PTSD, Depression, abuse of alcohol and drugs, and psychosis are pervasive, insidious forms of mental illnesses seen in Vets who commit crimes. Are they mad or bad?

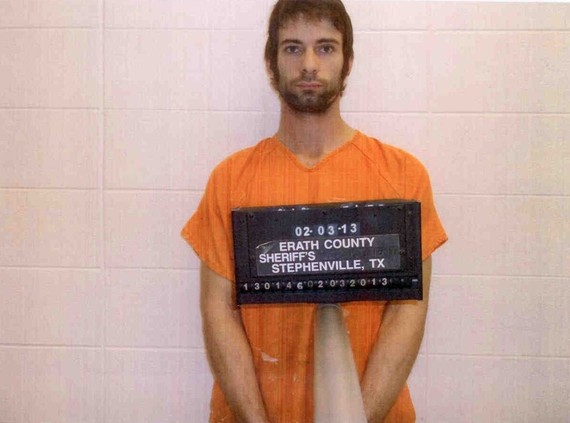

The capital murder trial of Eddie Routh, the Marine veteran accused of killing sniper Chris Kyle, portrayed by Bradley Cooper in American Sniper, and Kyle's friend, Chad Littlefield, has begun in Erath County, Texas.

After the slayings, which Routh has admitted to, he told his sister and her husband that while at a target practice range "...he couldn't trust them so he killed them before they could kill him." Kyle had taken Routh to the range to help him in his recovery from the "invisible wounds of war," namely mental illness. Chris Kyle had found helping Vets recover from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan his calling and his means of rebuilding a life personally scarred by four tours of duty and more "kills" than any other sniper in history. He paid the ultimate sacrifice for his remarkable mission.

Routh's defense attorney is pursuing the "insanity defense." He will not only have to prove that Routh was mentally ill but also that he could not tell right from wrong, the standard in this country for court determinations of "Not Guilty by Reason of Insanity" (NGRI).

Routh is reminiscent of the 20-year-old Army private, David Lawrence, deployed to Afghanistan, who on October 17, 2010, shot and killed a captured Taliban soldier he had arranged to guard. Controversy ensued: was he a criminal or mentally ill? Was he feigning madness to elude punishment?

A military court at Fort Carson, Colorado, in May of 2011, accepted a guilty plea to premeditated murder. The media reported this as a deal to a reduced prison term of 12.5 years, instead of possible life imprisonment, with a dishonorable discharge. He continued to carry the diagnoses of schizophrenia and PTSD.

Both these chilling stories, and the others we have seen reported, reminded me of an experience I had over 40 years ago as a first-year resident in psychiatry on rotation at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Syracuse, NY.

Syracuse Veterans Hospital, psychiatric unit, circa 1971

I looked like any young resident, wearing my white waist-length coat with stethoscope hanging out from a side pocket and showing signs of exhaustion from too much on-call duty, bad food, coffee, and apprehension about what I was trying to do. I had begun my rotation on a VA psychiatric unit for Vets, all men, with serious mental illness.

Veterans with disabling mental problems usually remained on this unit for many months for extensive evaluation and, when diagnosed as mentally ill, for treatment. I had 7 men under my care. On the first day, I introduced myself to my patients and tried to instill in each of them some confidence in their new doctor. I knew their stories, at least as they were portrayed in the medical record. The psychiatric illnesses of all these patients -- except for one -- were familiar to me.

He looked like any gangly, ill-at-ease 19-year-old. Only he was missing a finger on his left hand. Billy seemed passively resigned to being on the psychiatric ward, along with about 50 other men. He had appeared before a military court for theft, but because there was considerable suspicion that he was mentally ill an evaluation was ordered to determine whether he was mentally ill and should receive treatment, not a prison sentence. My job was to evaluate and treat him, and then make recommendations to my supervisors who, in turn, would report our findings to military officials.

The first thing Billy said to me was that he had trouble sleeping. Even a young doctor knows that is usually a plea for sedatives that can be used to get high; he wanted a good-night intoxicant. Combining a sleep medication, a pain killer, and a tranquilizer will give almost anyone a "buzz." I decided to meet him halfway. We agreed on an evening medication cocktail that would help him sleep but would have little likelihood of delivering a high (or producing abuse and dependence). We also agreed to meet daily to talk about his life and the trouble he was in.

Billy was 18 when he was drafted. The war was raging in Vietnam. Deferments went to the educated and those who had connections -- not to poor kids from upstate New York with high school educations. After basic training, he was deployed to Vietnam, where he signed up for the "graves detail." He told me,

Every day at dawn a small patrol of GIs was sent out to recover American bodies. It was awful but not so dangerous because the fields had been heavily patrolled and there weren't many snipers, ambushes, or landmines. There were also dead enemy combatants lying around, and the "graves detail" could put them in body bags, if we wanted. We would get high on dope before we went out on detail. I got really out of it. I took a lot of drugs, like the others, and everything was a haze.

