The Panthers shut out the pack of zealous reporters and kept the door locked all day, but now the hallway was empty. Huey Newton and two comrades casually walked from the luxury suite down to the lobby and slipped out of the Hong Kong Hilton. Their official escort took them straight across the border, and after a short flight, they exited the plane in Beijing, where they were greeted by cheering throngs.

It was late September 1971, and U.S. national security adviser Henry Kissinger had just visited China a couple months earlier. The United States was proposing a visit to China by President Nixon himself and looking toward normalization of diplomatic relations. The Chinese leaders held varied views of these prospects and had not yet revealed whether they would accept a visit from Nixon.

But the Chinese government had been in frequent communication with the Black Panther Party, had hosted a Panther delegation a year earlier, and had personally invited Huey Newton, the Party's leader, to visit. With Nixon attempting to arrange a visit, Newton decided to accept the invitation and beat Nixon to China.

When Zhou Enlai, the Chinese premier, greeted Newton in Beijing, Newton took Zhou's right hand between both his own hands. Zhou clasped Newton's wrist with his left hand, and the two men looked deeply into each other's eyes. Newton presented a formal petition requesting that China "negotiate with... Nixon for the freedom of the oppressed peoples of the world." Then the two sat down for a private meeting. On National Day, the October 1 anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China, Premier Zhou honored the Panthers as national guests. Tens of thousands of Chinese gathered in Tiananmen Square, waving red flags and applauding the Panthers. Revolutionary theater groups, folk dancers, acrobats, and the revolutionary ballet performed. Huge red banners declared, "Peoples of the World, Unite to destroy the American aggressors and their lackeys." At the official state dinner, first lady Jiang Qing sat with the Panthers. A New York Times editorial encouraged Nixon "to think positively about Communist China and to ignore such potential sources of friction as the honors shown to Black Panther leader Huey Newton."

***

In Oakland, California, in late 1966, community college students Bobby Seale and Huey Newton took up arms and declared themselves part of a global revolution against American imperialism. Unlike civil rights activists who advocated for full citizenship rights within the United States, their Black Panther Party rejected the legitimacy of the U.S. government. The Panthers saw black communities in the United States as a colony and the police as an occupying army. In a foundational 1967 essay, Newton wrote, "Because black people desire to determine their own destiny, they are constantly inflicted with brutality from the occupying army, embodied in the police department. There is a great similarity between the occupying army in Southeast Asia and the occupation of our communities by the racist police."

As late as February 1968, the Black Panther Party was still a small local organization. But that year, everything changed. By December, the Party had opened offices in twenty cities, from Los Angeles to New York. In the face of numerous armed conflicts with police and virulent direct repression by the state, young black people embraced the revolutionary vision of the Party, and by 1970, the Party had opened offices in sixty-eight cities from Winston-Salem to Omaha and Seattle. The Black Panther Party had become the center of a revolutionary movement in the United States.

Readers today may have difficulty imagining a revolution in the United States. But in the late 1960s, many thousands of young black people, despite the potentially fatal outcome of their actions, joined the Black Panther Party and dedicated their lives to revolutionary struggle. Many more approved of their efforts. A joint report by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Central Intelligence Agency, Defense Intelligence Committee, and National Security Agency expressed grave concern about wide support for the Party among young blacks, noting that "43 percent of blacks under 21 years of age [have] ... a great respect for the [Black Panther Party]." Students for a Democratic Society, the leading antiwar and draft resistance organization declared the Black Panther Party the "vanguard in our common struggles against capitalism and imperialism." FBI director J. Edgar Hoover famously declared, "The Black Panther Party, without question, represents the greatest threat to the internal security of the country."

As the Black Panthers drew young blacks to their revolutionary program, the Party became the strongest link between the domestic Black Liberation Struggle and global opponents of American imperialism. The North Vietnamese -- at war with the United States -- sent letters home to the families of American prisoners of war (POWs) through the Black Panther Party and discussed releasing POWs in exchange for the release of Panthers from U.S. jails. Cuba offered political asylum to Black Panthers and began developing a military training ground for them. Algeria -- then the center of Pan-Africanism and a world hub of anti-imperialism that hosted embassies for most postcolonial governments and independence movements -- granted the Panthers national diplomatic status and an embassy building of their own, where the Panthers headquartered their International Section under the leadership of Eldridge and Kathleen Cleaver.

But by the time of Newton's trip to China, the Black Panther Party had begun to unravel. In the early 1970s, the Party rapidly declined. By mid-1972, it was basically a local Oakland community organization once again. An award-winning elementary school and a brief local renaissance in the mid-1970s notwithstanding, the Party suffered a long and painful demise, formally closing its last office in 1982.

Not since the Civil War almost a hundred and fifty years ago have so many people taken up arms in revolutionary struggle in the United States. Of course, the number of people who took up arms for the Union and Confederate causes and the number of people killed in the Civil War are orders of magnitude larger than the numbers who have engaged in any armed political struggle in the United States since. Some political organizations that embraced revolutionary ideologies yet eschewed armed confrontation with the state may have garnered larger followings than the Black Panther Party did. But in the general absence of armed revolution in the United States since 1865, the thousands of Black Panthers -- who dedicated their lives to a political program involving armed resistance to state authority -- stand alone.

Why in the late 1960s -- in contrast to the Civil Rights Movement's nonviolent action and demands for African Americans' full participation in U.S. society and despite severe personal risks -- did so many young people dedicate their lives to the Black Panther Party and embrace armed revolution? Why, after a few years of explosive growth, did the Party so quickly unravel? And why has no similar movement developed since?

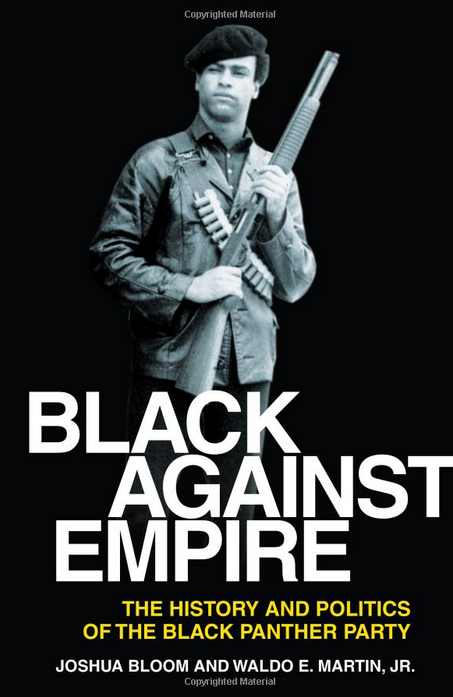

Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (George Gund Foundation Imprint in African American Studies). University of California Press.

Joshua Bloom is a Fellow at the Ralph J. Bunche Center at UCLA. He is the co-editor of Working for Justice: The L.A. Model of Organizing and Advocacy and the collection editor of the Black Panther Newspaper Collection.

Waldo E. Martin, Jr. is Professor of History at UC Berkeley. He is the author of No Coward Soldiers: Black Cultural Politics in Postwar American, Brown Vs. Board of Education: A Brief History with Documents, and The Mind of Frederick Douglass.