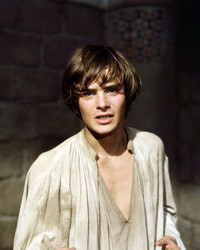

Valentine's Day-timed Romeo and Juliet tie-ins can be found everywhere, from the upper-middle-brow NEH-funded PBS series Shakespeare Uncovered, which premiers a Joseph Fiennes-hosted episode on Romeo and Juliet on February 13th, to San Francisco's campy Castro Theatre, where the fare for February 14th is a "Marc Huestis presents" screening of the 1968 Franco Zeffirelli film, complete with an in-person appearance by Leonard Whiting, Zeffirelli's Romeo (and heartthrob of an entire generation of gay men). It's timely proof that Romeo and Juliet remains the world's favorite love story.

But this popularity is hardly a testament to the lasting power of Renaissance high culture. Rather, it reflects how we cling to the idea of a love story that we've collectively projected onto Romeo and Juliet, while ignoring the most fascinating, troubling and cautionary aspects of Shakespeare's play. Because if you believe Romeo and Juliet is a romantic tale about teens in true love who are kept apart by feuding parents, you've completely missed the point.

Romeo is a lascivious creep you wouldn't want dating your 13-year-old daughter.

Romeo meets Juliet after donning a disguise and sneaking uninvited into a party thrown by her father. This bit of trickery is necessitated by the enmity between their families. But our attachment to the idea of Romeo and Juliet as star-crossed lovers obscures the fact that Romeo sneaks in to seduce another member of the Capulet clan, Juliet's cousin Rosaline. Despite Rosaline's vow to remain chaste, Romeo confides to his buddies Benvolio and Mercutio that he even offered to "ope her lap to saint-seducing gold" -- a poetic way to say he tried to pay Rosaline to let him deflower her.

Upon seeing Juliet, Romeo fickly turns his attention to her. But he remains a sordid character. Just one hour after marrying Juliet, Romeo whines to himself that her "beauty hath made me effeminate," and proceeds to prove his manhood by stabbing her other cousin, Tybalt, to death.

Juliet's father isn't a cruel villain trying to force his daughter into an unhappily-ever-after marriage.

For much of the play, Lord Capulet is the character most in line with our modern ideas about romance. During the not-so-good-old days of the 14th century in which Romeo and Juliet is set, marriage was a means for wealthy Italian families to form political and business alliances. Typically, a father decided whom his daughter should marry. But Lord Capulet doesn't want to exercise this option.

We learn this when Paris -- a nephew to the city's ruling prince and thus exactly the sort of well-connected son-in-law any paterfamilias should want -- presses Lord Capulet to give him Juliet in marriage. Lord Capulet responds, "woo her, gentle Paris, get her heart/ My will to her consent is but a part/ An she agree, within her scope of choice / Lies my consent and fair according voice." In other words, he says Juliet should get to decide the not-so-unimportant question of whom she'll marry.

So why doesn't he let Juliet marry Romeo? Because she weds Romeo in secret, never giving her father a chance to accept him as a viable suitor. Which he may well have done, given that back when Romeo crashed the Capulet party, Lord Capulet protected him. Tybalt (not yet dead) recognized Romeo and was ready to show the interloper what happens when you don't RSVP properly -- until Lord Capulet stopped him. An unfortunate choice for Tybalt's long-term health outcomes, but also an indication that Lord Capulet might have been amenable to Romeo courting his daughter.

Later in the play, Lord Capulet does say he'll make Juliet marry Paris. But by that point, Tybalt is dead, which Lord Capulet thinks is the reason Juliet has become so unhappy. He vows he'll cheer her up with a handsome, noble husband. It's not exactly a Hallmark card and a sympathy floral arrangement, but again, Lord Capulet has no idea she's ever met Romeo, let alone clandestinely married him.

Romeo and Juliet only became a teen love-story in the 20th century.

Although dialogue in the play reveals that Juliet is a few weeks shy of her 14th birthday, Shakespeare never tells us Romeo's age. In the era in which the play takes place, men usually married later in life, to much younger wives, making it likely that Romeo is at least twice as old as Juliet. So why do we think of Romeo and Juliet as star-crossed teenage lovers?

