The word "speculator" has often been conflated with "entrepreneur," and both of them tarred with the brush of "con men."

However, there is a good connotation for entrepreneurs. They are viewed as risk-takes who create new products and businesses. Speculators are seen as risk-takers solely out to make money.

But is speculation really a bad thing? How do economists view speculators? Here's how one economist sees them.

Perry Mehrling's Money and Banking Class

Perry Mehrling, author of several books, the latest of which is The New Lombard Street, is professor of economics at Barnard College in Manhattan. Mehrling has been offering a free online course on money and banking.

His goal is to teach anyone at Barnard or elsewhere in the world how to read and understand the London Financial Times newspaper in its entirety.

This class is not like any other economics course you'll find. Mehrling crosses a divide that at my alma mater, The University of Wisconsin in Madison, was physical as well as curricular. On one side of the street was the economics building. On the other side was the department of finance. Never did students or faculty of either department cross that street.

But now there is Mehrling. His course seamlessly combines economics and finance. He offers video lectures, weekly discussions, quizzes, readings, and exams. You feel like you are back in college even if you're sitting at home, miles away from New York City.

Mehrling's underlying premise is that there is a "hierarchy of money" (gold, national currencies, bank deposits, and at the bottom -- securities, loans, and credit).

Different kinds of money and the relationships among them define each of our financial institutions.

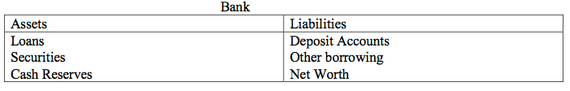

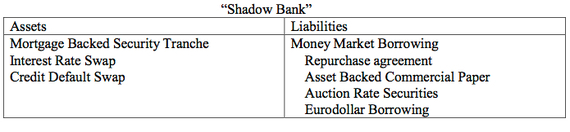

For example here's how their balance sheets distinguish banks from shadow banks:

Mehrling shows the plus and minus action on each side of their balance sheets as the different parties interact with each other. Usually their transactions all cancel each other out (i.e., they balance) -- but not always.

For example, middlemen ("dealers") in foreign-exchange transactions make money on the interest rates and fees they charge while hedging against their own risk if a currency rate changes drastically. In this way currency exchange dealers help keep international business flowing.

But speculative dealers who hedge the currency dealer's bets take on the full risk - when they lose, speculative dealers have to eat their liabilities. They can't hedge their bets and pass on the risk they take - the buck stops with them. This is why they are called "naked" speculators.

However, without naked speculators, the buck and every other country's currency wouldn't get exchanged. Matched-book dealers, those with balanced balance sheets, couldn't risk exchanging currencies. International trade could grind to a halt.

What's wrong with speculators?

As I understood Mehlring's lecture, AIG acted like a naked speculative dealer when it sold a 10 billion dollar CDS (credit default swap) to Goldman Sachs. That's because AIG carried no offsetting assets to hedge against this liability.

AIG was convinced this transaction with Goldman bore no risk to itself -- even as it guaranteed Goldman that it would pay the money in full if AIG's credit rating was lowered. And that is exactly what happened. Moody's lowered AIG's rating.

At the kick-off of the 2008 financial crisis AIG had to pay $10 billion to Goldman that it didn't really have. AIG's balance sheet didn't balance, and the Fed chose to bail out this deeply-indebted company. That was the start of massive bailouts by the Treasury Department.

In what sounds like a devil's bargain, Merhling suggests the way to take taxpayers off the hook for footing the bill for private banking is for the Fed to become a derivatives dealer itself and take the other side of the naked bets made by private derivatives speculators. This means the government would become a "lender of last resort" for private dealers.

To deter private dealers from needing government loans to pay their bills on time, dealers, particularly naked speculative dealers, would be required to have adequate capital flows to fully absorb the losses they might incur.

Apparently, naked speculators are necessary to grease the wheels of business in a hybrid (private and public) monetary system like ours. But this means taxpayers remain at risk of paying dearly again if speculative dealers can't pay what they owe on time. Perhaps it's time to give Perry Mehrling's ideas some thought.