Kearns' mother couldn't be contained and interrupted the proceedings. "Your honor," she said. "Why is this man lying? The truth is bad enough!"

The truth is sometimes difficult, to be sure, but in the case of this engaging and fast-moving autobiography, it's also hilarious. There's nothing more formidable than a drama queen with legitimate drama on her hands, and the life of talented, alcoholic, HIV-infected, highly theatrical and perpetually horny Michael Kearns has had more peril than an Aaron Spelling series.

Kearns began his career in the midst of the "gay lib" of the 1970s, even if Hollywood was tight-lipped on the topic, and it is that disconnect that pushed the openly gay Kearns into an unintended activist role and confounded his career aspirations.

After a featured role playing the older brother of John-Boy on The Waltons, Kearns' future seemed secure. But test audiences reacted poorly to their scenes together, because they showed the characters away at college. Kearns' character never appeared again. Rumors that he was fired because he was openly gay were untrue but persisted for years.

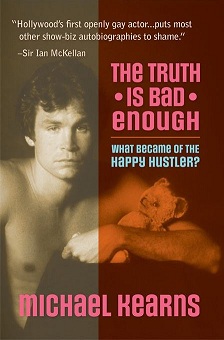

Meanwhile, Kearns had a boyfriend who had written a fictional book called The Happy Hustler, for whose cover image Kearns had modeled. In order to generate book sales, a plan was hatched to present Kearns as the actual Happy Hustler -- the book's author -- and send him on a press tour. Having been banished from Walton's Mountain and still hungry for stardom of some kind, any kind, Kearns agreed to take on the counterfeit persona as a sort of exercise in ongoing performance art.

Keans' drunken appearance as the Happy Hustler (a role he began taking far too literally in his private life) during a 1976 Tom Snyder interview set the stage for both career success and life on a runaway crazy train. Kearns reveled in drug and alcohol abuse as tricks and acting jobs came and went. He slept with celebrities and strangers with equal apathy. His status as the first openly gay actor of note invited curiosity and derision. He agreed to reveal his HIV-positive status for an NBC interview almost as a lark, leading to a period of portraying "the gay guy with AIDS" in a collection of acting gigs.

I was drawn to Kearns' story for the Hollywood gossip, but I kept reading because of something deeper and far more riveting. And it had everything to do with how our lives were fated to overlap.

My own memoir, A Place Like This, travels some of the same West Hollywood streets. I was a bottom-feeder on the Hollywood scene (an expression I should probably withdraw now for its literal inaccuracy), and I never knew Kearns, but we did have a liaison in common: our bedding of the detached and unhappy Rock Hudson. However, let the record show that while Kearns' dalliance was what gay men refer to as "standup sex," mine was brief but at least horizontal. So, um, I win.

Many other famous faces populate the book: gay men, straight men, porn stars of various stripes, and the hypocritically closeted that Kearns, God bless him, outs on his pages with regularity. His characterizations of personalities we thought we knew are enlightening, gentle when need be, and sometimes quite sad.

The funny but famously acerbic Paul Lynde was kind and helpful to Kearns. Stage legend Leonard Frey (birthday boy Harold from Boys in the Band) sat despondently during a sexy gay house party where looks trumped celebrity. The "monstrous" Charles Nelson Reilly was so threatened by Kearns' sexual identity that he cut short their visit in Florida to work on a project, throwing Kearns out of the guest house and squawking insults from the porch in his orange caftan as Kearns was driven away.

And then Kearns' story includes a bizarre intersection between us that I found so revelatory and disturbing that I had to actually put the book down for several days while I reexamined an entire section of my life.

During the 1980s I owned a gay phone sex company, Telerotic. It predated party lines and the Internet; customers called our office and "ordered" the type of man they wished to speak with, and one of my employees (struggling actors, every one) would call back the customer and take on the persona of whatever the client had ordered. I had opened the company after working for a competitor and discovering I was a very popular choice among the clients and had, well, a way with words.

One day, playwright James Carroll Pickett contacted me. He wanted to interview me, observe me doing calls with clients and get a feel for the business as research for a play he was writing. We spent a few evenings together as I answered questions, smoked cigarettes, made funny faces while talking to clients and snorted copious amounts of cocaine in my bathroom.

Months later I attended a performance of Dream Man, which would become the most heralded collaboration between the playwright and his theatrical partner, who performed the role of the phone sex caller in the searing one-man show.

The actor was Michael Kearns.

Watching the performance nearly 30 years ago was a surreal experience, but it was the playwright's inclusion of the mechanics of my nightly calls that were so striking to me: the rolodex box filled with client notes, the gimmicks I used to appear more engaged than I actually was, my tricks to get the client to call again by teasing him with an upcoming sexual adventure I wanted to be sure to share with him.

And I missed the point entirely. It wasn't until I read Kearns' book that the facts of the character he portrayed came into view: This was an isolated, frenzied and increasingly unhinged gay man with no prospects or esteem, playing to an audience of one -- whatever desolate client he could hold hostage during their phone call.

The play was an aria of anguish, but all I could focus on during that performance so many years ago was the damn rolodex cards. I was incapable of facing the "dark density" of the character, because if I scratched its surface, I would have clearly identified the drug-addicted, desperate young man whom the playwright had come to interview. And I may have revealed far more to him than I ever imagined.

Dream Man would be performed across the country, in Spain, Ireland, Germany. And through those years I continued my destructive path, having lost an opportunity for my own moment of clarity in the dim light of that West Hollywood playhouse. Reading about it now, in this book, rattled me to the core, and the book sat untouched on my nightstand for several days.

The last third of the book focuses on Kearns' adoption of a baby girl born to a crack-addicted mother, his selfless love for her, and how their bond throughout her upbringing conjures up everything from his fears of AIDS mortality to his unresolved issues with his own troubled parents. These pages are filled with a grace and maturity that are miles away from the drug- and celebrity-induced selfishness of his life thus far, as Kearns gently guides the reader down to Earth, into the bosom of family, after pages and years of breathless shenanigans.

"Acceptance is the answer to all my problems today" is a common refrain among those, like Kearns, dealing with recovery from drug and alcohol addiction. His book is imbued with that acceptance, just as reading it allowed me to accept whatever part of me was on display in the lonely, reckless stage creation Kearns most famously brought to shattering existence.