Test of Iranian Shahab 3 Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile

The Associated Press recently revealed the existence of a secret agreement that would allow Iran to restore "its full uranium enrichment capacity," utilizing more advanced, faster centrifuges, on the 10th anniversary of signing the nuclear agreement. The leak, from the International Atomic Energy Agency, the organization charged with monitoring Iranian compliance with the nuclear accord, has led a number of intelligence agencies to again issue warnings that it "was highly likely" that Tehran will have a nuclear weapon capability within the next 10 to 15 years. Not surprisingly, the news generated renewed anxiety in the Persian Gulf about Iran's intentions in the region.

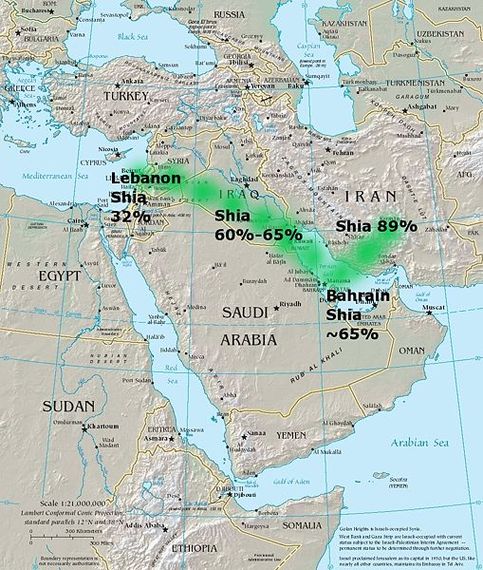

The rise of Tehran's power in the Middle East has often been conceptualized as an Iranian "arc of influence," which stretches across Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Gaza. There is also, potentially, a second such arc based on the large Shiite populations along the southern and eastern rim of the Arabian Peninsula. To date, however, the Sunni governments in the Gulf have, for the most part, been able to keep a lid on Shia dissent, and on Tehran's attempts to mobilize those Shia communities, although they did intervene in Yemen to block Tehran backed proxies from seizing control. The prospect of a nuclear armed Iran and the steady expansion of Tehran's influence, however, has underscored the fact that Middle East politics are increasingly reorienting themselves along a Sunni-Shia axis.

How will the Sunni governments respond to what they see as the renewal of historic "Persian imperialism" in the Middle East and especially in the Gulf? The evolution of the Syrian Civil War may lend an answer.

Iranian Arc of Influence across the Middle East

Jihadism and its use for political purposes is hardly new. It has been an integral aspect of Middle East history since the eighth century. Even in the 20th century, jihadism has been a recurring theme of Arab nationalism. Wahhabi inspired jihadism played a critical role in the formation of Saudi Arabia. Jihadism was also a prominent and recurring feature of the Muslim Brotherhood led nationalist movements in Egypt and Syria. Its prominence declined during the heyday of the "secular socialist," military led governments that dominated the region from the 1950s through the 1980s, only to reappear as those regimes turned increasingly to Islamic history and culture to establish their political legitimacy. In that sense, the rise of jihadism since the 1980s is simply the reemergence of a long-standing feature of Middle East politics.

Jihadism burst onto the international stage when the United States and its Gulf allies funded and organized the Afghan mujahideen prior to and during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. Called "Operation Cyclone" by the CIA, the campaign relied on militant Islamic groups organized by the Pakistani Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) to oppose the Moscow-backed government of Nur Muhammad Taraki, and later the Soviets. Between 1978 and 1992, the ISI armed and trained over 100,000 insurgents. They also recruited volunteers from Arab states to join the Afghan resistance fighting the Soviet invasion. Among the "Afghan Arabs" recruited was a young Saudi national named Osama Bin-Laden.

Leaders of the Afghan mujahideen resistance meeting with President Reagen in the Oval Office, February 1983. Picture courtesy Ronald Reagan Presidental Library

In total, the U.S. supplied some $20 billion to train and arm the Afghan resistance. It also supplied Pakistan with an additional $8.6 billion in economic and military assistance. Additional funds from the Afghan resistance came from Great Britain and China. The Arab governments in the Gulf also contributed heavily. Some of those funds were channeled through the CIA, and others went either to the Pakistani ISI or, on a few occasions, directly to the resistance groups. During this period the orientation of the jihadist groups organized by the ISI were anti-Soviet. While they were not necessarily pro-American, they were not overtly hostile to the United States.

