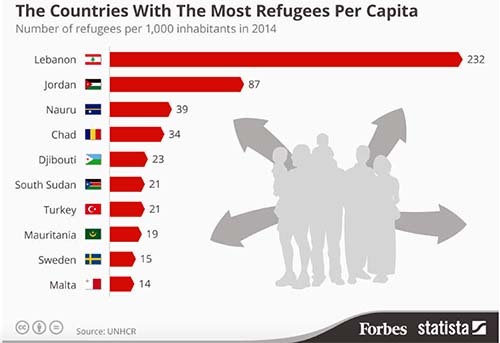

If there is one country where migration is a meaningful crisis story it is Lebanon, which, according to Forbes-Statista/UNHCR, has the most refugees per 1,000 inhabitants -- 257 in mid-2014.

Lebanon's population is estimated at 4.5 million. Syrian refugees are estimated at anywhere from 1.3 to 1.5 million, with unregistered numbers approaching 2 million, according to some studies.

But the very definition of a refugee, an asylum seeker or a migrant, takes on more than the usual connotations in a country burdened by a history of sectarianism, political and economic uncertainty, feudal patronage, and more.

The Bloomberg View offers a perspective on who is a refugee, according to the 1951 UN convention and a 1967 protocol, as well as the principle that countries can't send refugees away once they arrive, also known as non-refoulement.

However, Lebanon is not a signatory to the convention, so its situation is both murky and untenable - more so when media are covering a crisis well beyond the country's capacity.

Dr. Guita Hourani, Director of the Lebanese Emigration Research Center and Assistant Professor at Notre Dame University's Faculty of Law and Political Science, wrote in an email interview:

As told by the media in Lebanon, various pressures shape the 'migration' story, including highlighting the calamity of displacement and its humanitarian consequences, especially at the onset of the crisis.

However, as settlement occurred and years passed without any prospect of return, resettlement in a third country and inflow of assistance to the host community and country, the story began to recount the impact of the crisis in economic, social, and demographic terms.

The latter was also emphasized as the 'takfiris' (Islamic fundamentalists who denounce the 'others' as apostates) began to infiltrate vulnerable refugee communities.

The story changed, too, to reflect the economic recession and increased inflation - due in part to the protracted Syrian crisis, the involvement of Hezbollah in the fighting in Syria, and the lack of consensus on electing a president for Lebanon, among other issues.

She added that Lebanese and foreign media coverage had contributed to the stereotyping of both communities - refugee and host.

In June 2015, the daily Assafir ran a telling headline: "The Patriation/Naturalization Choice: Syrians or Palestinians?" in reference to the hundreds of thousands of refugees and asylum seekers who have flooded in since the Syrian conflict erupted in 2011 and the earlier creation of the state of Israel in 1948, leading to successive waves of people from neighboring countries and what their presence has meant to the already-sensitive issue of "sectarian balance."

An alarmist article entitled "Before Lebanon Becomes a Depot for War Refugees" in the daily Al Joumhouriya on July 12, 2015 shed light on the crisis, noting that no country has had to face refugee numbers that almost match its population.

It quoted Rock-Antoine Mehanna, Dean of the Business School at Beirut's La Sagesse University, pointing to an internal economic cycle within the main Lebanese cycle, when Syrian merchants buy products in Syria then sell them to other Syrian merchants in Lebanon who, in turn, sell them to Syrian laborers in Lebanon, thereby creating an economic crisis.

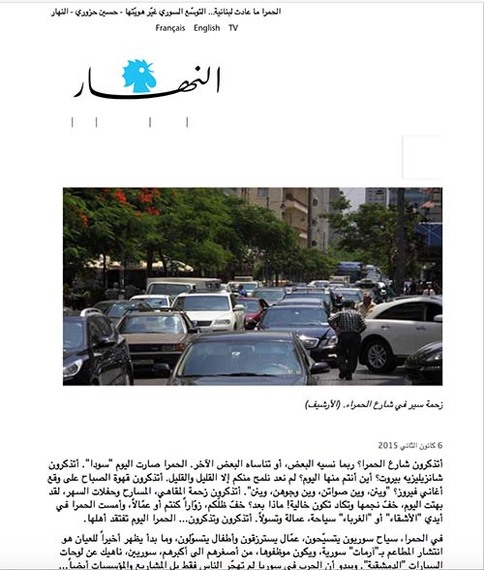

In January 2015, the daily Annahar published a diatribe by Hussein Hazoury who said Hamra Street, Beirut's one-time Champs Elysées, had changed color from "Hamra" (red) to "sawda" (black) with the unregulated influx of (dark-skinned) Syrians.

