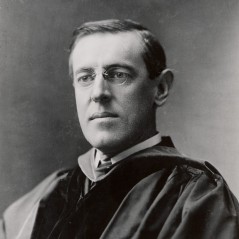

As a graduate of Princeton University's Politics' department (Ph.D. Politics, 1991) and one of only two black Ph.D candidates in my graduate student cohort, I have followed recent student protest around the legacy of Woodrow Wilson at Princeton with great interest. As anyone familiar with Princeton's campus knows, Corwin Hall, the building that houses the Politics department, stands adjacent to the Woodrow Wilson school of Public and International Affairs, its entrance facing south.

Much of the emphasis on Woodrow Wilson's legacy at the university has focused on his commitment to racial segregation at the university and in the federal government during his respective tenures as the 13th university president and 28th president of the United States. As several biographers of Wilson have noted, Wilson's antipathy toward blacks in the United States is amply documented. As the chief executive of a major research institution and president of the United States, Wilson was an architect and agent of segregation. He created or maintained policies of racial segregation and inequality. Wilson was the last Ivy League president to maintain a policy of Jim Crow exclusion of both students and faculty. Soon after entering the Oval Office, he resegregated the Federal government, firing many black federal employees, focusing especially on those who interacted directly with white federal employees.

Several journalists, along with student protesters at Princeton, have juxtaposed Wilson's racist perspectives and policies of the early 20th century, with present-day commitments to creating an environment in which black and brown faculty, women, and students can thrive. Certainly the current crop of black and brown students matriculating at Princeton would have been prohibited from attending the institution during Wilson's tenure as university president. But then again, they would not have been able to attend most colleges and universities (nor elementary, middle and high schools for that matter) where whites matriculated. Perhaps this might be one way of gauging progress made across the country over the latter half of the 20th century in particular, on racial desegregation.

Most criticism of Wilson's record, however, only focuses on the domestic side of Wilson's racist vision, when in fact, the 28th president's segregationist policies were part of a larger global vision of Aryan supremacy (that's right, Wilson used this term) in which Aryans, as state makers par excellence, were destined to rule over the darker and less capable races of the world. Wilson's vision of Aryan political supremacy was nurtured during his years at Johns Hopkins, and found its way into what many scholars consider Wilson's crowning achievement -- and biggest failure -- the blueprint for the League of Nations.

Wilson, completed his doctorate in history at Hopkins between 1883 and 1886, and participated in the Seminary of Historical and Political Science, founded by Herbert Baxter Adams, a prominent historian of U.S. history in the late 19th and early 20th century. Adams was also one of the founding members of the history department at Hopkins, the first research university in the United States. Adams believed in Teutonic supremacy, particularly in the realm of politics, along with an evolutionary approach to understanding history and political development. There is enough primary evidence in Wilson's scholarship, journalism and letters to suggest that his outlook on the question of nationality, race and state was deeply influenced by the scholarship of Adams as well as Edward Augustus Freeman, Thomas Carlyle, and other adherents to the Teutonic or Euro-Aryan view of world politics and global supremacy.

The first piece of evidence of Wilson's views on the relationship between race and democracy can be found in an unpublished manuscript on modern democracy entitled The Modern Democratic State, which the editors of his papers surmise is an earlier draft and foundation for his later work, The State. It is in this text were Wilson outlines pre-conditions for democracy in modern nation-states, and proclaims the following as a first-order priority;

homogeneity of race and community of thought and purpose among the people. There is no amalgam of democracy which can harmoniously unite races of diverse habits and instincts or unequal acquirements in thought and action... A nation once come into maturity and habituated to self-government may absorb alien elements, as our own nation has done and is still doing... Homogeneity is the first requisite for a nation that would be democratic.

Like many nationalists and racialists of his era (not just advocates of Teutonism and Euro-Aryans), Wilson stood by the erroneous assumption that most modern-states had homogeneous populations, and that diversity and democracy did not mix. Not only is this belief empirically false, since the overwhelming majority of nation-states throughout the world -- including European ones -- started out with highly diverse populations (whether based on religion, ethnicity, language or presumed race). The race construct provided the means for Wilson and kindred thinkers to proclaim that German, Italian, Polish, Scottish, Irish, Spanish and other nationalities who made their way into the United States were somehow homogeneous, when in fact they were a diverse array of peoples with different languages, norms and origins.

