Last week I had a long and fun Skype talk with Dan Shapiro. Dan and I met at the last Maker Faire in New York and we really hit it off. Dan is an entrepreneur, inventor, designer, software designer and all around interesting guy. I wrote a little about Dan's new venture Glowforge here a few weeks ago. Below is an excerpt of our conversation. Enjoy.

MLN: So how are you doing, man? Congratulations on the Kickstarter campaign!

DS: Holy crap, thank you. I had no idea what we were stepping into last time we connected. It's been wild, absolutely wild. We had our "holy crap, I hope we get this far," we have our bottom number, then we had "in our wildest dreams, maybe we'd hit it" number, and then we had what we actually did which was like, five times that. [laughs]

MLN: Okay. So, let's start off. Just tell me briefly who you are and what it is that you do..

DS: So I went to school for engineering and put myself through school with a DJ business, which came about because my friend and I built laser shows in our dorm room and then people said you should bring those to a party, and then people said "while you're here, you should play some music." So I wound up with a DJ business. I had to work at a big company, Microsoft, for five years, and toiled in the salt mines at the software industry and worked on like, Windows 98 and Windows XP - you know the ones that didn't suck too badly. [laughs]

I co-founded a company, it was originally called Ontela; It's now called Photobucket. It's still cranking along. After four years, I left and started a company called Sparkbuy, which I sold to Google. I spent two years at Google and then invented the board game with my kids and thought, "Oh, I'll put this on Kickstarter just for fun over the summer while I work on this book" and then that blew up and totally surprised me.

MLN: The Glowforge. How did that come about? Was this your idea or was this something other people had started and you joined in? I feel like you're the man behind it, I feel. Or at least it's perceived that way in the public.

DS: The origin story is that I had created this game Robot Turtles and it was blowing up like crazy and a bunch of people said, "Hey could you do something special?" Like, "Could you create some sort of memorable addition of this that's really beautiful and lasting?" And a friend of mine said, "Yeah, I want that and I want the Turtles to be something that my son can like, keep in his pocket and walk around with all day." And I thought, this is awesome! And for years I've been wanting to want a 3-D printer. I didn't actually want a 3-D printer, but I wanted to want one. They seem like such a great idea. And I was like, I just need to find an excuse to need one so I can justify buying one.

MLN: Yeah.

DS: So this seemed like a good excuse. Everything was printing ugly plastic slowly. And, so I looked and I'm like, "this isn't what I want to make these things out of." So a friend of mine who worked at Boeing took me on sort of a verbal tour of the machine shop and he described each of the machines and what they could do. And I was trying to find one that would make these beautiful parts and when he got to the laser, I said "Oh, wait a minute. The Turtles have lasers. How perfect would it be if there was, like, a laser edition?" And you know, I'm partial to lasers. I did that in school, so I ordered this ridiculous $11,000 industrial carbon dioxide cutting laser direct from China. It took months to arrive. During the government shutdown, it got stuck in the port because the inspectors wouldn't let it through and when it showed up, 770 lbs shipping weight, a forklift installed it into my garage - I have a very patient wife - she actually helped me move it in, un-box it, kind of vent it out the window. It was just utterly ludicrous.

MLN: [laughs]

DS: So I get it up, and I start to try to get it to work and it takes me days. And the process of configuring it involves things like, Step 1: disable all the safety interlocks. Step 2: you know, put on all the safety equipment and fire the beam into a piece of masking tape. Move the knob a little bit, put on a new piece of masking tape and burn a new hole in the masking tape and see if the hole is to the right or the left of the first hole. And I'm just staring in shocked amazement that this is so ridiculous and horrible and the software was even worse. So it took me a month to get this machine to do anything useful or interesting. And, finally I got a program to start making the parts for this deluxe version of the game.

MLN: So with this laser, it was just pretty much like this giant machine that shot a laser beam out that did just cutting, pretty much, right?

