I am not cruel, only truthful---

The eye of a little god, four-cornered.

Mirror, Sylvia Plath

Diane Arbus famously brought a dispassionate but probing voyeurism to the marginalized and pariah of our society. Her treatments of the denizens of the mainstream are no less discomfiting. In "Diane Arbus 1971-1956," Fraenkel Gallery has assembled 60 photographs of the late artist and grouped them according to themes strained from Arbus's notebooks and letters. Images appear in reverse chronological order in groups under "The Mysteries that Bring People Together," "Interiors: The Meanings of Rooms," "People Being Somebody," "Recognition," and "Winners and Losers," headings chosen and curated by Jeffrey Fraenkel.

The categories are hardly beyond questioning. In the coyly-titled Two friends at home, N.Y.C. 1965, what is apparently a lesbian couple stand in their bedroom. One, in a skirt, pointy glasses, and a feminine updo, rests her arm around her lover's shoulders. The other, in pants and a man's shirt and slicked-back, cropped hair, looks at the camera, with her hands in her pockets. The image would make sense under "The Mysteries that bring people together." It could reasonably fall under "People Being Somebody" -- after all, one could deduce from the women's costume and toilette that they self-identify as "femme" and "butch." Depending on one's views on love and its pitfalls, and the fact that one woman looks hard into her lover's face, while her lover in turn looks away -- it could even reasonably be included as a witty addition to "Winners and Losers." But Fraenkel has placed the image with "Interiors: the meanings of rooms." This compels one to examine the room the lovers are placed in with a mind to divining its significance, and possibly to give it more interpretive weight than if one were simply considering all elements of the picture equally. And so the eye falls on the crumpled bed, admittedly bestowed importance if not primacy by the photographer by its large and central place in the composition, and the fact that aside from the windows, it is the brightest thing in the frame. It is also the scene of their perceived crime, for even in a progressive city like New York, in the years preceding Stonewall there were still laws limiting the rights of LGBT people, as well as widespread casual harassment and prejudice. The "meaning" of their room is different from that of other couples' rooms: it is not only the seat of intimacy but a hideout from the nosy hostility of a benighted era. Thus Fraenkel's categorization draws historical and social context into the picture, steering us to consider it through an interpretive lens determined not by Arbus or by our own proclivities, but by Fraenkel himself. One can resent the imposition or be grateful for it -- indeed, there are worse people than Jeffrey Fraenkel to be guiding one's examination of photographs. His exhibit from earlier this year, "The Unphotographable," demanded (and rewarded) a rigorous intellectual engagement with the pieces, the unphotographability of which was in many cases due to the fact that the subject was an idea rather than a visible object -- the moment of death, a dream, the passage of time, the enormity of an event like 9/11. But while in that show, it was understood that many of the artists had been grappling with that subject -- how to photograph something that isn't "so readily seen" -- the themes of this show were not chosen by the artist but by the gallerist showing her work, themes that he gleaned from her notebooks and correspondence and that he determined to have special importance, and then grouped the images according to his own interpretations of them. It is a muscular, even manipulative, curatorial conceit, and one that invites skepticism. However persuasive are Fraenkel's extrapolations, they necessarily say more about Fraenkel himself than they do about Diane Arbus. However one might wish to achieve some hermetic communion with her work, one ends up examining it under the considerable influence of his subjective take on it.

