The other day I was visiting a family and their just-born baby in the hospital, and in the few short hours I was there, I heard a bunch of surprising comments:

- A nurse told a new dad (who was standing up, holding his 20-hour-old baby) to put the baby down in the bassinet, warning him that his son was safer in the bassinet -- otherwise Dad might drop the baby.

- A different nurse told a new mom (who was holding her 8-hour-old baby) that her daughter would be safer in the bassinet because Mom might doze off and "co-sleeping is not allowed."

Probably the first nurse meant: "If you did drop him, we'd end up with a law suit," i.e., it's potentially dangerous to us, the hospital, not: "It's actually likely you'll drop him." It's likely the second nurse meant, "I have been trained to warn mothers not to fall asleep with their babies in bed because for non-breastfeeding babies there are certain risk factors to bed-sharing, and I see so many new moms per day that I can't be more specific on an individual level," and not: "It's actually dangerous to for you to hold her right now, in bed, with visitors in your room."

Happily, both families took the comments with a grain of salt. The mom paused, concerned for a moment, but then looked around the room for encouragement and said, calmly, "Well I'm awake right now." The dad made a comment under his breath about Americans' fear of liability. Both families have older children at home.

But I worry about first-time parents who have no other experience and those who don't have visitors to help them remember common sense. Or who are just so tired and impressionable that they can believe that their urge to hold a newborn is wrong; that he's safer in a plastic box.

It's not that I think one statement in isolation is so damaging, but rather, the tide of small comments like this, pervading the new parents' experience in the hospital. Because while I was there, I also heard:

1. From a pediatric resident re: a well baby: "We're taking the baby's temperature to make sure she doesn't have a fever" (which suggests that she might have a fever, or might develop one),

instead of:

"We're doing our well-check up of the baby's vitals so we have a record of how healthy she is.")

AND

2. From a nurse: "Here's the breast pump. If you don't get enough to put in a bottle, we can give it by syringe" (which suggests that mom might not make enough milk -- a common fear),

instead of:

"One-day-old babies can only handle a tiny volume of colostrum because their stomachs are so small, and there's no bottle small enough to appropriately feed a baby this young, so, we'll give you a syringe you can put in her mouth, to give her the precious colostrum you get.")

(Or even better: "I hear you asked for a breast pump, so we're sending one over along with an IBCLC who can teach and advise you and help you figure out your options.")

AND

3. From an OB, to parents being discharged early after a healthy birth (unprompted, without previous discussion of infant feeding): "Definitely take home some of the formula. You can top him off after each feeding to make sure he doesn't get dehydrated" (which suggests that the baby will get dehydrated if "only" breastfed),

instead of:

"I'm not an expert on lactation, but if you have concerns about breastfeeding, let me get someone who can help you."

See how insidious this is? Each remark alone might be a smallie (the last one is not a smallie), but the cumulative message, over and over is:

Things are about to go wrong. You can't trust yourself or your judgment. That feeling of relief that the baby is healthy and in your arms? It's probably just wishful thinking and the rug is about to get yanked out from beneath you.

Newborn parents, who, for the moment, are tired, sometimes overwhelmed, understandably confused and facing lots of new stuff, are more vulnerable to suggestion than the rest of us. They need encouragement and support so that they can:

- Learn to take care of themselves and their babies;

- Learn to distinguish "emergency, requiring medical care" from "common sense situation I can handle myself;" and

- Learn to cope with the normal new-parent anxiety.

They deserve to encounter staff who understand their concerns, worries and knowledge level. They deserve staff who don't plant seeds of self-doubt and a culture of fear. We patients pay huge sums of money to be cared for while we are vulnerable -- it shouldn't be "caveat emptor": let the patient beware -- any advice you get may be misguided.

So, but here's the thing: I don't think that hospital staff who say stuff like this mean any harm. I don't think they intend to undermine parents' confidence or give faulty guidance. At all. I do think they may be influenced by the pressure to think about liability avoidance, and they may be too overworked to individualize service and attend to each new family's particular needs. Any of us can say the wrong thing when we're under stress because we're human.