Pretty soon we started robbing the bodies. We took things from American troops and sometimes there even was something worth taking from the enemy. We looted watches, rings, money . . . some GIs carried all kinds of weird things too. But we got caught. I knew I would be court martialed. That was when I shot my finger off with my service revolver.

Billy intrigued me. He was aloof, preoccupied, highly anxious, and often paranoid; sometimes, he heard voices. Was what he did to himself a sane response to insane circumstances? Was he someone feigning madness after having been caught for criminal activity as might a psychopath (a person with an antisocial personality disorder, which is not a mental illness)? Or had he become psychotic and could not distinguish reality from fantasy? How did his abuse of drugs influence his judgment and behavior? Was there something in Billy's life and history that would explain his strange behavior, short of the Vietnam hell where he met danger, drugs, and death at every turn?

A good psychiatric evaluation generally can make the distinction between criminal behavior and mental illness. If the antisocial personality disorder, a character disorder not amenable to psychiatric treatment, drove the illegal act it is criminal behavior; if the crime was a consequence of a mental illness, including not being able to tell right from wrong at the time the crime was committed, a person is admitted to a psychiatric hospital for treatment. Such a hospitalization lasts until physicians and the court decide the person is no longer a threat to the community, which is an indeterminate time that could last longer than time spent in prison. Psychopaths typically do not want to be seen as "crazy," or be sent to a psychiatric hospital for a stay that could exceed a prison term.

Criminal behavior while in a psychotic or drug-induced state needs to be distinguished from antisocial personality behavior. The conclusion of my evaluation of Billy would be used as a basis for whether he would go to prison or receive psychiatric treatment.

My inquiry also had to answer if Billy might be malingering? Malingerers are generally not psychopaths (although psychopaths are known to malinger): malingerers do not have a history dating back to adolescence that includes illegal behaviors and acts of cruelty; malingering emerges later when an illness might provide a useful strategy to elude responsibility or elicit special treatment. On the inpatient unit, time itself would help to answer this question. It is really hard to pretend to be mentally ill for days; doing so for weeks, or even months, is a feat few can master. Billy would be under constant surveillance for months: he had no place to hide. But as time passed, Billy remained lost in his internal preoccupations, full of fears and fantasies. He was not gaming us, he was too ill to play the game.

After weeks of meeting daily, Billy began to speak more freely. I heard about his alcoholic father, a mechanic who could not hold a job, who beat Billy. He beat Billy's mother, too, sometimes in front of their son. Billy said he had trouble learning to read and could not concentrate. He occasionally skipped school, but if he was caught, his father would beat him, so he usually went to school but daydreamed about war movies or cowboy shows on TV. He failed at school but was moved on from grade to grade. He ultimately graduated but was barely able to read.

Billy had been a loner. He started drinking and smoking cigarettes when he was about 13 and progressed to drinking almost every day, often heavily, by the time he entered the service. He told me that it did not make a difference to him whether he had sex with a girl or a boy or later with a man or a woman. He told me about his daily use of hashish, opium, and anything else he could get once he landed in Vietnam. He blamed his sergeant for talking him into stealing from the bodies.

Finally, he began to tell me about the voices he heard in Vietnam -- voices that persecuted and humiliated him. These voices still haunted him, he said, adding that now he had nightly dreams of the fields, full of death, which he had patrolled.

One day, I asked Billy about the day he shot himself. He said:

We were caught because some of the guys were flaunting the loot. I had heard that if you are injured you can get out of going to court, and I sure didn't want no court martial. I got real high, and it's all a blur after that. I kind of remember waking up in the field hospital and later in some hospital in Germany. I felt really weird and the voices were really ragging me. Nothing seemed to help.

Billy was always ready to talk with me, although he spent little time with anyone else on the ward. In the dayroom where we met, he always took a seat that allowed him to see everyone coming and going from the ward. I asked him if he wanted to try a medication that might help with the voices and perhaps with his sleep, and he said "... sure, will it get me high?" I prescribed the antipsychotic perphenazine. Billy said the medication made the voices "fade" but not go away. He remained aloof and suspicious.

I was becoming convinced that Billy had a mental illness, not antisocial personality disorder. A supervisor suggested I read The Mask of Sanity, a classic text, first published in 1941, by Dr Hervey Cleckley, who wrote: "Is it not he himself who is most deeply deceived by his apparent normality?" Cleckley was saying that the psychopath first and foremost deceives himself. It was up to doctors to answer the diagnostic dilemma of whether a person is feigning illness to escape responsibility or whether he is mentally ill -- because the psychopath surely would not know (or tell).

