Karima Bennoune is someone who collects nightmares for a living, a woman who makes people weep. With over 20 years of human rights research and activism in her professional experience -- including a period as legal advisor to Amnesty International -- Bennoune has collected stories that most of us would have trouble listening to. Living a sheltered western life makes it almost impossible to grasp the magnitude of human cruelty and suffering she has heard.

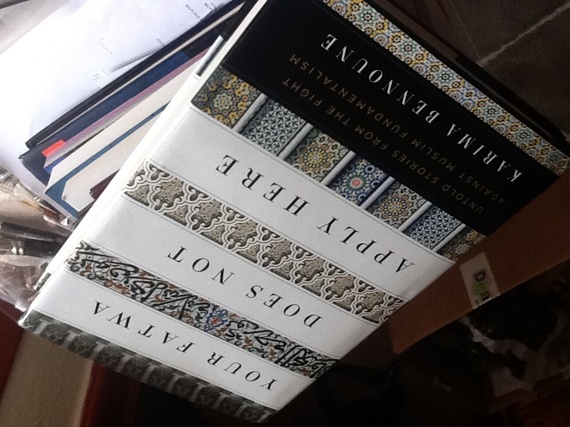

Your Fatwa Does Not Apply Here: Untold Stories from the Fight Against Muslim Fundamentalism is not as easy book to read, but not because of literary incompetence. On the contrary. Bennoune writes beautifully, organizing her material thematically in 12 chapters that makes the material immediately accessible. It's the subject matter itself that repels and haunts, while simultaneously challenging one's thinking about the relationship between Muslim fundamentalism and women's rights. Speaking recently on Capitol Hill at a screening of a documentary about a progressive form of Islam, Bennoune asserted that most Westerners do not appreciate the full extent of the Muslim fundamentalist war on women. The urgency of the issue is simply lost on most people, she said. Take Afghanistan, for example. Bennoune is in favor of military intervention and deeply concerned about America's illusive exit plan.

Her stories have impact. They'll force you to re-evaluate the opinions of fashionable western cultural relativists, who sometimes justify veiling and FGM as authentic and unassailable cultural practices. She wants us to see women's rights as human rights, and cultural relativists as misguided individuals simply purveying another kind of racism.

Bennoune's stories will awaken you to the clash within civilizations, not just between them. Most of all, her stories will make you re-evaluate whom you consider to be Muslim moderates, followed by the question: So what? Bennoune cuts Muslim moderates no slack, if they cannot recognize the human rights of women. She warns us about cooperating with so-called Muslim moderates just because they are not jihadists.

Thus, one of Bennoune's assertions is that the Left gets it wrong almost as often as the Right. She is vocal about her sense of betrayal on the part of the western liberal Left who, in their eagerness to denounce imperialism, military intervention and the drone abuses unleashed by the so-called war on terror, have ended up ignoring some fundamentalist, Islamist tendencies with little judgment about their policies or record. She offers as an example the pro bono representation of the interests of the late Anwar Awlaki and his family by the U.S. civil liberties group, the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR). They made no effort, she asserts, to recognize Awlaki's own record and his culpability in issuing threats of assassination. He is not called a terrorist, but simply "a Muslim cleric."

Algerian by birth, Bennoune is defiantly secular and a self proclaimed agnostic. Fluent in Arabic, French and English, she interviewed nearly 300 people for her book from almost 30 countries -- from Afghanistan to Mali. They include teachers in northern Mali who risked everything to maintain their co-educational schools under jihadist authority; women lawyers in Afghanistan who were brave enough to prosecute cases of violence against women despite Taliban threats; feminists in Egypt and Tunisia who went into the streets to participate in revolutions against totalitarians and then struggled to stop those revolutions being hijacked by Islamists.

Chapter 4 is devoted to journalists, the ones who literally risk their lives to bring the world information. One of the book's more macabre sections describes the realistic acceptance of their existential choices and how they imagine their deaths, hoping for a quick, painless bullet in the back of their heads, instead of a tortured death, such as the one experienced by their colleague, Wall Street Journal reporter, Danny Pearl when he was beheaded.

Bennoune writes, as an example, about the fearless reporting of journalist, Salima Tlemcani (not her real name) concerning the "horror in Bitouta" in 1994 when two sisters were abducted to become divinely sanctioned sex slaves. The leader of a fundamentalist armed group and his men had invaded the home of a poor family in order to take the two daughters, aged 15 and 21, for what was called zaouedj el moutaa, or temporary marriage. When the girls' family tried to intervene, the men literally dragged them away by their hair. A few hours later their decapitated and mutilated bodies were found on a nearby expressway. Autopsies indicated the sisters had been raped and before they were killed, their toenails had been removed. Salima theorized that they had refused to cooperate. "To write so openly about this was as dangerous as anything a journalist could do," writes Bennoune. And then to demonstrate her point, she quotes the brave journalist: "Their faces, serene in death, must have been twisted by intolerable pain for hours from the torture...of collective rape to which they were subjected by barbarians who claim to act in the name of Islam."

Bennoune's interest in Algeria is personal. Her book was inspired by her father's experiences in Algeria in the 1990s when, as a progressive intellectual of Muslim heritage, he risked his life by campaigning against Muslim fundamentalism. Bennoune is outraged that Mahfoud Bennoune and other Algerian democrats generally received little international attention or solidarity, including from the left. She is especially critical of western intellectuals who thought the democratic election of Muslim fundamentalists was somehow acceptable. "Democracy is a lot more than an election," she says. "Democracy is about free speech, debate and choice."

Another Algerian story concerns Amel Zenoune-Zouani, a third year a law student at the University of Algiers. In 1997, members of GIA (Armed Islamic Group) in Sidi Moussa where Amel lived posted placards telling young people to stop studying and to stay at home. Returning to her home, Amel was pulled off a bus and immediately murdered in front of her friends as a warning. They slit her throat. Then they told the other passengers: "if you go to the university, the day will come when we will kill all of you like this." Bennoune takes her time telling us this story, weaving commentary between interviews with Amel's family. It is obvious that she identifies with this law student, since she herself is currently a professor of international law at the University of California, Davis.

Bennoune's long experience does not make her immune to the horror she hears.

"The case that makes me crumple at my desk, " she writes in chapter 6 about Iran, "is that of a young girl in Tehran." She then tells the story about the girl's arrest in 1981 for swimming in her home pool in a bathing suit. Evidently, she was found guilty of causing a state of sexual arousal in a neighbor from whose house she could be seen. She was sentenced to 60 lashes but died after the 30th lash.

Women's human rights defenders -- not all of whom are women but include many men as well - say it is one of the most important forces contesting political Islam. "Every step forward for women's rights," argues Nigerian sociologist, Zeinabou Hadari, "is a piece of the struggle against fundamentalism." Bennoune also quotes American writer Katha Pollitt: "The opposite of fundamentalism is feminism."

It might be inappropriate to call a 342-page book about atrocities a page-turner, but this one is. You might not agree with every comment and conclusion Bennoune makes but her message cannot be ignored.