Wilson's book, The State, his best known work of scholarship, provides an unambiguous statement of his racist world-view as both statesman and scholar, providing insights into a method of study which he considered most fruitful for students interested in understanding political development in Europe and the United States:

In order to trace the lineage of the European and American governments which have constituted the order of social life for those stronger and nobler races which have made the most notable progress in civilization, it is essential to know the political history of the Greeks, the Latins, the Teutons, and the Celts principally, if not only, and the original political habits and ideas of the Aryan and Semitic races alone.

Wilson did not believe that African, Arab and Asian peoples were capable of self-governance. In this sense, his vision of internationalism remained consistent with his perspective on the prospect of Negro or Native American self-governance in the United States, two groups among a larger category of peoples literally unable, in his view, to determine themselves politically. At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Wilson and several of his cabinet members, helped scuttle an amendment proposed by the Japanese delegation to the conference to include a clause on racial equality for the black and brown races.These and other acts demonstrate Wilson's influence on domestic, foreign and international policy at the end of World War I, thereby situating his vision upon a global theatre.

What relevance does all of this have for Wilson's legacy and for contemporary students of any color at an institution such as Princeton? Campus debate about Woodrow Wilson's contributions to Princeton, and to domestic and global politics could serve as an important teaching moment for a larger public -- not just Ivy League students -- to reveal a prominent historical figure as a human being with very human flaws or at minimum, with ideological positions that are no longer consonant with enlightened contemporary public opinion.

To be sure, there are supporters of Wilson's views in the present moment who will strenuously uphold Wilson's perceived achievements in domestic and world politics along with Wilson's ideological positions; opponents will simply dismiss him as a rabid racist, nothing more. President Eisgruber's open letter to the Princeton University community is a thoughtful first step, in my opinion, for opening dialogue about Wilson's prejudices and actions as head of the University and head of state. These discussions could provide an opportunity for students, faculty and a broader community to also consider the legacy of white supremacist thinking in U.S. foreign policy during and after Woodrow Wilson's presidency, up to, arguably, the Vietnam War, in which a belief in a world racial hierarchy, along with Cold War and imperialist logics, informed U.S. politics at the highest level of government decision-making. The U.S. government's involvement in present day military deployments in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria in the "war against terror", coupled with the tendency for the Western press to depict ISIL's attacks in France, the U.S., and Belgium as evidence of a "clash of civilizations" or "civilization envy" by ISIL converts, bears traces of an old Cold War logic combined with a very Wilsonian view that some "races" (now cultures or religions) are better equipped for modern state-making and civilization than others.

While on sabbatical last year, I attended several student demonstrations on Princeton's campus, and in the town itself, in response to the spate of police shootings of black and brown youth across the country. These demonstrations can be viewed as local manifestations of the "Black Lives Matter" movement that came to prominence after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, which incidentally, is the town that produced several football players currently on the University of Missouri football team, the same team that threatened to boycott its competitive schedule if the university president was not replaced. These and other student demonstrations evince the manner in which "local" student protests actually link the daily terror experienced in many black and brown communities ( which includes police and community generated violence) to a larger" war on terror" in foreign and increasingly, domestic policy . As noted by Sean Wilentz in a New York Times Sunday Magazine article written soon after the Oklahoma bombing in 1995, the United States has a long history of so-called home grown terrorism, namely white supremacist organizations inflicting violence upon civil rights activists and organizations, but also "innocent" people -- black, Jewish, white and Christian -- in their quest for racial homogeneity.

Current student protest against "home grown terrorism" (recounted in the film Selma which depicts the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963) also has its precursors in previous generations of black student protest, at least since the 1930s, in which students linked U.S. domestic and foreign policy. The double V campaign during World War II was organized by students of the National Negro Congress (1936) and the Southern Negro Youth Congress (1937), linking the Allied fight against the Axis powers to the fight against Jim Crow and racial terror in the United States.

This current wave of student protest around the historical legacies of their colleges and universities has an additional international component worth examining. In March of this year, college students at the University of Cape Town, South Africa (UCT) participated in the Rhodes Must Fall campaign to rid their campus of monuments and landmarks glorifying apartheid and colonial leaders, Cecil Rhodes among them. The collective statement of students, workers and staff at UCT contains demands that are quite similar to current black student protesters in the United States; changes in curricula, an increase in the number of faculty of color and administrators, along with an overhaul of the institutions material iconography. The legacies of slavery, colonialism, empire and white supremacy frame student demands in both contexts.

