It has taken me quite a while to get this post up--I saw the show nearly a month ago--but that's not to say that it wasn't significant or I had nothing to say about it. In fact, quite the opposite. These photographs--so much more affective and beguiling, magical, honest, breathtaking, and complex in person than when reproduced in books (though still beautiful then)--have lingered in my head since I saw them in the flesh. At the Photographers' Gallery through September 19, the show is beautifully hung--intimate and quiet, dark and mysterious, giving way the perfect environment for Mann's ethereal quality. In a separate closet-size room the documentary What Remains: The Life and Work of Sally Mann (2005) plays. I watched about 40 minutes of it--Mann and her husband Larry Mann, who she photographed over the period of six years while he was struggling with muscular dystrophy in her 2009 series "Proud Flesh" (a series that was sadly left out of this show), watched the birds soar and their dogs frolicking in the acres of open land they have in rural Virginia.

At Warm Springs, 1991, from the series "Immediate Family"

© Sally Mann. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

"Unless you photograph what you love you're not going to make good art," she said. And this mother's first love is her children, who she captured running feral and in sometimes quite obviously set up poses, other times honest and innocent and serene. One of my favorite photographs in this show was At Warm Springs, 1991, of her daughter Virginia, her eyes closed, and her face floating above the water's surface, her curly locks resting on top of the water, Medusa-like or saint-like, whichever you prefer. It evokes a Botticelli painting--and disregarding the unending argument surrounding Mann's work and the controversy in taking (and profiting from) nude or potentially eroticized images of her children, or anything else Mann has been criticized for--this photograph, sans nudity, shows the honesty and innocence of childhood and all the complexities that form around this pure nature.

Candy Cigarette, 1989, from "Immediate Family"

© Sally Mann. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

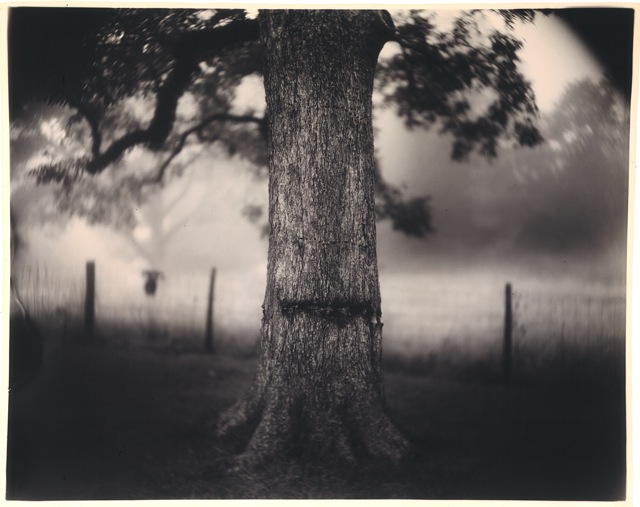

Scarred Tree, 1996, from the series "Deep South"