DS: Cutting and engraving, yep. So, it could draw on the material and it could cut out the material. But it was just so horrible, right? It was designed for somebody to spend, like I did, spend a month getting it to do one thing really well and then it would do I over and over again. And the part where it actually printed things was like magic, but everything else was just terrible. And so, I wound up calling a couple of friends who both were accomplished entrepreneurs and one of them was a designer. And I said, "What could you do with this?" And the other was an electrical and mechanical engineer, and I said "Could you make this not suck?" [laughs]

MLN: [laughs]

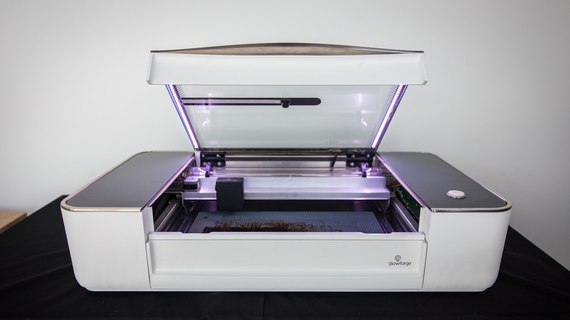

DS: And so we spent a summer talking to all the people who use lasers and talking about what it could do and how it could work and brainstorming all the technologies, modern technologies that we could bring to bear, because there was nothing - like, if took this ancient Chinese beast, recently made, fresh off the assembly line, but you could send it back in time to 1995 and the only thing would look weird was the USB ports on the back. Like, nothing about it was particularly advanced. And so we started saying, "What if we took all the sensors you have in an iPhone and put them in the laser? What would happen?" What if, instead of having this like, crappy little onboard computer, you had a super computer running in Google's cloud controlling it? What if the software was, beautiful, delightful-to-use instead of this comically absurd, brutally translated nonsense? And came up with the core of the idea for what was ultimately going to become Glowforge, which has many features and capabilities that that Chinese machine doesn't, but it's fundamentally very similar in its construction, which is that you put in a piece of raw material and then it uses this laser beam to carve and engrave that material to create the final product.

MLN: Does the laser beam last forever? What kind of maintenance is required on that?

DS: Yeah, the tube can last about two years. It depends on how often you use it. But the rated life is typically two years. And it's a glass tube. It actually bears resemblance to a neon sign in terms of how it's made. It's hand-blown by master glass blowers, believe it or not, and it's a technology that probably most commonly used in dermatologist's office, when they do the laser, this that, hair removal and that sort of thing, but it's a really old technology. It's been in industrial use since the 80s.

... it encodes data into the disc by modifying the disc with the laser light. It's funny, the laser in the Glowforge is a 40 or 45 watt laser, which means it puts out as much heat as a 40 or 45 watt light bulb, but it packs all that heat into a spot that's eight- one-thousands of an inch across, and so that one spot is very warm. But, people are always surprised when they take the material out of the laser, and they're like, "Oh, it's not going to burn me. It's barely warm." It's like, yeah, it's not that there's that much power, it's just packed down into this one tiny little spot and that's where the magic happens.

MLN: It's interesting to me that you were able to take something in its crude form - and so it's something like $11,000 when you bought the Chinese laser just to experiment - and you were able to crunch it down to something that does so much more at a fraction of the price. And I think that's the economic advantage. Much like the personal computer revolution. It was just the same idea, putting more microprocessors onto a chip. Can you speak on that a little bit?

DS: !t comes from those revelations in consumer electric products. So, one way to think about it is that a 3-D printer in a Glowforge and many other devices are called CNC machines. It stands for computer numerically controlled, which basically just means that they're a robot. And in the 3d printer, the robot has a little tiny hot glue guns. That's how a Makerbot works. And it squirts the plastic into shapes; it builds it up layer by layer. Instead of building up layers of plastic, it's carving away and it's removing material.

MLN: It's a diminishing project. You know, in sculpture, there's two ways to do something. You're either adding something or taking something away.

DS: Yes, exactly right. It's subtractive instead of additive, is the technical term. And so, when you think about it from that angle, there's two ways you can build a robot. One is, you go buy a bunch of motor units and processor units and connector units and put them all together and then you go buy robot software from somebody and that's how you go build a really inexpensive robot.

