Debbie Levy's terrific new book for children about Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg is called I Dissent. In an interview, Ms. Levy talked about what dissent is, when it's important, and how to get along with people even when you're dissenting.

What is dissent and why is it important?

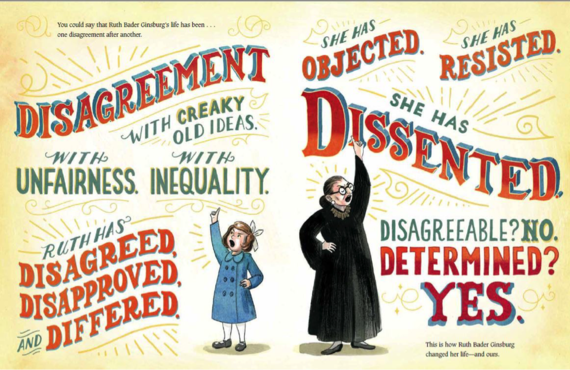

What is dissent! Dissent is saying "no." Dissent is disagreeing. It's disapproving. It's differing, objecting, resisting. . . .

Why is it important! It's how we make change, in our own lives, and the lives of others.

How can we tell when to dissent and when to compromise?

This is a great question, and one that I'll be exploring with young readers when presenting I Dissent in schools. The first step, I think, is thinking about when the expression of dissent is important, and when expressions of dissent may be pointless, or more hurtful than helpful. If I may quote Justice Ginsburg:

"Sometimes people say unkind or thoughtless things, and when they do, it is best . . . to tune out and not snap back in anger or impatience. . . . Anger, resentment, envy, and self-pity are wasteful reactions."

The point is, not every wrong needs to be righted, or even called out.

But then there are the wrongs that cry out for disagreement--bullying, bigotry, spreading falsehoods, denying rights, to name a few at the top of my list. Here, principle takes precedence over mere politeness, and yet I think RBG's example--of politeness!--shows the most desirable way to disagree and make change in our society. That is, there's disagreeing and there's disagreeing, as we've been made way too aware in this political season. There's flailing, insulting, divisive disagreeing. Not to mention willfully uninformed disagreeing. And then there's RBG's way: disagreeing by offering insight, not invective. Benefit of the doubt, not bashing. Is it any wonder that I think RBG is a great person to introduce to young people in a picture book?

As for the question of compromise, I'll pull out another favorite RBG quote, one I like so much it's on the back of the book jacket: "Fight for the things that you care about. But do it in a way that will lead others to join you." Sounds simple, but there's no question that second sentence is so hard to pull off. That's where compromise comes in.

What experiences did Justice Ginsburg have as a child that taught her the importance of dissent?

Oh my goodness. Plenty! My book shows her facing one such experience after another--and that is why, as the very first sentence says, "You could say that Ruth Bader Ginsburg's life has been . . . once disagreement after another."

To wit:

•"She disagreed" (when, on a car trip with her parents, she saw a sign that read "No Dogs or Jews Allowed!").

•"She protested" (as a schoolgirl, to being forced to write with her right hand even though she is left-handed).

•"Ruth objected" (also in school, to the rule that required girls to take home ec, reserving shop class for boys).

Little Ruth Bader was on her way to becoming the Ruth Bader Ginsburg we know today.

Why do judges who dissent explain their reasons?

Justice Ginsburg published a very interesting article (originally a speech) in the Minnesota Law Review in 2010, "The Role of Dissenting Opinions." In it, she quoted Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, who wrote, "A dissent in a court of last resort is an appeal . . . to the intelligence of a future day, when a later decision may possibly correct the error into which the dissenting judge believes the court to have been betrayed." The point is, dissenters explain their reasons in the hope that, somewhere down the road, future courts will adopt their reasoning and the dissenting view will be adopted as the law.

A dissenter may also explain her reasoning with a more immediate audience in mind, such as Congress. This is exactly what Justice Ginsburg did in her dissent in the famous 2007 Lilly Ledbetter case. She strongly believed that the court's majority was interpreting Title VII of the Civil Rights Acts incorrectly. At the end of her dissent, she wrote, "The ball is in Congress' court," and Congress heard her. The Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act became the first law signed by President Obama and it changed the law in the manner that Justice Ginsburg had hoped for in her dissent.

When judges disagree, do they get mad at each other?

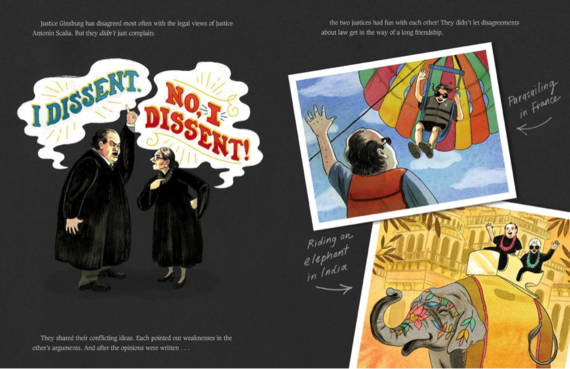

Maybe some judges do. But one of my favorite parts of I Dissent shows that they don't have do. Justice Ginsburg and the late Justice Antonin Scalia disagreed deeply and widely on all manner of legal issues. They shared their conflicting ideas. They pointed out weaknesses in the other's arguments. But, however improbably, they managed to be the best of friends.

How could she be friends with a Justice who disagreed with her so much?

She admired his lively and penetrating mind. They shared a love of opera. And she liked his sense of humor--as she said after he died, he had the "rare talent to make even the most sober judge laugh."

How did you teach your children about dissent?

First, where: at the dinner table. As for how: we had wide-ranging conversations about the news of the day, about school, about everything. (Confession: there were times when we thought perhaps we taught them to dissent too well.)

Did Justice Ginsburg ever inspire you to dissent?

Well, I was probably dissenting before I even knew who she was, and before she was a judge, much less a Supreme Court justice. But I would say that after working on this book and learning more about RBG, I find myself more likely to call out injustice and intolerance and bigotry where I see it.