© Sally Mann. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

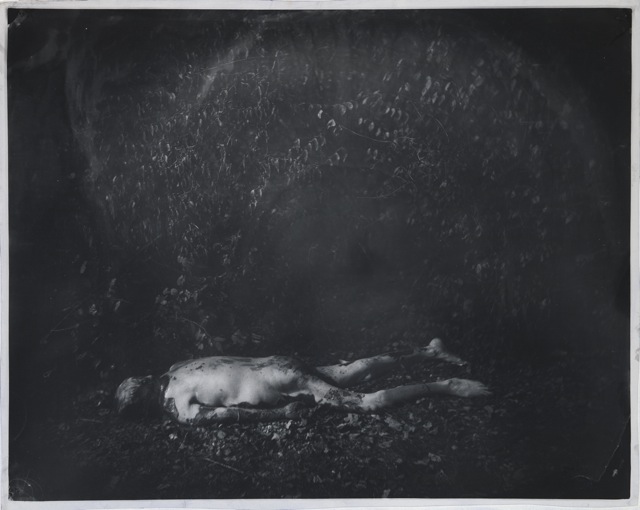

Mann's series "Deep South" (1996-98) documents sites of imaginably gruesome battle scenes that took place during the American Civil War. The scenes--taken using wet plate collodion negatives, a process that dates back to 19th century photography, when chemical photography began--feel suspended in time, ghostly and eerie both in aesthetic and subject matter. And this preoccupation with death and dying is faced directly in an even more disturbing series titled "What Remains" (2000-04), where Mann was given access to the University of Tennessee Forensic Anthropology Center. Here, bodies that have been donated to science are left outside in the wood to decompose. The graininess and dreaminess of photographs make them accessible, seemingly representational, like a painting or drawing. This nature gives us access to them: while my brain was telling me that these were real bodies, my eyes believed that they were representations.

Untitled WR Pa 59, 2001, from the series "What Remains"

© Sally Mann. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

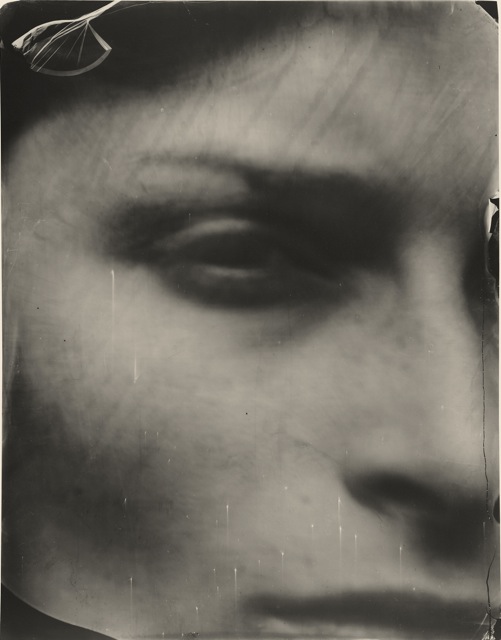

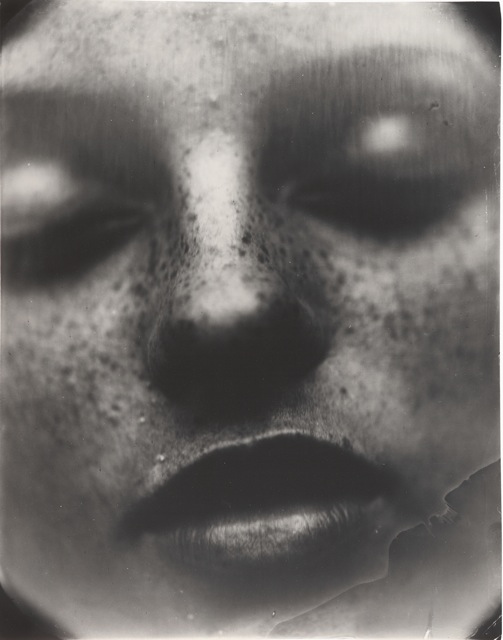

There is a serendipitous aspect to Mann's work. She explains in the documentary that she loves the unexpected, miraculous, that transformed by some hand other than her own. "I really welcome those interventions," she says. "Unlike Proust," Mann said, she prays for the "Angel of Uncertainty to visit [her] plate." She loves the flaws in the negatives and the unexpected aberrations they contribute to the print. She said "I'm so worried that I'm going to perfect this technique some day." Yes, there's a romantic and idealized quality to all this. Inevitably she is still confined by the physical format of the negative in the dark room, but that uncertainty she speaks about and the unrestrained nature of her subjects--her children acting as children do, nature taking its course, and time moving around the clock and through the years--make for a fantasy-like world meets the soft-blow of reality. And it's this dichotomy of real and not real, mortal and immortal, that makes her work so powerful.

"The Family and the Land" Sally Mann, through 19 September 2010, Photographers' Gallery London

Jessie #10, 2004, from the series "Faces"

© Sally Mann. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

Virginia #42, 2004, from "Faces"

© Sally Mann. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery