4.5 million American-born children have at least one undocumented parent.)

Early last year, when I was asked to appear in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee, my family flew to Washington, D.C. They sat behind me as I testified, along with my high school mentors. Uncle Conrad is so proud of his service in the U.S. Navy that, unbeknownst to me, he brought his dress uniform and wore it during the hearing.

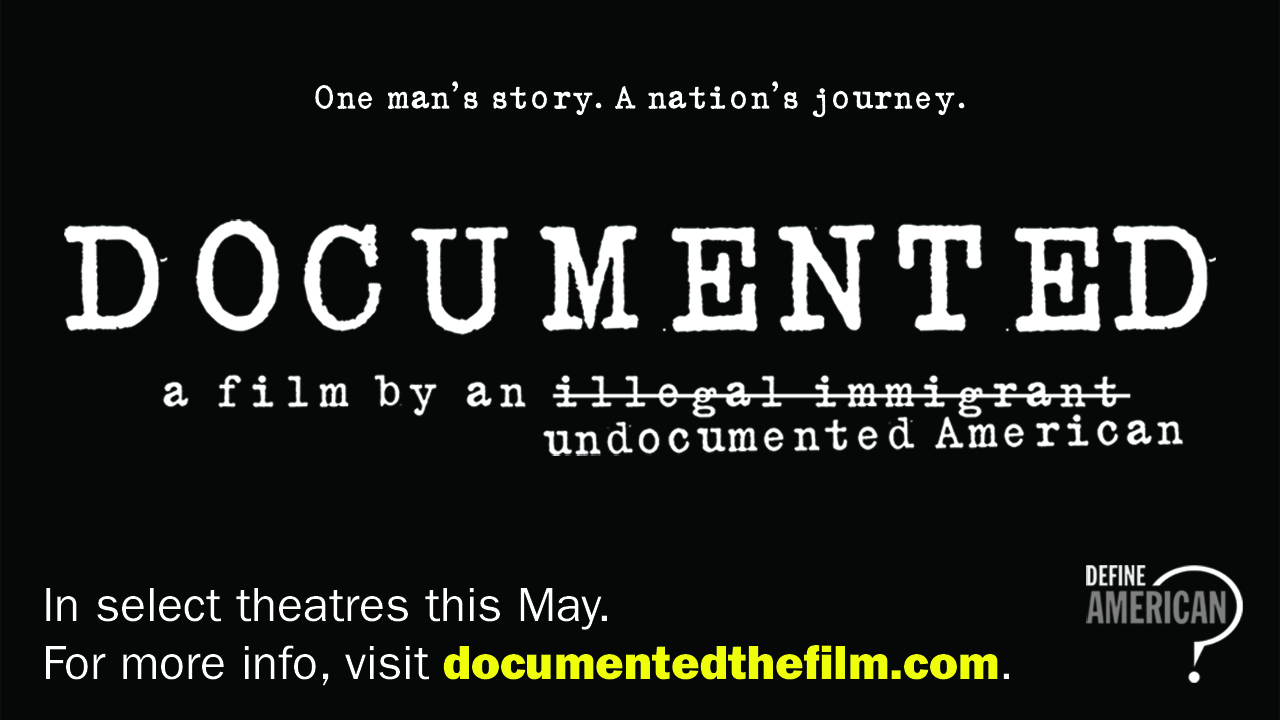

In this clip from my film Documented, I prepare for the Senate hearing while Uncle Conrad defines "American." This, to me, is a fitting clip to share on Memorial Day weekend, given the continued contributions of immigrant families to an all-volunteer U.S. military, and, if a bill called the Enlist Act is passed, given the possible contributions of young undocumented immigrants who want to serve the country they call their home.

'Documented' is in theaters, playing in San Diego from May 23 to May 29; in Seattle and Washington, D.C. from May 30 to June 5; in Miami from June 5 to June 8; in Chicago from June 13 to 19; and in Denver from June 20 to 26. Find tickets and showtimes here.