Billy had attracted attention among the university faculty. I was asked to present his case at Psychiatric Grand Rounds, a medical educational ritual that began at Johns Hopkins in the late 19th C. But Billy would not be paraded before dozens of professional onlookers, as was the custom in medicine, but rather in psychiatry his story and the questions he presented would be presented and debated. I worked hard on my presentation and put together as much of his history as I could muster to stimulate the discussion.

Billy did not easily fit within any one diagnostic category because he displayed a combination of traumatic, drug-related, and psychotic features. In fact, as many studies today have demonstrated, people with mental illness are more likely to have a comorbid substance use disorder than not, and the converse is just as true: people who abuse drugs and alcohol are more likely to have a mental disorder than not. However, back in 1971, their common co-occurrence was not yet recognized. Nor did we know then that unless both disorders are simultaneously and effectively treated there would be little chance of recovery from either.

On the day of the Grand Rounds, I put on a fresh, short white coat denoting my novice station among the professors, junior faculty, and senior residents. The long, narrow auditorium in the medical center building had a podium and rows of chairs that could seat about 100. The room was full. The department chairman called the Rounds to order and said we had a diagnostic dilemma and that our conclusions would be instrumental to the patient's future -- namely, prison or hospital. It was an era when feelings about the Vietnam War were ablaze. We were seeing the casualties of war mount not just on television but in the wards of our hospitals and local communities.

In my presentation, I told a story of a young man whose shooting off his finger was not a single or simple measure of him or his illness. I recounted Billy's early cognitive and relationship problems, his victimization by his father, and his progressive use of alcohol dating back to his early adolescence. As a youth, he had petty antisocial behaviors, such as stealing candy or soda. His sexuality was "undifferentiated" in that it did not matter with whom he was sexually engaged, what mattered was what he called "getting off." His daytime fantasies were principally aggressive, in which he was the perpetrator of violence; but his dreams repeatedly revealed him to be the victim of others. I emphasized the symptoms of serious mental illness, namely hallucinations and paranoia, and his progressive retreat from the world of others, leaving him isolated and alone.

His self-inflicted gunshot wound was purposeful, even if oiled by an abundance of disinhibiting drugs. It was also, as I proposed, an overdetermined act: it was the combined product of his aggressiveness, impulsiveness, self-loathing and a need to punish himself, and a strategy to escape a grim and, for him, unbearable military fate. That was the psychological beauty and economy, so to speak, of the act: it served many purposes. He was a man fighting for his emotional survival; this was no conventional war and he no conventional soldier (if there is such a person).

I had searched medical history books for a diagnosis I could offer that might befit Billy. I found one, dating back almost a century: "Constitutional Psychopathic Inferior, With Psychosis." What the term depicted, in an antiquated way, was a person born with a defect of constitution or character that left him disposed to psychopathic behaviors (e.g., stealing or violating social norms) but who also showed clear and persistent evidence of psychosis. Today Billy would likely carry multiple diagnoses including psychosis (perhaps schizophrenia), a co-occurring substance use disorder, and PTSD.

When done with my presentation, the floor erupted with questions and comments. "Did I consider that he might have sustained a head injuring from early childhood abuse or concussive blows in Vietnam?" asked a professor at the VA who had seen more soldiers returning from Southeast Asia than anyone else. Another asked "How could I dismiss the theft and calculated manipulation to avoid punishment that would earmark him as a psychopath?" Well, I hadn't: I tried to put Billy's behaviors in perspective rank order the conditions I thought the most representative of my patient.

One of the professors, a well-known social critic of psychiatry, deemed the whole business of searching for a diagnosis a form of "cultural delusion" we were all swept up in, since, after all, mental illness was a "myth." Another asked if we appreciated that the discussion that day was an ironic metaphor about "the war"? He was saying that we were discussing a war that had no moral footing so it was not the patient who suffered from antisocial behavior but our country, which was paying the price for its actions in the court of public opinion, at home and abroad.

This was what I loved about psychiatry. The discussion was not only about organs and physiological processes, as it would be in medicine, neurology, or orthopedics; psychiatry was as at home with psychology, sociology, and ethics as it was with the practice of medicine.

After near to a half hour of lively discussion replete with varied and contradictory ideas, two senior professors took control of the discussion. Neither saw Billy as a psychopath. In their view, Billy was mentally ill and had had signs of psychotic illness since late adolescence -- a typical time for the onset for serious mental illness.

The emotional and physical abuse Billy received as a child affected his capacity to trust. It also produced the (now documented) changes to the brain's anatomy and physiology that trauma can induce. His abuse of alcohol and drugs disinhibited antisocial conduct, probably also contributed to brain damage, and unleashed his psychotic symptoms. The professors recommended that Billy receive treatment through the VA (and later from community-based services) for what they considered primarily mental disorders and what we now call the invisible (psychological) wounds of war.

