A very timely article in the Wall Street Journal covers a topic we have addressed frequently over the past several years -- the squeeze of the middle class. The article, entitled "Basic Costs Squeeze Families," by Ryan Knutson and Theo Francis, discusses the double-whammy of stagnating incomes and rising costs for necessities that is confronting middle-class Americans. While this long-standing trend should come as no surprise to anyone, the article does offer some new data that may be a bit surprising. In light of the lackluster retail sales over the all-important Thanksgiving weekend, we thought we would take this opportunity to revisit the middle-class dilemma.

The authors studied Labor Department data on incomes and spending for "the middle 60% of the population by income - households earning between about $18,000 and $95,000 a year, before taxes." This was a quick and dirty way to capture the "middle class." The period studied was the six years from 2007 through 2013, or from the beginning of the "Great Recession" until the last year for which we have data. We suspect that adding 2014 data over the next few months will not change the results all that dramatically.

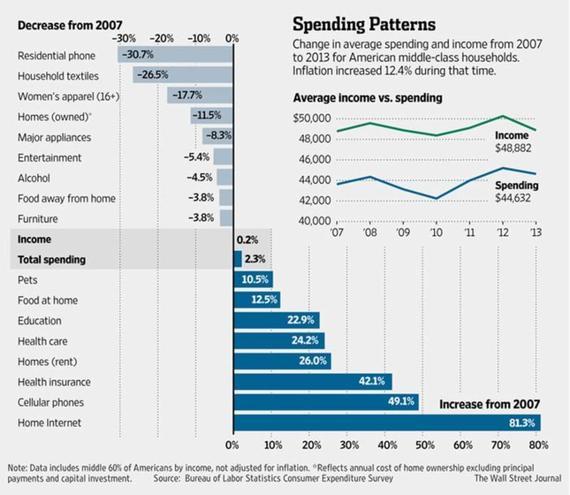

The first thing to note about the analysis is that "overall spending for the group rose by about 2.3%...even as inflation totaled about 12%. At the same time, income for the group stagnated, rising less than half a percent." I found it surprising that spending outpaced income for the group during a time when the savings rate increased materially. But remember, the authors are only studying a segment of the population. Wealthy Americans, for whom incomes and spending have grown at a much faster pace, were not included in the analysis. Secondly, and perhaps even more surprising, is that spending by the group did not even keep up with inflation! How can economists say the recovery has firmly taken root when spending by this huge segment of the population is not even growing with inflation?

On the expense side of the ledger, it is easy to see that middle-class consumers have had little room for discretion. Health care spending rose 24.2%, housing expenses (rent) grew 26.0%, education expenses rose 22.9%, and "food at home" rose 12.5%. Perhaps more surprising, the article breaks out expenditures for both cellular phones, which grew 49.1% over the period studied, and home internet, which grew a whopping 81.3%! While cell phones and home internet cannot be deemed necessities in the truest sense of the word, they do represent things that consumers are highly dependent upon and therefore are not likely to give up easily. At the same time, expenses that can be deemed truly discretionary, like clothing, furniture and entertainment, have suffered dramatic declines. In other words, middle class Americans had to tighten the purse strings not only during the recession, but for the full duration of the recovery thus far!

We have argued repeatedly that the Fed must recognize that the vast majority of middle-class Americans are not benefiting much from the economic recovery. The median household income in 2013 was only slightly above that reported for 1995 (after adjusting for inflation), while costs for necessities like housing (rent), health care, and education are making it much more difficult for middle-class folks to get by. We have said that the Fed's traditional gauges of inflation are flawed because they do not consider the fact that costs for basic necessities have risen at a much faster rate than the cost of more discretionary goods and services. And finally, we believe that the surge in asset prices (stocks, bonds, housing) represents a very real source of inflation for those of us who would like to retire some day. The rationale is that investing at much higher valuations today will result in lower expected returns in the future. Given the fact that the vast majority of us have not saved enough for retirement, lower expected returns will create an additional financial burden.

We think the Fed's lengthy Quantitative Easing program was misguided and short-sited. The resulting financial dislocations and distortions are likely to be felt long into the future. If I were to articulate one message to Janet Yellen it would be that higher stock prices are not an unambiguous positive. Surging stock prices do represent a very real cost (and source of "inflation") as they raise the cost of saving for retirement. Perhaps the Fed has finally gotten the message, but it may be too late.

The Squeeze of the Middle Class

The median household income in 2013 was only slightly above that reported for 1995 (after adjusting for inflation), while costs for necessities like housing (rent), health care, and education are making it much more difficult for middle-class folks to get by.

This post was published on the now-closed HuffPost Contributor platform. Contributors control their own work and posted freely to our site. If you need to flag this entry as abusive, send us an email.