Blame an odd combination of post-WWII social science and the pool at the Beverly Hills Hotel. That's where composer Leonard Bernstein and playwright Arthur Laurents dreamed up a Latino-themed musical version of Shakespeare's love story, resulting in West Side Story's Puerto Rican Sharks and their rivals, the Jets. But the 1957 play drew as much on the sociological mindset reflected in Rebel Without a Cause as it did on Romeo and Juliet, with a libretto, lyrics, and even choreography all influenced by then-popular social science regarding "problems" like immigration and juvenile delinquency.

A decade later, 1960s youth culture inspired Zeffirelli's Summer of Love-infused film, in which Juliet and Romeo are the ultimate teens rebelling against square parents. By the time Baz Luhrmann took up the mantle (or the doublet) in 1996, the idealization of youth culture -- and the romanticizing of the doomed lovers--had become an undeniable part of the story. Luhrmann even gives the lovers one final scene together in the tomb, both awake before they die in each other's arms. If only Shakespeare had thought of that.

Romeo and Juliet weren't even the stars of the show.

Although fans of Whiting and Olivia Hussey, of Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes, or of Fiennes and Gwyneth Paltrow might not believe it, the plum roles that generations of actors wanted to play, and generations of theater-goers were turning out to see, were actually Mercutio and the nurse, both of whom are unrepentant scene-stealers.

In Juliet's first scene, she has only eight lines; the nurse, has more than 60. Overall, Shakespeare gave the nurse more lines than any other character in the play besides Romeo or Juliet, and Juliet actually speaks more of her lines to the nurse than to Romeo. These days the nurse is generally written off as comic relief, but in her first scene, she alludes to the heart-rendering loss of her own child, foreshadowing the deaths that end the play. Samuel Johnson praised the complexity of the nurse's character in his annotated edition of Shakespeare, and Jim Carter, aka the future Mr. Carson on Downton Abbey, gave her top billing in Shakespeare in Love. I found Juliet's nurse so compelling, I wrote an entire novel about her.

As for Mercutio, in his most famous speeches he mocks lovesick Romeo, reminding the audience of the folly of Romeo's fickle infatuations. (In Mercutio's other speeches, he is mocking everybody else.) He proves so appealingly snide that there's even an apocryphal tradition -- promoted by John Dryden -- that Shakespeare declared he was obliged to kill Mercutio in the third act, or be killed by him. But Mercutio speaks with more perspicacity regarding humanity than any other character in the play. Ultimately, what distinguishes both the nurse and Mercutio is the way they balance the comic and the tragic, making them far more deeply drawn than the eponymous young lovers.

Double suicide is not the best basis for a rom-com.

It sounds a little obvious when you say it this way: A story in which a 13-year-old girl is seduced by a deceiving cad who turns out to be a killer, then is convinced by a prevaricating priest to fake her own death, and finally ends up committing suicide for real -- this should not be a global model of a love story.

Romeo and Juliet is, after all, one of Shakespeare's tragedies (as compared to Much Ado About Nothing, a comedy containing a more successful scheme involving a faked death, resulting in two happily wedded couples). A convention of tragedy is that the characters who die should do so in a way that transforms the ones who live. If this were true for Romeo and Juliet, Lord Capulet and Lord Montague would learn their lesson by the end of the play and, moved by their children's deaths, put aside their "ancient grudge."

But the tragedy of this play extends beyond the title characters, in a way that suggests that misreading Romeo and Juliet, and thus Romeo and Juliet, is irresistible, and perhaps inevitable. Even as they stand over a pile of lifeless bodies in the final scene, Capulet and Montague revert to the same competitive behavior that prolonged their feud. Invited to take Capulet's hand to signal a newfound peace, Montague instead vows to build a gold statue of Juliet, his erstwhile enemy's daughter -- a show of his own wealth that incites Capulet to say he'll erect a matching statue of Romeo. Still eager to engage in this weird one-upmanship masquerading as benevolence, they miss the potentially redemptive point of the play.

And so, it seems, do we. Helped along by a legacy of 20th-century pop culture and our less-than-insightful high school readings of Romeo and Juliet, we continue to indulge our persistent desire to romanticize a play that might be Shakespeare's greatest critique of romanticizing something (and someone) that really isn't that romantic after all.