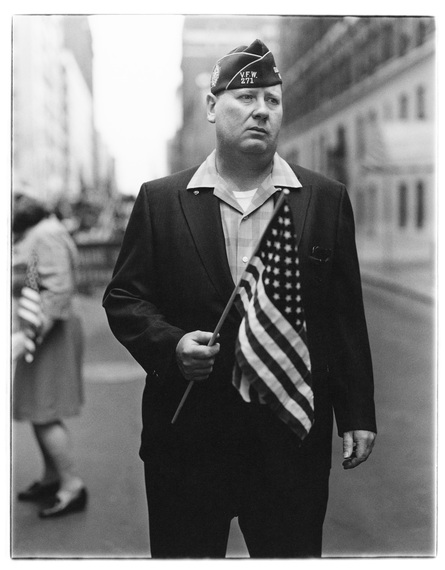

Of course that hermetic communion is impossible anyway; Arbus's fame is too great and many of the images in the current exhibit are renowned in the canon. Even the less well-known ones lend themselves to being viewed as examples of the scholarly sang froid that won Arbus her place in the pantheon. Such photographs as A blind couple in their bedroom, Queens, N.Y. 1971, which depicts a couple relaxing in each other's arms on their bed, a representation of tenderness so much like any other except for that thing that is not quite right about their eyes, or Santas at the Santa Claus School, Albion, N.Y. 1964, men of mid- to late-middle age who in their youth one might assume had different career goals from this -- "Diane Arbus: 1971-1956" is full of depictions of both marginalized people and the marginalia of the quotidian, depictions that are neither judgmental nor particularly compassionate, revelations of the kind of lives we might dread to lead, without the assuasive evidence of redemption. The people she referred to in her letters as "retarded," "freaks," "morons," "mongoloids," "idiots," and "imbeciles" (which, even in that era of unreconstructed attitudes and language, one suspects were not the kindest words to use about her varied subjects) appear without sentimentality, without the sort of visual euphemisms an artist might use to soften a difficult and fearsome subject. Take Five Children in a common room, N.J. 1969: mentally and/or physically impaired kids play or just sit in probably the world's grimmest common room (bare walls and a toddler's tricycle, it seems, were deemed enough to create a jolly atmosphere for these children, one of whom appears to be a teenager). They live with conditions each of us counts ourselves lucky not to be burdened with, and fear to pass on in our own progeny; they scare and shame us -- "What if that were me?" "Why is he smiling like that?" "Why do I complain about anything in my life, ever??" Yet Arbus doesn't labor to show their humanity, or offer any sort of palliative to our traumatized sensibilities. Even her photographs of people who aren't necessarily "freaks" showcase her unmerciful truthtelling. Veteran with a flag, N.Y.C. 1971 doesn't appear extraordinary at first. He wears a nice blazer, a clean shirt with a starched collar, and his Veterans of Foreign Wars hat, and he holds an American flag. He could be taking part in a Veteran's Day parade celebration. But he's relaxed his grip on his flag, which seems like it might slide through his fist at any moment. He is distracted -- by what? It could be something happening in the street, or it could be what he has seen, as a veteran of any of America's grisly 20th century wars. The look in his eyes doesn't exactly scream, "'Murricuh!". It just screams. Possibly something more like, Oh woe is me, to have seen what I have seen, see what I see. It is hard to resist making deductions from the pairing of that cheap, crumpled flag with the abject expression on the soldier's face, and that is also what makes the image hard to look at. Some of Arbus's subjects were marginalized by nature; others by their society or their place in history. She takes what we don't like to look at and shows it to us anyway, offering no cheap promises to reveal some hidden beauty in it. One gets the sense that Arbus expected her viewers to be made of sterner stuff than those who would require a side of uplift to make their hard truths more palatable.

DIANE ARBUS

Veteran with a flag, N.Y.C. 1971

© The Estate of Diane Arbus

All of this aligns with the received interpretations of her work, or at least doesn't deviate too dramatically from them. And so one could view the images in "Diane Arbus 1971-1956" as emblematic of her oeuvre and fame. But then there are those categories again, which at first seem so arbitrary, not least because many of the images could be made a case for as being equally suited to the categories that they don't appear in. But a strange thing happens when one does regard them with Fraenkel's delineations in mind. As in Two friends at home, the focus of the photographs is no longer the subjects themselves, or the "freakish" things about them that inspired Arbus to seek them out, but rather something more complicated, possibly unphotographable. Five children in a common room appears under "Interiors: the meanings of rooms." Well, obviously, you could say; the common room is where the children converge and play and fight and make noise. But is there a greater significance to this particular room that could justify Fraenkel choosing this apparently redundant heading? Think of the childrens' rooms you've seen and been in, whether they were in homes, classrooms, daycare or community centers. Now try to remember a single one that did not have some sort of decorations on the walls for the kids to look at, or age- and size-appropriate toys to play with. People who care for "normal" children make an effort to create a space for them that is both sensorially stimulating and joyful. For the children in Arbus's "common room," however, it was considered sufficient to herd them into a low-ceilinged cell with blank walls, dingy floor tiles, and a trike none of them can actually ride. The significance of this room is the revelation of our unconscionable negligence towards the people we've decided just aren't worth the bother. The most brutal Arbussian truth in this image isn't about the children; it's about us.

And the Veteran -- he appears under "People being somebody." Well, yes, he is a veteran. But "He is somebody" is different from "He is being somebody." "Being" somebody is assuming a role, like an actor; it connotes effort and deliberation, a distance between the private and presented selves. There is a chasm between the jaunty hat and flag and the thousand-yard stare, just as there is a chasm between wars and the parades that commemorate them. In his youth this man might have been sent to do the very worst things it is possible for one human being to do to another. The same country that asked, or ordered, him to do that, now gives this grown man some cheap felt and a toy flag to wave and expects him play this bloodless, PG version of the conquering hero, pretending that the one has anything to do with the other, even, astonishingly, that the latter is a sort of reward for the former. The image is especially damning now, considering that our present veterans are struggling to win the kinds of compensation previous generations were guaranteed, like healthcare and education. The veteran isn't unusual for trying to be the man his country expects of him. But what sort of country expects him to be this man?

It is hard to view Arbus's work uninfluenced by the pervasive mythology around it. Anyone who's never seen an Arbus photograph in person may nevertheless be familiar with her as the photographer of "freaks" (a designation she bristled at). What Fraenkel's thematic groupings have done is to shift the focus of each image to the unexpected, and so encourage the viewer to glean from it something different from what the mythology would indicate. Again and again, when traveling through the galleries and examining each photograph, the headings they are grouped under cause one to do a mental double-take. A dominatrix and her client are not just a sad, paunchy little man in socks and his hired fetish. They're two people, like any other two, in a heartbreakingly tender embrace that transcends commerce and conceals the 'mystery that brought them together.' A girl and boy in Washington Square Park stare out through very stoned eyes. Fraenkel asks us to do more than gawk at the hippies as another of Arbus's coldblooded anthropological studies, and invokes "Recognition." This brings our focus out of the image and into the space between it and us. What is it the kids are recognizing? What might we recognize in them? The headings redirect our focus to something left out of the visual plane, that the imagination must conjure and have a good wrastle with, something unphotographable. Whether Arbus herself had any such ideas about her work is immaterial; the risk one takes in making art is that someone else will re-envision it in a way that is as provocative as it is irrelevant, as enriching as it is dubious. Jeffrey Fraenkel's exercise is an example of how good curation can clear away the fumes of legend and present work we think we know, afresh.

Well-played, sir, well-played.

"Diane Arbus 1971-1956" is on display at Fraenkel Gallery through December 28.