He complained that the street had lost its charm, that the Syrian presence had changed Hamra's demography, and that restaurant owners were decrying the proliferation of cheap Syrian labor and competition from Syrian eateries.

The comments caused such a backlash on social media, charging Annahar with racism, that its administration had to publish a clarification hours later saying the commentary didn't reflect the paper's editorial line or values and that the writer had just expressed his personal observations.

However, there are stories in print, broadcast and online media that show sympathy for refugees and displaced people and that focus on the humanitarian aspects of the crisis.

A case in point is the story of Fares Khodor, a friendly 11-year-old Syrian boy who in 2015 sold flowers on the streets of the Hamra district and who one day on his way back home was killed by the anti-regime coalition's air campaign, according to news reports.

His death triggered a social media frenzy of sympathy, but it also led to unsubstantiated reports and questionable pictures of a boy resembling Fares who was said to have carried out a suicide attack in Syria.

For Diana Moukalled, a television journalist, documentary producer, columnist and women's advocate, Lebanese media contribute to hate-speech against refugees, displaced persons and asylum seekers in news stories, comments and columns.

"Media usually deal with refugees as a block and not as individual stories," she said. "There is some good coverage, but that does not represent the mainstream media."

Asked whether the pressure of time, competition among Lebanese media and sources of information affected coverage, Moukalled replied: "The time factor is minimal. But there is a lack of professional and ethical will to cover these issues fairly. Again, there are really good reports sometimes but the main approach is negative and full of stereotyping and labeling."

The Maharat Foundation released an invaluable study in August 2015 on Lebanese media's coverage of mostly Syrian and Palestinian refugees, migrants, and displaced persons.

The 58-page project, Monitoring Racism in Lebanese Media: Representations of "The Syrian" and "The Palestinian" in News Coverage, takes a critical look at how these two communities are portrayed. It analyzed coverage in newspapers, television, radio and news websites.

The study said the presence of Syrian and Palestinian refugees had long been a factor of division and conflict among Lebanese.

That has translated into the political and media discourse, which becomes fodder for scaremongering against strangers and hate-speech that plays on identity, demography, everyday life and national security issues.

Media, understandably, jump on headline-grabbing statements by officials calling for radical solutions.

"Some political discourses call for repatriation of refugees," said LBCI TV correspondent Yazbek Wehbe. "Media cover these statements and activities about refugees and sometimes disseminate pejorative terms used by those they report, but it's unseemly."

Wehbe explained that no intentional anti-refugee stance by the media existed, nor did any systematic editorial policy about such coverage.

To help mitigate the problem, the Samir Kassir Foundation (SKEYES) conducted a workshop on coverage of the refugee crisis in February 2014. The aim was to highlight the role of NGOs in helping refugees and the definition of human rights journalism that can move public opinion to action.

In mid-June, 2015, Amnesty International launched its world report from Lebanon entitled The Global Refugee Crisis: A Conspiracy of Neglect. Amnesty also released a sister publication Lebanon: Pushed to the Edge: Syrian Refugees Face Increased Restrictions in Lebanon since the country is considered the epicenter of the Syrian refugee crisis.

In their contribution to the book "In Line with the Divine: The Struggle for Gender Equality in Lebanon," authors Rouba El Helou and Maria Bou Zeid examine the absence of women in the refugee picture.

In the chapter "Dissonance and Decorousness: Missing Images of Syrian Women Refugees in the Lebanese Media," an introductory summary explains the missing media components:

Thus far Lebanese media coverage has centered on the impact of the displacement of Syrian women refugees, especially their need for humanitarian aid, their experiences of rape and torture, or sexual harassment during settlement. This partial coverage has given a one‐sided perception of Syrian women refugees suffering from forced migration.

Media reports have failed to highlight how these women have become active in handling the organization and distribution of aid and how they are facilitating their families' lives to whatever extent is feasible.

The reports also have ignored the fact that Syrian women use their creativity to provide their families with basic needs through establishing and running small businesses or working for Lebanese employers.

This is a summary of the chapter Lebanon: Media Put Humanity in the Picture as Refugee Crisis Takes Hold Magda Abu-Fadil wrote in Moving Stories: International Review of How Media Cover Migration published by the Ethical Journalism Network and edited by Aidan White.