Last week I posted about the time it took for me change my occupation on various official forms to "Stay-at-home dad."

My pro forma occupation was something I hadn't thought much about until an Airport Customs Officer commented I was the first stay-at-home dad he had processed, and I realized that it was probably the first time I'd listed it as my job. I'd been doing it for five years. Both facts got me thinking and eventually writing.

It turns out many of my stay-at-home mom friends also struggle with what to label themselves. Many condoled me, that if it was hard for them, it must be really hard for a man.

While that was gracious, there is a certain ill-defined novelty to being a stay-at-home dad that works in my favor. My female peers came of age in the 1990s when cultural perceptions of motherhood were sharply divided on whether you bought or baked cookies. Fortunately, I don't have all that attendant baggage.

But why do we stay-at-homers struggle to call ourselves parents? Is it because we devalue parenting?

Every year, in the week before Mother's Day various people try and put a value on mothers. See, I told you the stay-at-home dad is still a peripheral figure.

According to one site trying to sell life insurance a mom is worth $1,105,518 over 20 years. An annual salary of $55,276 or $16.27 hourly. This is based on the cost of replacing the labor of a parent in the open market.

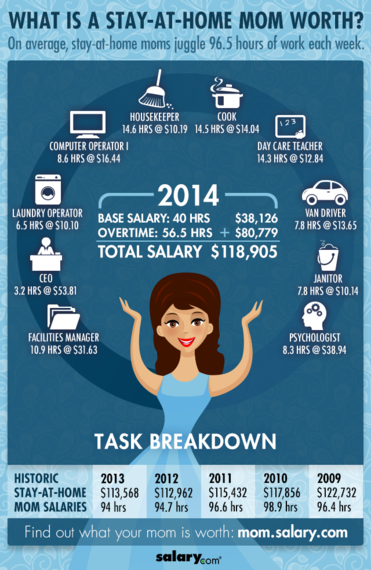

Salary.com is a little more generous in its methodology, crediting moms with professional wages for the portion of their time spend doing things like being a CEO or a psychologist. In 2014 they said a mom was worth $118,905 a year. Based on a 40-hour week that sounds like a good gig until you read the fine print; she works 56.5 hours of overtime! That is $23.70 an hour over 52 weeks, because we all know parents don't get paid holidays.

However you do the math, it makes an interesting contrast that with the result of a quick survey of five of my fellow stay-at-home parents. When we left the workforce our average salary was $75,000, and our average year of departure from paid employment was 2005. What would our collective income be today?

There are plenty of people who say parenting is the most important job in the world, but that is not reflected in cold, hard cash. Is our struggle to put our occupation as a parent a symptom of society's wider reluctance to put real value on child raising?

Is not just parenting. Look at teaching. As a profession it has been dropping in status, and I suspect, relative pay for a couple of generations.

You could argue that these figures reduce parenting to a series of low-paid largely menial jobs; cook, launderer and chauffeur, with a dash of tutor and accountant on top.

Parenting has its share of mundane moments, dead-end yes or no answers, and mind-bogglingly inane arguments about whom did what to whom. On balance there is probably more drudgery than a job with a $75,000 salary, but there is more to being a parent than that. None of my mother friends, who struggle with calling themselves parents on a form, are about to give it up in despair.

Well, I'm the man among them, so I'd probably be the last to know.

Now, I'm a cup half empty guy, so if anyone is going to dwell on negative side of life it is me. I remember calling my mother one particularly rough day with a baby and declaring that I could see why feminism held a certain appeal to many women of her generation. And it is telling that the movement has largely been one-way; away from being at home and towards the option to engage in the world.

But feminism was not a rejection of parenting. It was a reaction to being told what to do, to living a narrowly proscribed way of life. Unfortunately, that "life" was in the domestic sphere, which is why feminism so easily became an argument about cookies.

We stay-at-homers have made a choice to do this. The choice was obvious in our marriage. My wife is much more career orientated than I am. Her drive is greater, her earning potential is higher. Our contribution to the Gross Domestic Product of this country, and a few others, is exponentially greater with her in the workplace.

It's a tragic to think that had she been born two generations earlier her potential would have been arbitrarily limited. That said, she would have been a great stay-at-home mother.

It strikes me this could be a particularly upper middle-class problem. We come from the class that can afford to have one parent stay-at-home, but entry into that class in the first place implies a higher level of education and vocational achievement, and with that come increased expectations of life.

So perhaps it is our constant quest for growth and advancement, for a meaningful life, that has put us on this course. The suspicion that we are no more valuable than a collection of hands-on tasks irks us. We have become conditioned to want more.

That's quite a leap in two blog posts. Truth is, it's been more a fun musing than an existential reckoning, but it's not a conversation I could have had in the car driving my 8-year-old to piano.

Which I must now do.

Crap, I'm late!