What an eye-catching headline!

The tarboush, a/k/a the fez of Middle Eastern and Arab lore, was pegged as the root cause of the recent flap between Egypt and Turkey.

The powers-that-be in Cairo are on the wrong side of Ankara's grand poobahs, yet again.

The reason: the Egyptian military deposed the elected Muslim Brotherhood president Mohammad Morsi on July 3 and replaced him and his cohorts with an interim secularist government until new elections are held.

Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan and his Islamist government felt a kinship with Morsi and his supporters.

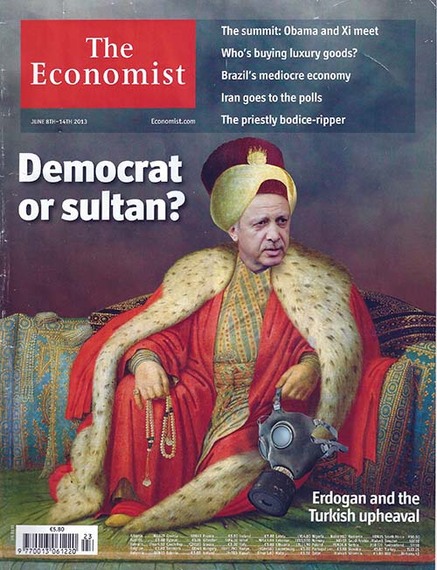

Erdogan, accused by domestic and regional detractors of trying to revive the old Ottoman Empire and appointing himself as the new sultan, with an eye to bolstering ties with like-minded Sunni Islamists, also has a major aversion to the highly secular Turkish military, which he's afraid is out to topple him.

The sultan's image was magnified by a June cover story in The Economist as Erdogan cracked down on home grown protesters against his government.

Erdogan "Democrat or sultan?" on The Economist cover (Abu-Fadil)

According to an article this week in Egypt's Al Masry Al Youm newspaper, the falling out dates back to 1932 when Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, founder of modern-day Turkey, reportedly insulted the Egyptian ambassador at a major reception.

Ataturk, whose revolution did away with vestiges of Ottoman rulers, including tarboushes, apparently spotted envoy Abdel Malek Hamza wearing a fez at the 500-person dinner-dance marking Turkey's national day when all other men were bare-headed, and told the ambassador to remove it.

The ambassador complied, but left the reception soon thereafter and was later withdrawn from Turkey, causing a diplomatic incident.

A man without his tarboush was considered almost naked and probably uncouth in pre-1952 revolution Egypt.

The article's author aimed to draw parallels between Ataturk's domineering attitude and Erdogan's domineering and negative approach towards Egypt's military.

Many Arabs view it as Turkey's (pre- and post-Ottoman era) patronizing stance in the Middle East region.

So where does that leave the tarboush?

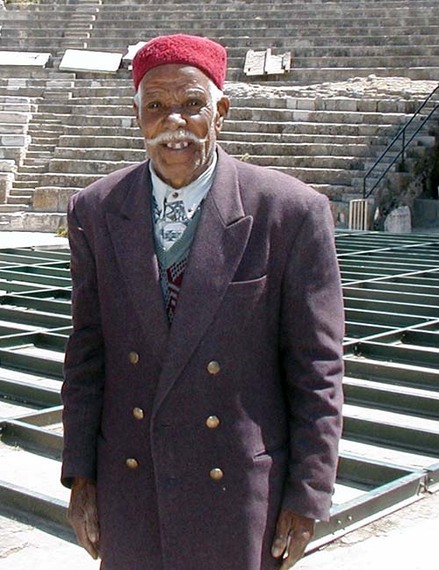

Today men donning the red felt hat with a black tassel on Cairo's over-crowded streets or in government offices would be considered oddities or throwbacks to the days when Egypt was ruled by foreigners.

Tarboush makers, like other artisans, have been a dying breed for years.

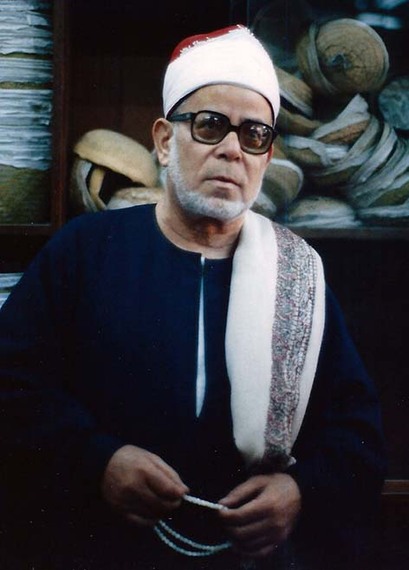

I remember visiting a shop where a man turned out about eight cylindrical, flat-topped handcrafted hats a day, a trade he learned from his father and grandfather before him.

He told me the tarboush dated back to the Ottomans when Egypt was a kingdom and all the royal guards, police and army troops and officers wore it but that only Muslim clergymen, a few surviving Egyptian royalists and members of older Turkish families continued to don it, as did actors playing period roles in feature films and on television.

Interestingly, even after the revolution, most doormen outside Cairo's ritzier hotels and restaurants wore braided uniforms and colorful costumes complemented by fezzes.

Muslims and Christians alike once favored the tarboush in Egypt but after King Farouk was ousted in 1952 it became associated with his discredited monarchy as well as with an uncomfortable era of British domination.

In North Africa, Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian and Libyan men still wear the tarboush. It is also associated with the city of Fez in Morocco while some historians trace it back originally to Greece.

Most of the fezzes I saw were made from various shades of red felt and wool, although some were fashioned in black.

The material was cut by hand and steamed onto a braided straw core that formed the hat's skeleton.

The core was then fitted onto a mold - three men's sizes and a smaller child's size - and covered by a heavy metal press with protruding wooden handles that secured the shape.

The tarboush maker then screwed down a brass weight from the press before spraying his creation with starch to give it a rigid and upright appearance.

A satin lining was then fitted inside the hat and a black zirr (tassel) was attached to a short red tail on top of the hat after it had been steamed into its final shape.

The once ubiquitous fez is a novelty today sought by souvenir-buying tourists in Cairo.

Who would have thought it would, once again, be referred to as the source of rocky ties between Egypt and Turkey?