The other way is you go in and you buy really inexpensive motors and wires and you create your circuits from scratch and everything else, and then you go find a factory that can mass produce them. That costs a lot more up front to figure out the production process, but what comes out is a little cheaper and better because all the parts are exactly what you need and you're not paying a mark-up for each component. Most of the lasers on the market are built out of these components that are really designed for other things in many cases, and so they're buying parts from third parties and wiring them together and they're not quite perfect for the job and then you have to pay mark-up and you have to get them all working together. Whereas, basically everything in the Glowforge is designed for it and that gives us all sorts of advantages.

I'll give you just one really crude example, which is the Chinese laser and most lasers have somewhere on the order of five or six different air systems, like different fans, although each air system can have multiple fans that move air to do different things. So, there's one fan on the electronics to keep it cool, there's one fan that blows air out of the enclosure, there's one fan that blows air out into the cut line, etc. So, there's all this redundancy. Because we designed it from scratch, we were able to use a much smaller number of fans and less air flow to accomplish the same task or better, because we know that the electronics are where the air comes in the machines. So, the air goes over those and then it goes over the cooling fins for the tubing go out the rear. And so we're able to use lower cost, it's quieter, it uses less power, it's more efficient, it's smaller, and get better results.

MLN: Let's talk about "angel investing". You may remember in the article I wrote, that I said this was a revolution that was going to start on Etsy. And, I really believe that. I live in New York surrounded by art people, and many are hardly tech people. Sometimes they cross over. The Maker movement seems to embody both of them. However, I see this as something that people are going to be able to use as art in the way we use Photoshop now or the way we use something like that that has become a standard.

DS: I hope so.

MLN: The disruption of manufacturing is quite interesting to me in an economic sense. Was this something that was built into the Glowforge originally, or is this a byproduct of how the Glowforge turned out?

DS: The way it came about was when I was working with Tony and Mark, my co-founders, and a big part of what Tony and I were doing during that time was trying to figure out who uses lasers today and what they use them for. So, we went to maker spaces and we talked to the folks who were using the 3-D printers, we talked to the folks who were using the hand tools, we talked to the folks who were using the lasers, and the most interesting thing to me was the comparison between the lasers and the Makerbots. I'm saying Makerbots - the 3-D printers. The people that were using the 3-D printers, the most common title that they described their job as was "engineer." They were disproportionately male and the thing was, almost always as a proof of concept or a prototype, or a conceptual. Then you go to the lasers. The most common title was some variation on "designer," the average user was more likely to be female than male, and they were almost exclusively making things that were going to be used. They were going to sell them or they were going to gift them. And so the thing that almost stopped us from creating the company and the product, Glowforge, was we just weren't interested in building a less expensive laser. We were interested in finding something that was going to change the way the world works. We weren't quite sure what that was going to be.

MLN: How do you know?

DS: There's been a running series of thoughts about like, "Where's my jet pack?" And, "Why aren't any start-ups working on jet packs? Why are they working on apps?"

MLN: [laughs] Right.

DS: So, I said this early on to my co-founders. We are really lucky and privileged in so many ways. And if we use that fortune and privilege to go build an on-demand hailing system for, you know, banana vendors, then we don't deserve it. We should be doing something with our good fortune and with the privilege we have been granted that changes the world in some meaningful way. That take some significant risks that not just anybody could do. And so, the thing that was exciting to us was seeing - and it wasn't obvious at first, but when we looked at this technology that seemed to hold so much promise, that saw that this was not something that was being used as a gimmick or as a one-off, as a sort of "oh, look what technology could do." People who have better things to do with their time that fight with technology were fighting with the technology because it was so valuable, because it actually let them create things more quickly and more beautifully and with more flexibility than they'd ever been able to before. So, yeah, it was baked right into the essence that this is a way that we can change things for people and change things for the world, not just create a nifty consumer product that people would go buy each other for Christmas.

MLN: You know what really impressed me? The doll house. The doll house was like, I thought to myself, "Wow, this isn't just an abstraction. This is the real thing."

DS: My wife actually turned to me one day after the kids had just asked me to make a sheriff badge. And she said, "Have you noticed that the kids have asked us to create things for them more than they're asking us to buy things for them?"

MLN: That's fantastic.

DS: And it just hit my like a load of bricks. Like, this is something they're going to take for granted. Of course, if you want something that doesn't exist in your world, you just make it. Why would you? You know, of course. That's such a very kid-centric view of the world, but it's one that we suppress over the years.