The Rounds ended. Faculty and students dispersed. I had survived my first professional presentation; more important, I thought, was that I had obtained the support needed to keep Billy in the hospital, in treatment. I believed he was a survivor; in his unique, troubled way he had endured the catastrophic circumstances of his life and of South East Asia. He had taken matters into his own hands, so to speak, and then found help in an improbable intern on rotation in a local VA hospital.

As months passed, Billy remained in his shell. I was witnessing the entrenchment of a severe and persistent mental illness (and today, I wonder as well, the institutional effects of long term hospitalization). He was more preoccupied with his hallucinations and more guarded and paranoid. There were days he would not leave his room, and when he did, he sat vigilant in the dayroom. Medications did not help much with the paranoia or his withdrawal. He also was showing features of a chronic psychotic illness with apathy and lack of motivation, difficulty in experiencing pleasure, and a blunted expression and feelings. His face seemed frozen, and any luster that once existed had dimmed from his eyes. He took little care of his hygiene and appearance. He chain-smoked and harbored a nest of secret suspicions.

Billy was not going to be cured any more than someone with a chronic medical illness, such as heart disease, diabetes, or emphysema. He needed long-term treatment and rehabilitation to regain a life, albeit a life limited by mental illness. In the early 1970s, being mentally ill did not carry the same prospect for recovery as it has in recent years.

Billy would be allowed to stay in the hospital and, in time, would be discharged to the community. He was not a menace to society, nor was he a psychopath. He was a sick man who needed treatment. In his own way, he knew that and abided by the rules of medical care by being a responsible patient.

I said goodbye to Billy when my rotation at the VA ended. After almost a year in the hospital, Billy was then discharged to live in a group home for people with mental illness. He was at the beginning of a long journey that would test him and his caregivers' skill and resolve, but he would have a chance to make a life in the community.

Billy taught me more about mental illness than any book or paper I had read or seminar I had attended that year. I had known him for six months and saw the way that serious mental illness can fix its grip on a person and not let go. I also saw a will to live and a determination to recover and make a life despite what some would regard as amongst the worst that fate could deliver. In thieving from the dead and maiming himself, Billy did do something illegal and, for some seemingly incomprehensible, but his just fate became that of a sick man, not an evil one.

Back To The Future

Psychotic illnesses represent a small percent of the mental and substance disorders that afflict our soldiers. Nonpsychotic disorders, such as depression, PTSD, panic disorder, and the abuse of alcohol and drugs, are far more common--and infrequently require hospitalization. Yet depression, PTSD, and drug and alcohol disorders can produce the same desperation and disability as psychotic disorders.

Suicide results from the deadly combination of horrific psychic pain and a conviction that there is no exit; giving up seems almost rational. Drugs and alcohol diminish judgment and fuel impulsivity, serving as great risk factors in self-inflicted wounds and deaths. Suicide among veterans is at the highest it has been, with twenty two (22) Vets dying at their own hands every day, exceeding the numbers dying in combat.

Veterans with mental (and substance use) disorders can be helped to recover and rebuild their lives. Many can avoid disability and contribute to society, as did Chris Kylie before another Vet took his life.

Veterans -- and their families -- need our help to overcome the stigma and barriers to care faced by persons with mental illness. Not only is this the law, it is what we owe our veterans, their families, and our communities. Many courageous Vets, and their families, are telling their story thereby making it a little easier for others to follow in their footsteps of recovery.

While homicide is exceedingly rare, it is occasionally perpetrated by persons with mental illness. Forensic mental hospitals around the world have patients who have murdered in a psychotic state. The law recognizes that illness, not only badness, can prompt murder. And the law calls for different outcomes for those with psychotic illnesses than for psychopathic killers.

We shall see how a jury judges Eddie Routh.

Private David Lawrence committed murder. There has been no contest about either his having a psychotic disorder or his capacity to understand what he did was wrong when he planned for and shot his prisoner. But the law permitted him to accept a lengthy but not life term of imprisonment.

While prisoners are entitled to proper treatment of medical conditions, including mental illnesses, few prisons provide the level of care needed for a serious mental illness and most are not equipped to manage the worsening behaviors of mental illness that incarceration evokes.

Treatment is what is due our Vets, the sooner the better -- before a tragedy like that which befell Chris Kylie brutalizes everyone involved and leaves its indelible scar.

_____________

An earlier version of this article was published in Psychiatric Times on October 05, 2011.

Dr. Sederer's book for families who have a member with a mental illness is The Family Guide to Mental Health Care (Foreword by Glenn Close) and is now available in paperback.

Dr. Sederer is a psychiatrist and public health physician. The views expressed here are entirely his own. He takes no support from any pharmaceutical or device company.

http://www.askdrlloyd.com -- Follow Lloyd I. Sederer, MD on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/askdrlloyd