But it should be a priority for all who work with pregnant folks and new parents to try to get that tone right as often as possible. To slow down, remember that that new dad holding his baby is far more likely to be riddled with insecurity and self-doubt than he is to actually drop the baby. It's so unfair to saddle him with the hospital's fear of a lawsuit when what he needs is to be reassured that he is competent and has good instincts. When we talk to him as though he already knows he's competent, we are not reaching our audience.

By the way, you know who does understand how to reach their audience? You know who never gets so tired or busy with their other priorities that they get off-message? You know who's really good at sending the message they mean to send?

Advertisers.

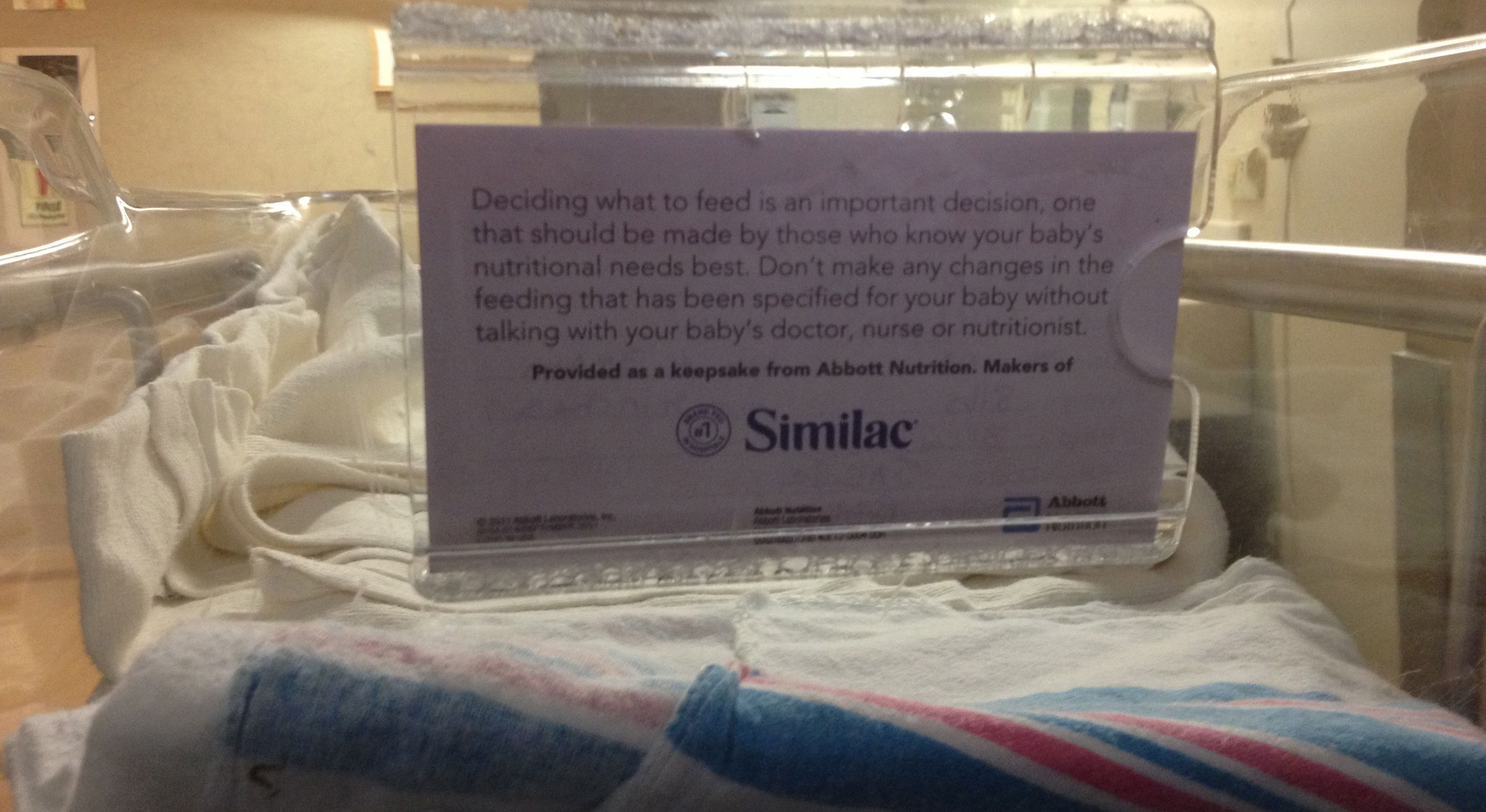

Advertisers think, all the time, about how their message will be received. That's what they're paid to do. And that's why, when I see a sign like this in every single baby's bassinet in the hospital, with the Similac logo and a completely horse-shit ambiguous message about infant feeding, I become pretty annoyed. I have two Ivy League degrees, decent comprehension of English and even got a full night's sleep last night, but reading this message, I feel completely confused.

That's because the message is meant to confuse me. I am meant to conclude that infant feeding decisions are very important and confusing and require complex micro-analysis that a normal person with normal breasts and a normal brain can't do, which is why, thank god, there are doctors, nurses, nutritionists (note absence of IBCLC in this list) and, most of all, Similac, bringing me this lovely "keepsake," a reminder that I am completely incompetent.

Note also that this solemn, authoritative missive about infant nutrition doesn't mention breastfeeding.

See how savvy this bit of marketing is? Similac donates these advertising cards to the hospital. The flip side of the card, which faces into the bassinet, says the baby's name, age and birth weight; the hospital accepts the cards so they don't have to pay to make and print thousands of name cards. The side with the Similac message faces out through the plastic and is positioned at eye level -- it's the first thing you see every time you look at the bassinet to check on your baby.

(Wait, why is your baby in the bassinet? Oh, because you've been told over and over to put him there).

Unlike hospital staff who are, I think, unintentional when they undermine parents' confidence, advertisers are cleverly exploiting parents' fears. This marketing message is aimed -- visually -- right at parents who are already a little confused, tired, worried that they don't understand everything. The message is this: You can't understand this stuff.