MLN: So, let's go back a little bit. I want you to tell me with as much hate in your voice, why you loathe the term "angel investor"? [laughs]

DS: [laughs]

MLN: I love this kind of shit.

DS: So, I think that the biggest problem with investors is the pedestal that people put them on. The fact that somebody has accrued some excess dollars in their lifetime, the fact that they once invested in a startup says very little about the merit or worth of the person and their ideas. And so it frustrated me when I was pitching that I didn't understand who these people were, or what they wanted or what was special about them because the secret answer was, there wasn't anything really special and there were people and they all wanted different things. And, it's a hobby; it's not a statement of self-worth or existence to invest in startups. And that people who do that as a hobby are no different are no different from people who do other hobbies for the most part.

MLN: Wow. They sound like art collectors, you know? The modern-day Medicis. [laughs]

DS: [laughs] And some like to think of themselves that way. But as somebody who does that, I think you do, and it's the thing you do because you happen to have been blessed with the resources to do it, and because you happen to be excited about it. But everybody does it for their own reasons. And it's an incredibly important part of the ecosystem. There are so many great opportunities that the world has because a few wealthy individuals stepped out and made it possible. It's like the difference between fathering a child and parenting a child.

MLN: That's a good analogy.

DS: And I just thought of that. [laughs]

MLN: [laughs]

DS: Thank you. And the latter is so much more important and difficult than the former. So, I've done both or all four depending on how you think about it [laughs] and it's great to invest in a company, it's great to see what comes of it, but your role as an investor is always going to be a small one. And so, when people use these divine terms like "angel investor" and escalate that activity to a pedestal, I think it tends to glorify something that is really quite straightforward and transactional. And I am eternally fortunate that I have had the ability in my life to be able to go make those kinds of investments and contribute, but if a company that I'm a part of becomes a success, it's sure not going to be because of my contributions as an investor anymore than a tiny bit around the margins.

MLN: "Angel" reeks of religious piety. [laughs]

DS: [laughs]

MLN: I see that could be problematic.

DS: And that term, altruism. I think that's my other problem with the term. It reeks of altruism, and while there is sometimes an altruistic motive in "angel investing", there's an altruistic motive in lots of jobs and I don't think angels are any greater altruists than people who are passionate about what they do in many other fields, and there are far more noble callings than financial investing, as my friends who work in the non-profit world can attest to. And I think that bugs me a little bit, too. It's great that people are excited about investing in start-ups. It's great that they can make money while simultaneously helping other people create things in the world, and you know, some start-ups are good and some are bad, but on the whole, I think that creation is better than not. But, I think there's a little bit of a pedestal there that, I hate to say this, but, we "angels" have put ourselves on that isn't deserved and the world would be better without.

MLN: Yeah, that's a very humanistic view. I agree with you, I mean, why not? It just makes sense. You seem to have this tremendous energy towards your projects and towards your life. What is it that inspires you and keeps you going? That's kind of something that I ask a lot of creative people because it's something that's continuously fascinating to me. Some people feel quite happy with their lives, so they feel very alive, some people do a lot of drugs. I don't know what motivates people. It's kind of interesting, if you care to comment on how you roll.

DS: There's this thing that happens with people's stuff, whether it's this funny thing I saw on the Internet, or this idea I came up with, or very rarely, this project that I created, where their faces kind of light up where the go, "Oh! That's really amazing!" And I am a total addict for that. There's nothing I love more than showing people something that gets them excited. This is my favorite part of parenting because my kids are the easiest audience for this in the world, the ages that they're at. In fact, when I created Robot Turtles, part of it was that, I want to take that "Ah, ha!" moment and put it in a box that I can pull out whenever I need it, whenever I'm feeling short on inspiration and I can share with other people that they can pull out and get their "Ah, ha!" moment. I love that. And my whole career is about trying to bring more of that to the world. About taking beautiful, wonderful, delightful, amazing things whether they be software, hardware, projects or ideas, or whatever - and saying, "Look at this!" and having people go "Wow! That's really neat!" That's meaningful and impactful to my life in some way, so that's every startup, that's every activity, that's every weekend outing with my family, that's what gets me going.

transcribed with love by Courtney Eddington