When the Baltimore Orioles begin playing for the American League Championship series tonight, on the line will be not only their reputation but that of one of the most colorful franchises in baseball history: the St. Louis Browns, from whose ashes the Orioles rose like a phoenix exactly 60 years ago this year.

The transition of the forgotten St. Louis Browns to the triumphant Orioles is a study in redemption. Today it is difficult to identify any other team in the history of professional sports that has been so celebrated for its own ineptitude as the Browns. A case can be made for other worst-evers --the "Amazing" New York Mets of 1962 or the 1959 Philadelphia Phillies. Then there were the long-forgotten Cleveland Spiders of the old twelve-team National League. In 1899, the Spiders finished last with a record of 20 wins and 134 losses.

But while each of those teams enjoyed some flashes of success during their long travails over the years, the Browns maintained a level of failure that remains almost unequalled in its consistency. From their beginning in 1902 until their end a half-century later, the Browns compiled a won-loss record of .433, the lowest of any major-league team ever. They led the league in errors 14 times, six of them in a row. In 1939 they lost 111 games and gave up 1,035 runs, or about seven a game. They made 199 errors and finished 64 and one-half games out of first place.

"This was not a team, it was a disaster," wrote the sportswriter Jim Murray. "It didn't need owners, it needed the Red Cross." The Browns' closest brush with success came in the talent-depleted wartime season of 1944, when they made it to the World Series -- despite fielding 18 players classified as 4-F - but were quickly dispatched by their hometown rivals, the Cardinals.

The following season the Browns played a sullen and moody outfielder named Pete Gray, who had the singular handicap of having only one arm, his left. He had lost his right arm in a childhood wagon-wheel accident. (Gray was not the first handicapped Brownie: in the previous century, the Browns played a deaf player with the evocative name of Dummy Hoy.) Gray batted .218 in 61 games, good enough to attract plenty of publicity, but some of his teammates believed his unorthodox if dexterous fielding -- he both caught and threw the ball with his left hand -- cost them a half-dozen games. By the time 1950 arrived, the owners had resorted to hiring a hypnotist, David Tracy, in a failed attempt to mesmerize the team out of its misery.

In the spring of 1953, however, the Brownies had unaccustomed new hope in the person of one of the most arresting personalities in the history of American sports. Bill Veeck was an American original, a disruptive figure long before that concept existed. An ebullient redhead who had grown up in baseball, Veeck had bought the Browns in 1951 at the age of 37. His father was a Chicago sportswriter who had become president of the Chicago Cubs when Bill was four years old. As a boy, Bill had literally helped plant the distinctive ivy on the outfield wall that is the trademark of Wrigley Field. He had attended the patrician Ranch School in Los Alamos, but had dropped out of it and later Kenyon College to pursue his own eccentric if often successful path.

In December 1943, as a 29-year-old father of three, Bill enlisted with the Marines and volunteered for combat duty. He saw wartime duty in the Pacific, but an artillery-shell accident sent him home and its complications eventually cost him most of his left leg below the knee. H returned to baseball and, after reviving the Milwaukee's minor league franchise, in 1946 Veeck put together a syndicate to buy the Cleveland Indians. Suddenly on a major-league stage, he set about to remake the franchise. "When [Veeck] took over," wrote his biographer Paul Dickson, "the team had no radio broadcasts, no Ladies' Day, no posting of National League scores, and no telephone service for fans wishing to reserve tickets. All these things were changed in a matter of weeks."

Most dramatically, Veeck set about to integrate the rigidly traditional American League. The New York Yankees (among others) had dug in against integration, but Veeck signed Larry Doby just eleven weeks after Jackie Robinson integrated the National League. In the face of widespread skepticism, he then signed the legendary Satchel Paige, then 42, but arguably the best pitcher in baseball history. In his first three starts with Cleveland, Paige drew more than 200,000 fans, including pitching successive shutouts against the White Sox. (An astonishing 78,382 fans turned out one night to see Paige win a three-hit shutout. It was then the largest night-game crowd in baseball history.) Behind the pitching of Paige and Bob Feller, the Indians surprised everyone by winning the 1948 World Series.