The end of the Afghan war, and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union, made the anti-Soviet orientation of the jihadist groups irrelevant. In the meantime, the expansion of the American military presence in Saudi Arabia and the Gulf during and after the First Gulf War, and the increased prominence given to the Palestinian cause by jihadist groups, gradually shifted the focus of those militant organizations to opposing the U.S. role in the Middle East.

This reorientation gave rise to al-Qaeda and a range of other jihadist groups. This transformation was further reinforced by the subsequent U.S. led invasion of Afghanistan and then Iraq, and the emergence of a deep seated insurgency against the U.S. led military coalition there. Between the early 1990s and today, a little less than a quarter century, Islamic jihadism reoriented itself into a virulent anti-American and anti-Western ideology; one that has sparked numerous terrorist attacks throughout the world.

Al-Qaeda affiliated, al Nusra Front jihadists in Syria.

Middle East politics are increasingly moving toward a de facto proxy war between the Saudi led Sunni governments in the region and Iran and its Shiite allies. The fact that Tehran will eventually develop a nuclear capability as well, threatens to make the Middle East a larger version of the Indo-Pakistani proxy war in Kashmir. It's possible that, like Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and its Gulf allies will increasingly look to third party jihadist organizations, as they have in Syria, to counter Iranian influence in the region. If that happens, then it may well set the stage for a third reorientation of Sunni jihadism to focus on opposing Iran and its Shiite allies, and possibly move it away from its current focus of opposing U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East and Western culture in general.

The Islamic State (IS) has been both anti-Western and anti-Shiite. Indeed, one of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi's singular "contributions" to international jihadism was the demonization and targeting of Shiites. As a result, IS has, to varying degrees, radicalized other jihadist groups, including al-Qaeda, to also target Shiites. A post-Islamic State Middle East, however, could be a very different place.

Islamic State is unique in that it has become largely self-financing, even if that funding has been steadily declining. Stripped of its territorial domain, however, it would be, like other jihadist groups, dependent on outside aid and financing to be effective. It is unlikely that IS, as a militant insurgency rather than a would-be nation state, would prove to be any less anti-American or anti-Western. But a weakened IS could well be supplanted by a better-financed jihadist organization that would focus more on an anti-Iranian/anti-Shiite theme than an anti-American/anti-Western theme.

Former General and CIA Director David Petraeus at 2007 press conference.

It's also possible, although probably unlikely, that in a post-Islamic State Middle East, al-Qaeda might seek to fill this role. If that happens then Islamic State will have inadvertently accomplished something that would have been inconceivable a decade ago, the rehabilitation, or at least partial rehabilitation, of Al-Qaeda in Washington's eyes. Interestingly enough, retired Army general and former CIA director, David Petraeus, has already suggested that the U.S. should use "moderate" members of the al-Qaeda backed al-Nusra Front in its fight against the Islamic State.

To date, al-Qaeda has not given any indication that it is prepared to abandon its anti-American/anti-Western orientation. In fact, on July 24, al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, in an audio interview posted to al-Qaeda's website, urged militants to kidnap Westerners and hold them hostage to exchange for jailed jihadists. He noted that, "kidnapping was a powerful weapon in the fight against the enemy." The interview followed an attempt by two men, believed by police to be Middle Eastern, who tried to kidnap a British serviceman while he was jogging near the RAF Marham base, near Norfolk, East Anglia.

On the other hand, on Thursday July 28, Abu Mohammed al-Golani, the recently disclosed head of the al-Nussra Front, announced that it was "disassociating" itelf from al-Qaeda and that it would change its name to the Levant Conquest Front (LCF). He added that the decision had the support of al-Qaeda's leadership and that it was designed to allow al-Nusra Front to expand its cooperation with other Syrian rebel groups. It is also a not so subtle signal to Washington that it need not consider the LCF an enemy.

Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri

Al-Qaeda's anti-Americanism, while historic, is also, in part, shaped by its competition with Islamic State for the leadership of the jihadist movement. While the U.S. has decimated al-Qaeda's senior leadership and severely constrained its ability to operate and to launch attacks against Western targets, the U.S. does not ultimately pose an existential threat to al-Qaeda. The Islamic State, on the other hand, does pose such a threat.

Post-Islamic State, it's possible that al-Qaeda might moderate its anti-Western rhetoric. It's also possible that after 15 years of continuous warfare with the US, those views are so deeply engrained that they will never be abandoned. In which case, some other jihadist groups, more focused on countering Iran's power and less overtly focused on attacking the West, may, with generous funding from the Gulf States, emerge in the Middle East. Such a development, although unlikely to be publically acknowledged by Washington, would probably not be opposed either. This is after all the cauldron of Middle East politics. Stranger things have happened and, if history is a guide, will continue to happen.