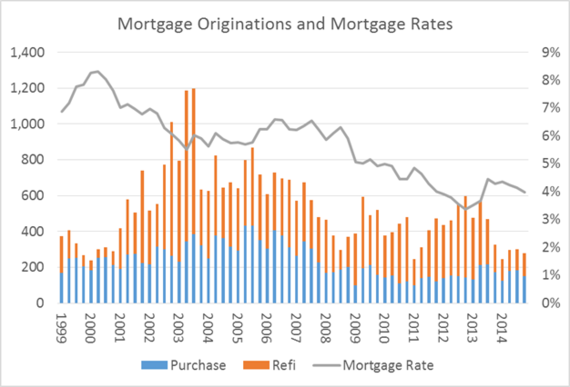

In the summer of 2013, a sharp spike higher in interest rates caused by the "taper tantrum" (fear that the Fed will soon end monetary easing) reduced both housing affordability and the opportunities to lower mortgage rates through refinancing. The result was a sharp reduction in mortgage originations during 2014. However, interest rates trended down throughout 2014 and into early 2015. In fact, in January of this year, the yield on the 10-year Treasury note (the common benchmark for mortgage rates), dropped to about 1.64%. The rapid drop in interest rates in January breathed new life into the struggling business of mortgage lending. The average rate for a conforming 30-year mortgage dropped to about 3.6% in January - not too far above the cycle lows of late 2012. As a result of the drop in mortgage rates, community and regional banks heavily dependent on mortgage operations will see a strong, positive bump in mortgage-related income for the first quarter of 2015. The bank with dominant share of the origination market, Wells Fargo, stands to benefit the most.

Sources: Mortgage Bankers Association and Freddie Mac. For interest rate data, we used the average of the weekly reported rates for each quarter.

Thus far in February, however, longer-term interest rates have begun to back up quite a bit. The increase is due to a number of factors, but the most important among them are stronger economic data (we would argue that the data are mixed) and the anticipation of a Fed rate hike by late in the year. Whatever the cause, the yield on the 10-year Treasury note, currently at 2.12%, is up 50 basis points from the January low. As usual, mortgage rates are following suit, and it's no longer possible to get a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage for under 4% (at least for now). If mortgage rates continue to climb, we can expect that the spike in mortgage originations in January will turn out to be just a transitory blip. For its part, the Mortgage Bankers Association sees mortgage rates rising to 5.0% by mid-2016, creating a huge headwind for both purchase and refi volume (in our opinion). For reference, a 5.0% mortgage rate would imply a 10-year Treasury yield of over 3.0% compared to the 2.12% today.

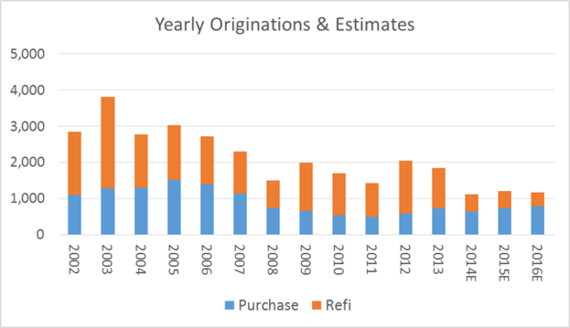

Source: Mortgage Bankers Association.

What is interesting about all this is the performance of bank stocks so far this year. In January, the KBW Bank Index, which consists of 24 large money-center and regional banks, fell 10% as mortgage rates tumbled and mortgage production spiked. In our view, the drop was somewhat overdue following strong performance over the past few years. But as interest rates rebounded in February, the bank index has regained nearly all of that ground and now sits only 2% below year-end 2014 levels. Again, we think the initial impulse to reduce exposure in January was the correct one. Why? Because we think the near- to intermediate term earnings outlook is not very good. In the face of massive regulatory pressures, contracting net-interest margins and weak loan demand over the past few years, banks have been sustained by two reliable sources of income: 1) the income associated with mortgage originations, and 2) the income associated with credit-loss reserve releases. As interest rates increase and credit losses trough, it will be very difficult to replace these sources of income. The market does not agree.

I understand the counterargument. The consensus expectation is that higher interest rates will lead to net-interest margin expansion for the banks. All those low-cost deposits that have been sitting at the Fed can now be invested in higher yielding assets, generating higher levels of net interest income. The investing public also believes that an improving economic backdrop will bring an increase in loan demand, which will provide further opportunities for growth in net interest income. The combination of higher net interest margins and better loan growth will more than offset the loss of both mortgage-related income and reserve releases. So goes the narrative, anyway.

Here's the rub though (and there are several). Economics 101 taught that as the price of something increases, the demand will decrease. In this case, investors expect that an increase in the price of money (ie, higher interest rates) will result in greater demand for money (ie, higher loan originations). I don't think that we can necessarily assume that that will be the case, at least not to any large extent. Moreover, the consensus believes that a big increase in purchase originations (ie, loans to buy a home, not refinance) will mostly offset a sharp decrease in mortgage refinancings. Here again, though, I don't understand the logic. From where I sit, mortgage rates set the level for housing prices. The rebound in housing prices from the financial-crisis lows was due to one factor: the availability of cheap mortgages. The Fed lowered the interest rates, and the federal government guaranteed the loans through Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae and FHA. It's as simple as that.

There is one final point. Banks are put at a significant disadvantage relative to, say, Canadian banks, because US mortgage borrowers are allowed to prepay their mortgages without penalty. This creates a huge challenge for banks in today's environment of low rates. There is simply no way to "match fund" the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage loans that banks underwrite. If banks originate loans and keep them on their own books (rather than selling to Freddie or Fannie) they must assume risk in three different forms: credit risk, interest-rate risk, and prepayment risk. This is why banks have been selling all their originations to Freddie and Fannie (or utilizing FHA insurance). At today's low rates, banks are not getting compensated for all the risks associated with owning mortgage loans. How the FHFA (the agency charged with oversight of Freddie and Fannie) expects to extricate itself from its primary role in the mortgage markets is a mystery to me.

Be wary of bank stocks. The gravy train is pulling into the station. While we maintain some exposure to the sector, we are underweight and invested in only the highest-quality names.