Veeck's commitment to racial integration did not stop with his marquee players. He hired African-Americans throughout the entire organization, from ticket takers to security guards to the public relations office. Elsewhere, he had 14 black players under contract throughout the organization.

After the games, Veeck plunged on into the night -- roistering and nightclubbing at favorite nightspots in New York such as Toots Shor's and the Copacabana. Veeck's reputation was not diminished by his flamboyant personal style -- the papers called him "The Sportshirt" for his ever-present flaring, unbuttoned collars -- and he conducted press interviews in his office while soaking his wooden leg in a bucket of water. A four-packs-a-day smoker, Veeck would startle visitors by flipping his cigarette ashes into a receptacle carved into his prosthesis.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Veeck's wife Eleanor, far more reclusive than the flamboyant Bill, filed for divorce early in 1949 season on the grounds of desertion. To pay for the settlement Veeck put the Indians up for sale. Before the end of the year, he had sold the team for $2.2 million to a group of Cleveland businessmen. But as Time reported, Veeck "had turned the crank that gave [Cleveland] its dizziest merry-go-round in years ...."

Bill could not stay out of baseball or -- marriage -- long. In 1950 he had remarried - to Mary Frances Ackerman, a press agent who worked with the Ice Capades. Then in the spring of 1951 he learned that the St. Louis Browns were in financial trouble and that the DeWitt brothers were looking to sell the franchise. Veeck scrambled to put together an investment syndicate and, on July 5, 1951, he became the principal owner of the Browns.

It was a dubious distinction. When Veeck bought the Browns they were 23 and 1/2 games out of first place and embodied St. Louis's self-mocking slogan: "First in shoes, first in booze, and last in the American League." Veeck took on the Sisyphean task of rebuilding the Browns' attendance with a series of stunts. How to get press? Veeck put in the 3'8" Eddie Gaedel to bat as a pinch-hitter. (He walked.) How to get the fans more involved? Veeck mailed out placards to a designated section of fans, who could then weigh in on managerial decisions without leaving their seats. Should the Browns bring in a pinch-hitter? The fans voted by holding up signs reading, "YES" or "NO". The Browns won that game, but by the time that the 1951 season ended, the Sisyphean boulder had rolled back: they finished 46 games out of first place and, over the course of the year, had drawn a full-year home attendance of under 300,000, barely more than the Indians might bring into their stadium over a holiday weekend.

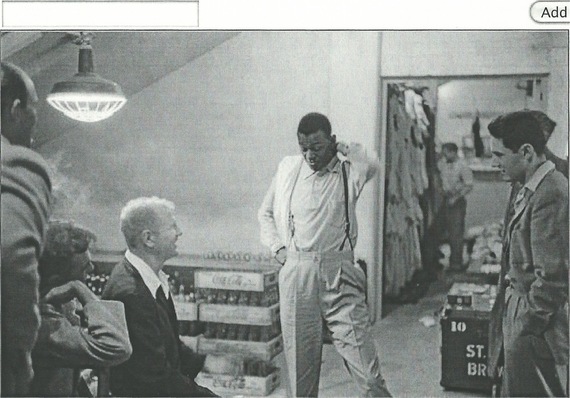

Veeck also turned once again to Satchel Paige. Though pitching mostly in relief, Paige had won ten games for the Indians in 1948 and 1949. He spent the 1950 season pitching for whoever would pay him -- the Minot (N.D.) Mallards and the all-black Philadelphia Stars and a black all-star team, the Kansas City Royals. But in 1951 Veeck brought Satchel back to the big leagues in St. Louis and, in yet another publicity gesture, outfitted the bullpen with a rocking chair for the 45-year-old pitcher to use during home games. In the 1952 season, Paige pitched creditably for the seventh-place Browns, winning 12 and losing 10, with a 3.07 ERA, good enough to be named to the American League's All-Star Team.