It's marketing designed to reinforce your worry and then sell you something to ease it.

Now look, we are lucky, in this time and place, to have ways to care for our babies if things do go wrong. But we shouldn't be starting there. Scare tactics and undermining messages should not be a part of routine patient care, whether by advertisers who do it on purpose or by well-meaning but careless, staff persons who do it because they're not paid to prioritize anything else.

We can do better than this.

WHAT YOU CAN DO IF YOU'RE AN EXPECTANT PARENT:

- New moms should not be isolated for long stretches. Have someone who knows and loves you with you, not only during labor, but to stay with you while you're in the hospital postnatally, to hold the baby while you nap, tell you how awesome you are and to help you make sense of everything else that happens.

- If you're feeling confused by what anyone has said, ask them to explain why they're recommending whatever they're recommending.

- If someone is saying or doing something that makes you feel nervous or anxious, ask for more information. Explanations demystify a lot.

- If you're told something that sounds like it doesn't make sense, entertain the possibility that you're right and ask for more information until it does make sense.

- If you have a clinical question about breastfeeding, it should be directed to an IBCLC. If someone is giving you breastfeeding advice, ask them what training they have had. Anyone can call herself a "lactation consultant." Is this person an IBCLC or not?

- Take the damn card out of the bassinet and throw it away. Put in a new piece of paper with your baby's age and name and weight. Or turn the bassinet so the card faces away from you. If you're feeling energetic, tell someone at the hospital that you don't like the Similac logo in your face. (After you get home, when you have the energy -- and this could be months later -- write to the hospital and/or your caregiver and let them know what you liked and what you didn't like. You can use these form letters as a model. Things change when people complain.

- If you're feeling like everything is desperately hard, it is a good sign that you need help, not that you're a failure already. Ring the nurse. Ask for help, and if it's not something she can help with, ask who can. Ask for help finding local resources for new parents in your neighborhood.

(You can read more "What Not To Say" posts here (grandma edition), here (why comebacks are hard) and here (general dumb remarks)).

This post was originally published on the author's blog, www.amotherisborn.com