Every 14 minutes a person dies of a drug overdose in the United States. This means more than 35,000 deaths every year, exceeding motor vehicle crashes, homicides and suicides!

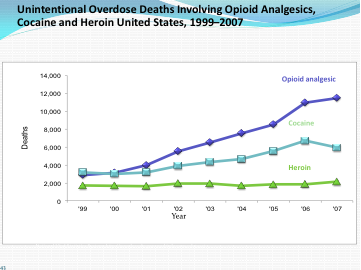

The director of the White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), R. Gil Kerlikowske, a former police and justice official, has called the illegal use of prescription drugs, especially narcotic medications in pill form, the nation's "fastest-growing drug problem." What once dominated the world of overdoses in the U.S., namely heroin, has been eclipsed by the prescription painkillers (see below). These drugs are termed opioid analgesics, referring to substances produced from the opium poppy or manufactured synthetically with the same pain killing effects on the human brain (analgesic means lack of pain).

Where are the drugs coming from? More than 70 percent of those who have abused prescription narcotics got them from a friend's or relative's prescription. In other words, the supplier is no stranger. And the problem starts early: A 2009 national survey done by The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (a federal agency) demonstrated that 1 in 3 youth ages 12 and older began their path to drug abuse by using prescription drugs for non-medical purposes, namely to get high. Teens now report, according to a report by the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, that it is easier to get prescription drugs than beer.

In 2009, hydrocodone (Vicodin™ and generic equivalents) was the most prescribed prescription drug in the U.S. -- twice that of the second most prescribed drug, Lipitor™. Sales of opioids have increased more than six-fold since 1997, as reported by the Drug Enforcement Administration of the US Department of Justice.

We've learned through experience in drug control that police-like interventions of finding bad guys and locking them up doesn't work. Public health approaches stand a far better chance of reducing abuse, saving lives and even saving money. While no single approach works for the diversity of problems that drive this epidemic, there are a number that have proven effective in states that have implemented them, and that have gathered the support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the ONDCP. Some of these involve you.

For You and Your Family:

Getting rid of unused medications: This involves drop boxes, conveniently located so that families can dispose of medications they no longer need, including opioids. Most people do not know what to do with medications they are no longer using and are concerned about flushing them down the toilet. Drop boxes are a simple solution.

A medicine cabinet inventory: This simple form helps individuals and families keep track of medications they have in the home. If you watch your liquor cabinet you surely should watch your medication cabinet. If you keep an inventory you can tell if pills are missing and, if so, this is an opportunity to talk to your children or other family members about prescription drug abuse. It is an alert that you need to protect your family members from gaining access to dangerous medications.

For Professionals and Government Agencies:

Prescription Monitoring Programs: These are programs run by states in which pharmacies supply the state with information on who is prescribing what medications to which patients in what doses. This may sound like surveillance -- and it is. Thirty-three states, including New York, have a prescription monitoring program (PMP) where pharmacies are required to send data to state health departments about controlled substance prescriptions (which include opioids -- and tranquilizers and sedatives as well). This allows state health departments and drug control agencies to pinpoint their education and intervention efforts at doctors and clinics.

Official Prescription Form: Many states now use special prescription pads that are numbered and very difficult to forge. These are so effective that a blank prescription itself has a significant street value, not just the pills themselves.

Educational Resources for Professionals: Doctors and other medical professionals benefit from bulletins, guidelines and training programs (see the work of the NYS agency for alcohol and substance abuse -- www.oasas.ny.gov -- including its Opiates and Addiction Medication Workbook and Guide for Acute Pain Management for Patients Receiving Maintenance Methadone or Buprenorphine Therapy). More work is needed to better educate doctors about how people with chronic pain are best prescribed analgesics in ways that appreciate their suffering while also offering other means of reducing pain than just high doses of narcotics.

Narcan™: This medication is an antidote, given by injection, which immediately reverses the respiratory depression that is typically the cause of death in narcotic overdose deaths. It can be given easily by any bystander. Narcan™ is used as a part of an overall drug abuse strategy called "harm reduction," where instead of "just saying no" there is a recognition that it is important to keep people alive until they themselves can avail themselves of treatment and successfully say no to drugs.

These are a few of the strategies in use and in need of more widespread implementation. The work ahead is not about keeping pain medications from patients in need. It is about good medicine and public health: identifying who needs opioid medications for pain and other disorders, establishing the best practices to meet the needs of these individuals, discovering the service gaps between what people need and what they are getting and promulgating best practices to close this gap (called the "science to practice gap") and monitoring who is doing what needs to be done and intervening in a variety of ways, from education to enforcement, with those who can do better.

Doing all this is hard work. It takes a partnership among patients, families, doctors, clinics, professional associations and government agencies. It takes good communication and sophisticated tracking of what works for whom. It takes ongoing dedication to a needed cause. When those elements of a campaign to reduce opioid abuse and overdose death are in place we will save a lot of lives.

The opinions expressed here are solely my own as a psychiatrist and public health advocate. I receive no support from any pharmaceutical or device company.

Visit Dr. Sederer's website at for questions you want answered, reviews, commentary and stories.