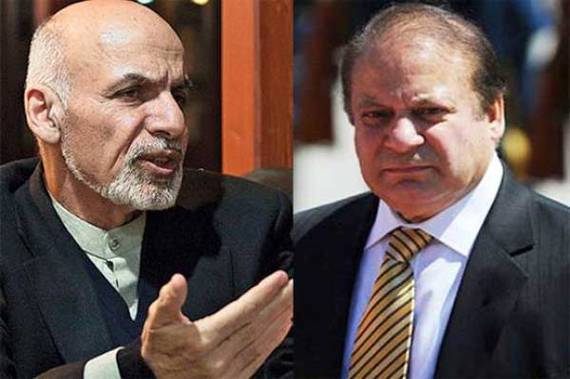

Photo Source: Sama TV, Pakistan

Tensions between the Pakistani and the Afghan governments are gradually coming out in public following the terrorist attack on the Bacha Khan University by the Taliban on January 20th. Although Pakistan's army chief General Raheel Sharif had called the Afghan President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah to seek their help in tracing the perpetrators of "this heinous act" and bringing them to justice, the Pakistani authorities had cautioned that their communication with the Afghan officials did not mean that Islamabad suspected Kabul's official involvement in the attack. On Monday, Pakistan's Foreign Office summoned Syed Abdul Nasir Yousafi, Afghanistan's Islamabad-based Charge d'Affaires and urged his government "to take action against the perpetrators of this heinous act of terrorism and extend cooperation to Pakistani authorities to bring them to justice at the earliest possible."

Afghan complaints against attacks by the Pakistan-based-and-sponsored Taliban are legitimate but they are already so widely known that they no longer excite the media. Remember former President Hamid Karzai publicly cry in 2006 while expressing utter helplessness that terrorists coming from Pakistan [and also NATO strikes] were killing his country's children?

Ghani has equally been upset with Pakistan. Last summer, he criticized Islamabad for its failure to curb terrorist attacks. "We hoped for peace, but war is declared against us from Pakistani territory," he said at a news conference as, Wall Street Journal reported, "Afghanistan's top security officials stood behind him in a show of support."

Many within the Afghan government question Ghani's toughness toward Pakistan. For instance, last month, Rahmatullah Nabil, the head of National Directorate of Security, quit his job citing "lack of agreement on policy matters" with President Ghani. Apparently, he was upset with Ghani's visit to Islamabad to discuss economic cooperation with Pakistan, a country many Afghans blame for supporting the Taliban that have destroyed and divided the Afghan society.

"Our innocent countrymen were being martyred and beheaded in Kandahar airfield at the moment when [Pakistan] Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif once again said Afghanistan's enemy is Pakistan's enemy," Al-Jazeera quoted a Facebook post by the enraged intelligence chief as he quit his job in protest.

Contrary to the Afghans, it is relatively new for the Pakistanis to publicly show desperation and helplessness toward the Taliban who have found safe sanctuaries in Afghanistan. The fact that Pakistan's army chief, instead of the prime minister, hastily called Afghanistan's President and Chief Executive, reflects the anguish and helplessness that prevails in Islamabad these days. While Islamabad has always had the ability (but certainly not the will) to utilize military or diplomatic channels to control or quash the so-called "good Taliban" and the "bad Taliban", President Ghani's weak government in Kabul simply does not have the capability to prevent the Taliban from operating inside Afghanistan let alone stopping them from attacking Pakistan.

When they met last month in Rawalpindi on the occasion of the Heart of Asia Conference, Pakistan's General Sharif told Ghani that his country was "committed to work together with Afghanistan on the basis of mutual interest and respect." But, Ghani, in response, reminded him that Pakistan's recent military actions against the Taliban "had created unintended consequences bringing about the displacement of a significant number of militant groups on Afghan soil."

Pakistan faces a dilemma in Afghanistan. Historically, the "good Taliban" [referring to those who do not attack the Pakistani state] and the "bad Taliban" [who attack the Pakistani army and civilians] all mushroomed under the patronage of the country's intelligence agencies. Those focusing on Afghanistan felt deeply betrayed when General Musharraf joined the U.S.-led war against terrorism that not only toppled the Taliban government but also landed several key Taliban leaders in American prisons. My Life with the Taliban, the biography of Taliban's former ambassador to Islamabad, Abdul Salam Zaeef, who was arrested and kept in Guantanamo, explicitly explains the bitterness and sense of betrayal the Taliban feel toward Pakistan. Furthermore, Pakistan is even under pressure to sever ties with the "good Taliban" whom India recently blamed for the January 2nd attack on Pathankot Air Force Station. President Obama, in an interview with the Press Trust of India, reaffirmed the call for Pakistan to take action against all Taliban groups. The President said:

"Pakistan has an opportunity to show that it is serious about delegitimising, disrupting and dismantling terrorist networks. In the region and around the world, there must be zero tolerance for safe havens and terrorists must be brought to justice."

Meanwhile, Pakistan is also getting frustrated with its inability to bring the Taliban back to the negotiation table since the disruption of talks last summer following the disclosure of the news about the death of the Taliban chief Mullah Omar. The more Pakistan shows weakness and frustration, the brighter a future the Taliban will see for themselves in the region hoping that they can once again regain control over Afghanistan and also parts of Pakistan through a renewed insurgency waged from Afghanistan.

Pakistan will have to approach and deal with the Ghani government carefully. Harsh gestures, such as the summoning of the Afghan envoy in Islamabad on Monday, can backfire. Islamabad and Kabul will have to prepare for a long battle against various Islamic extremist groups (such as the Taliban and the regional brand of the Islamic State). The longer the two governments remain patient with and helpful to each other, the better they can avert a fresh violent wave of radical Islamic movements in the Af-Pak region.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please make a donation to help me re-launch the non-profit online newspaper, The Baloch Hal. To make a donation, please click here.