Veeck decided to raise the stakes in his battle for market dominance against the Cardinals by raiding the National League team's trophy case. First was Rogers Hornsby, one of the greatest hitters in the history of the game, whose batting average of .424 in the Cardinals' 1924 season remains the highest in modern baseball. The cantankerous Hornsby would become the Brownies' new manager. At shortstop Veeck hired the smooth-fielding Marty Marion, who had played for the Cardinals from 1940 to 1950. In 1944 -- the year the Cardinals beat the Browns in the World Series -- Marion was the National League's Most Valuable Player. Veeck also picked up Harry (The Hat) Brecheen), a left-hander who had won three games for the Cardinals in the 1946 World Series against the Red Sox. In the radio booth he deposited another Cardinal icon, the folksy Dizzy ("He slud into third") Dean, who had won 30 games in 1934 for the Gashouse Gang.

By the end of the 1952 season, the Browns' home attendance had nearly doubled to 518,796, their second-highest draw in 25 years, but still far below the Cardinals' total of 913,222.Veeck promptly plunged $150,000 of the receipts into buying the contract of Billy Hunter, a promising 24-year-old shortstop in the Brooklyn Dodgers farm system, and trading with the Detroit Tigers for Virgil Trucks.

Trucks was one of many players on the 1953 Browns who would eventually find distinction after leaving the team. At first base was the hard-hitting Roy Sievers, a high-school star from St. Louis who had been American League Rookie of the Year for the Browns in 1949; he would go on to hit 42 homers for the Senators in 1957. Statistics buffs still argue over whether Sievers is the best play in baseball history never to make the Hall of Fame. In the outfield was Vic Wertz, who would bat .277 over his 17-year career but is best remembered today for a single out -- his long drive to centerfield in Game 1 of the 1954 World Series that Willie Mays caught over his shoulder. In addition to Brecheen and Trucks, the pitching staff included a powerfully built rookie fresh out of Korean War service, Don Larsen. A few years later, given redemption as a New York Yankee, Larsen pitched the only perfect game in World Series history. But now he was another rookies trying to make the Browns.

And then there was Satch. The greatest pitcher in the history of the Negro Leagues, Satchel Paige had illustrious careers both behind him and in front of him when Veeck first signed him for the Indians in 1948.

At spring training, sportswriters observed that, along with Paige and non-roster pitcher Harry Wilson, another black outfielder named Phelps was getting a walk-in tryout, thus making "three Negroes in camp." Although Jackie Robinson had integrated the major leagues six years earlier, the writers marveled with astonishment that, when Wilson pitched in one spring game to catcher Charlie White, the Browns had played behind "a Negro battery" for an entire inning.

Away from the bright California sunshine, however, another baseball narrative was unfolding in St. Louis. Although the city's population was near its historical high of 857,000 residents -- eighth largest in the country -- it was an uncomfortably small market for two big-league baseball teams. Bill Veeck estimated he needed to sell 850,000 tickets a year to break even, but even the Browns' improved gate of 518,796 in 1952 was well short of that. His share of revenues flowing from the new medium of television was uncertain. The major league ball clubs would be regularly televising their road games for the first time in the 1953 season. The hapless Browns had no chance to land a deal to have their road games televised.

The one hope Veeck had was to outflank the Cardinals' owner, Fred Saigh, a local real-estate developer. While both teams shared the ancient Sportsman's Park, the Browns owned the stadium itself. The Cardinals were tenants. Veeck moved his family into the ballpark, converting some dusty offices into a ten-room apartment. When it came time to paint the stadium, Veeck of course painted it brown to annoy the Cardinals. And for good measure, he installed large photos of oldtime Brownies in the passageways beneath the stands for the Cardinals' fans to admire.

As the owner of the stadium, Veeck might have been able to outlast Fred Saigh in a long war of attrition in St. Louis. But then, as always, human frailty produced unforeseen consequences -- Saigh was indicted and eventually convicted of income-tax evasion. For an owner of a major-league franchise to play fast and loose with other people's money was business as usual in baseball; to serve hard time in prison was not. After shopping the team to prospective buyers in both Milwaukee and Houston, Saigh found a buyer at home: Anheuser-Busch, the nation's biggest brewery, run by the flamboyant August A. ("Gussie") Busch Jr.

