As the post-mortems arrive to determine the cause of death for Australia's carbon tax, a couple of questions emerge:

Why did this happen?

What lessons can we learn?

The answer to the first question is fairly simple: A politician - Julia Gillard - promised she wouldn't tax carbon, and then she broke that promise. This happened because her Labor Party needed to form a coalition government with the Green Party. The price the Greens demanded for that alliance was a carbon tax, and so she acquiesced.

Extenuating circumstances? Certainly. Do voters give a rip about extenuating circumstances? Usually not. Just ask George Bush Sr., famous for his "Read my lips: No new taxes" statement that came back to bite him in the 1992 election against Bill Clinton.

Add to this toxic backdrop the bitter rivalry within the Labor Party between Gillard and Kevin Rudd - who replaced Gillard as Prime Minister in June of 2013 - and the carbon tax didn't stand a chance of surviving the next election.

Australia's carbon tax, though, was a victim of inept politics, not bad policy. After only 9 months of implementation, the tax was doing what it was supposed to do. Greenhouse gas emissions from electrical generation fell by 5.4 percent and electricity from clean sources jumped 28 percent.

Still, there were flaws in the design of Australia's carbon tax that, if corrected, would have made it more effective and more popular. As proponents for action on global warming regroup Down Under, here are some suggestions to make the carbon tax better and able to garner the political will necessary to survive a volatile electoral landscape:

First of all, apply the tax to the carbon-dioxide content of fossil fuels as they enter the economy. The Australian tax was levied on that nation's 500 largest industrial polluters, mostly in the power sector, on the emissions they produced. This left out large sources of CO2 emissions, like the transportation sector. Taxing coal, oil and gas at the first point of sale has an economy-wide impact on all sources of carbon pollution and achieves greater emissions reductions.

Second, make the carbon tax 100 percent revenue-neutral by returning all of the money to households as a per-capita dividend. By returning ALL the revenue to households, the tax can be gradually increased each year to a level that will have the desired effect on emissions. Returning all revenue equally to all households also ensures that low- and middle-income families will be adequately compensated, and then some, for increased costs associated with the carbon tax.

Third, include border tariffs on imports from nations that don't have equivalent carbon pricing to maintain a level playing field for businesses and discourage the off-shoring of carbon by companies moving their operations overseas. Revenue from the border tariffs would be used to compensate businesses exporting to nations that don't price carbon. Such tariffs would provide a strong incentive for other nations to implement their own carbon tax. The government in China, I'm sure, would much rather see carbon tax revenue from their country's businesses going into their own national treasury instead of somewhere else.

So, after making these adjustments to the carbon tax - and by not transitioning to a loophole-ridden emissions trading scheme after a few years, as was the case in Australia - what kind of results might we expect to see?

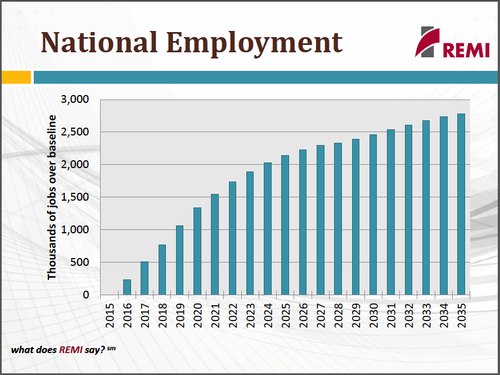

Answers are found in a study released in June from Regional Economic Models, Inc. (REMI) that forecasts the impact in the U.S. of a tax on fossil fuels, starting at $10 per ton of CO2, that rises $10 per ton each year. All revenue is returned to households equally as a monthly payment, and border tariffs are factored in. After 20 years, the REMI study found that emissions dropped 50 percent below 1990 levels, putting the U.S. on track to achieve 80 percent reductions by mid-century.

The exciting revelation of the REMI study, however, was that over 20 years, this revenue-neutral carbon tax would actually add 2.8 million jobs to the American economy. This happens because the considerable revenue from the carbon tax is recycled into the pockets of people most likely to spend the money, creating an economic stimulus.

What this means is that everything being said by carbon tax opponents is wrong. A carbon tax, done the right way, is a job creator, not a job killer.

The REMI study crushes the false and deceptive narrative surrounding the carbon tax that prevents it from gaining traction. As the truth emerges, we can build the public support and the political will, both in Australia and in the U.S., for a policy that not only preserves a livable world for future generations, but also helps our economies thrive.