How different are such protests from the tearing down of statues of Stalin and Lenin in the countries of the former Soviet Union, of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, or the Berlin Wall? Compared to the protests in these and other parts of the world, the occasional defacements of monuments to leaders of the Confederacy in South Carolina and Baltimore, and to plaques and statues honoring proponents of slavery at Yale, Brown and now Princeton are tame. What these examples in different parts of the world share is the desire of people to have national symbols that reflect their society's best, collective aspirations.

In a country as large and plural as the United States, rarely does a monument, especially a national monument, garner unanimous approval and praise. Consider the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C. But I would suggest that one sign of deepening democratization of a national political culture is the capacity of its citizens to imagine -- and act upon -- changes and revisions of its national or local symbols to reflect the expansion of the franchise to formerly excluded groups (whether former slaves or immigrants), as well as the diminution of symbols that lauded historical actors whose beliefs and practices served to enrich and ennoble a dominant population at the expense of the excluded, weak and less fortunate. Thus, in my view, the lowering of the Confederate flag in front of the state building in South Carolina is as symbolically important as the Allied demolishment of the swastika perched atop the Zeppelinfeld at Nuremberg in April, 1945.

Monuments, as symbols, project values, not neutral representations of the past. One of the momentous changes brought about in part by the civil rights movement in the U.S. is its role in helping shift national norms and ideals about who should and should not, participate in the polity, in the relationship between government and the governed, who can make legal claims, and who cannot. It's called egalitarianism, which is supposedly one of the virtues/assumptions of U.S. political culture, with authoritarianism, slavery, empire, colonialism and gendered chauvinism as its opposite. Based on this belief in the power of democratic social movements to transform values in a national society, I support efforts, whenever possible, to rename or remove monuments that directly or indirectly extol the deeds and character of historical figures most associated with genocide and the comprehensive marginalization of minority populations.

Obviously, there are instances where complete revision or removal is an impossibility. In those instances, it might be more practical to provide alternative monuments to an historical figure or incident, alongside or near the historical representation in question. Examples of such a practice include the tours and reenactments of the Alamo on San Antonio, Texas, by Chicano community activists, or the recent and unfortunately temporary installation honoring a black freedperson's settlement and burial ground in Brooklyn, NY, as well as a monument honoring the site of the Stonewall Rebellion in New York City, or the efforts to remove Andrew Jackson from the $20 dollar bill. As for university buildings, which often cannot and should not be razed, renaming is a good option.

At public and private academic institutions across the country, buildings are routinely renamed to honor wealthy donors whose gifts exceed contributions made by the donor whose name previously graced a building's façade. If buildings can be renamed because of money, shouldn't we consider the possibility of renaming buildings and other sites on ethico-historical grounds? Thus, the current controversy over the naming of a building and its renowned school of public affairs is at once unique to Princeton and at the same time symptomatic of a larger challenge for educational institutions in the United States. U.S. educational institutions not only help train future generations of U.S. citizens but increasingly, people from all over the world, whether in an old fashioned classroom or via virtual matriculation.

I have one cautionary word of advice, however, for those protesting students who seek to have more faculty and teachers who "look like them"; while the number of faculty of color at many institutions is paltry (Johns Hopkins, my current institution currently only has four black faculty out of a total of 300 at the Kreiger School of Arts and Sciences, an embarrassing statistic), do not correlate the color of a professor's skin with their capacity to provide you with a first-rate education. There is a wonderful and inspiring history of Jewish educators fleeing the Nazi onslaught across Europe in the 1930s and 1940s who taught at historically black colleges and trained several generations of students who would become leaders in the civil rights movement, industry, sport, arts and entertainment.

In a society with a general lack of historical awareness, and government has never formally apologized for the institution of slavery or the profits generated from it, any discussion about the degree to which institutions of higher learning were complicit with slavery and apartheid is bound to be difficult. Frank discussion about such monuments -- tributes to a grim past -- are necessary first steps in enabling further discussion about the overall climate for students of color, administrators and faculty at colleges and universities throughout the country. If students represent the future, then the relative absence of students of color at liberal arts colleges, major research universities, and in postgraduate education altogether, projects a pessimistic message about the likelihood that the current generation of undergraduates will eventually replace the current crop of faculty of color at major research institutions and liberal arts colleges. The current generation of college students -- and not just the protesters -- deserve better.