Now, instead of competing with a single, idiosyncratic proprietor, Fred Saigh, Veeck found himself facing one of the nation's best-known brands, Budweiser, armed with an immense marketing budget and led by a CEO with an ego as large as Bavaria. Gussie Bush was already talking about televising some of the Cardinals' road games, a potentially fatal blow to the Browns' attendance at home those same nights.

Veeck spent most of the spring of 1953 quietly investigating moving the Browns' franchise to another city. That idea alone was enough to make the spheres wobble. The Browns had played in St. Louis since 1876. The nation's sixteen major league teams had been playing one another, unchanged, for a half-century. In a single summer's night, Americans could watch every one of their big-league teams in just eight ball parks.

Veeck first thought of moving to Milwaukee, where he had successfully revived the minor-league Brewers. The city had built a new $5 million stadium to allure a big-league tenant. But another struggling franchise, the Boston Braves, had veto rights through its ownership of the Brewers - and their owner, Lou Parini, was thinking of moving the Braves to Milwaukee. For Veeck, the Milwaukee deal was dead on arrival.

But what about Baltimore? It's Babe Ruth Memorial Stadium could seat 40,000, a hefty increase over the 33,000 rickety seats in Sportsman's Park. The Baltimore mayor was willing to talk. Not only that, he would help Veeck clear the way by purchasing the resident International League team, the Baltimore Orioles, who would be removed to Toledo under a new name. On Friday, March 13 - "BLACK FRIDAY FOR ST.LOUIS FANS" headlined the Post-Dispatch - the news broke that Veeck had reached a deal not only to move his franchise to Baltimore but would in fact open the season there on April 14.

To raise cash for the deal, Veeck would sell the venerable Sportsman's Park to the Cardinals. The first major-league franchise move in 50 years seemed imminent. All Bill Veeck needed was the pro forma approval of the five of the American League's other seven owners. The American League's president, Will Harridge, told the Washington Post that the owners would approve it unanimously. It would be as easy as turning a routine double play.

Or would it? Most of the American League's owners detested Veeck and were still smarting from his promotional shenanigans. When Veeck proposed that television revenues from road games be shared, the Yankees refused to schedule a single night game at home with the Browns. The other owners deeply resented him for going around them to approach Baltimore's city officials and arguing his case in the press. It was no secret that most of them would be delighted if this unorthodox outsider either lost his shirt or was forced out of baseball.

Meeting in Florida, the American League owners voted, 5-2, to block the transfer of the Browns franchise. "It would have been nonsensical to make the move so close to the start of the season," commissioner Ford Frick explained to the reporters gathered at the Tampa Terrace Hotel. "We would have been up to our necks in lawsuits." Closer to the truth was the fact that the Washington Senators, their attention focused wonderfully by the prospect of competition in nearby Baltimore, had dug in and organized the opposition.

The citizens of Baltimore erupted that they had been "double-crossed." Veeck was even more vehement. Stating that he had lost $400,000 on Browns in 1952, he now insisted that St. Louis could not support two teams and admitted that he had been trying to move to a new city since the previous summer, but "I was afraid I would go broke in the process." Two days later, the National League's owners put another finger into Veeck's eye by approving the move of the Boston Braves to Milwaukee.

Baltimore mayor Thomas D'Alessandro was threatening to sue the American League to force the team's move to Baltimore. As D'Alessandro told reporters, "I have plenty of friends in Congress" -- which he indeed did later when his daughter Nancy Pelosi later became Speaker of the House. Evidently he did then, too. The Justice Department promptly announced that it was opening an antitrust investigation of professional baseball, a prospect that disconcerted more than a few owners.

The Browns played through a dispiriting 1953 season, losing 100 games, including 20 straight games at home in one dismal stretch. On Sept. 29, 1953, the American League owners met and approved the sale of the team to a Baltimore consortium -- but only with the guarantee that Veeck would leave the team and be out of baseball. "I hadn't thought they hated me that much," Veeck said. Not everyone did. Paul Dickson cites the Detroit owner Spike Biggs saying at the time, "Veeck's good for baseball. The people who were trying to keep Baltimore out of the American League are not."