It is well-known that women have curious powers to induce men to hysteria (think of Rick Santorum's apoplexy during a Senate debate about abortion) or violence (think of ankle peeking past burka's hem). Less well-known is the power of promiscuous female flies to induce scientists to apparently self-deceptive blindness to scientific facts. To illustrate my point, please consider the curious case against a plot in Angus John Bateman's influential 1948 study of how sexual selection (the process that results in fancy male traits like the peacock's tail) works. The study provided, for the first time, an experimental justification for the double standard and the evolution of bad-boy masculine behavior and good-girl feminine behavior, also known as the adaptive justification for "sex-crazed guys" and "gold-digging gals."

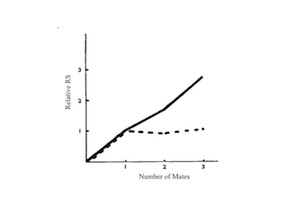

Bateman asked two questions of adult fruit flies in small populations: Who mated with whom? How many offspring did each subject have? Once he had estimated the number of mates for each subject and their number of offspring, Bateman graphed the number of adult offspring against their number of mates (i.e., reproductive success, or RS) so that he could compare the curves for females and males. He made two graphs of RS against number of mates. In the plot below, the average RS for males (the solid black line) increased with the number of mates. For females, RS (the dotted curve) was flat, showing no increase with number of offspring after females mated once.

Graph reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd. License Number: 2960430598991. From Bateman, A. J. 1948. Heredity (Edinb) 2:349-368, Figure 1b, p 362.

From this plot he concluded that males earned fitness benefits from mating with more than one mate, but females did not. The graph says that females gained no additional offspring (RS) from mating with more than one mate, but males did. There seemed to be no fitness payout to females who mated with more than one male. For the first time there seemed to be a compelling answer to the evolutionary question of why "there is an undiscriminating eagerness in the males and a discriminating passivity in the females."

Bateman then argued that this made sense given what Darwin had seen: males duking it out over access to females, and females seeming to prefer to mate with some males more than with others. Bateman's paper provided, for the first time, experimental evidence that Darwin was correct. It seemed that reproductive competition among males occurred, and winners had more offspring. Furthermore -- so went the logic -- because females got no rewards in terms of fitness (number of offspring), selection did not result in females being sex-crazed like males but very careful (choosy) about with whom they would mate.

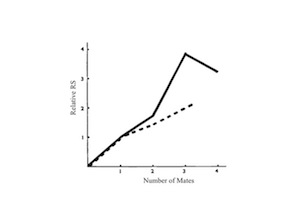

But despite these pat conclusions, there's more to this story. Bateman and apparently many of his readers did not take so seriously his other plot (below) showing that female number of offspring ("Relative RS" on the vertical axis) did increase with number of mates, not as steeply as for males but still enough to suggest that Bateman actually had the first evidence that females had more offspring when they mated with more than one male -- distinct evidence contrary to Bateman's own famous conclusions about females and multiple mating.

Graph reprinted with permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd. License Number: 2960430598991. From Bateman, A. J. 1948. Heredity (Edinb) 2:349-368, Figure 1a, p 362.

In this light, consider Bateman's conclusions again.

There is an undiscriminating eagerness in the males and a discriminating passivity in the females [because] with intra-masculine selection males will be expected to show polygamous tendencies, whereas in females there would be selection in favour of obtaining only one mate after which they would become relatively indifferent.

It just doesn't jibe; females did earn fitness rewards from mating multiply, according to Bateman's second plot! Should we go back to the drawing board?

In Bateman's paper the two graphs appear side by side. Why had he not used the plot just above to inform his conclusions? This was the plot with the most data, in which the adults had no history of inbreeding and more background genetic variation than the flies in the other plot. Why did he seem blind to the graph in which female fitness increased when they had multiple mates? More importantly, why did readers fail to notice the implication of Bateman's "benefit of polyandry" (female multiple mating) graph? If others had noticed, why didn't they say something? And if previous readers were blind to it and Bateman was blind, too, where did the collective blindness come from?

Was there a plot against the plot? Two things point to "yes." As scientists Zuleyma Tang-Martinez and Brandt Ryder of University of Missouri at St. Louis argued, the first plot above was the one Bateman seemed to like best because his conclusions depended on it. Bateman ignored the results in the plot showing that females who mated with more than one male also had more offspring, a result in Bateman's paper that challenges Bateman's conclusions about females. In addition, some modern textbook writers published only the graph showing that females mated with but one male, dismissing the graph showing that females get fitness rewards for mating with more than one male. One couldn't be faulted for claiming a conspiracy.

However, I favor the hypothesis that Bateman was self-deceived rather than knowingly deceptive and that textbook authors who promoted Bateman's conclusions to student readers were gullible, perhaps uncritically gullible. Collective deception? Perhaps. Whatever explanations account for lack of skepticism nevertheless raise important questions about why it took so long to do a strict repetition of the original study.

Further reading:

Bateman, A. J. 1948. "Intra-sexual selection in Drosophila." Heredity 2: 349-368.

Dewsbury, D. A. 2005. "The Darwin-Bateman paradigm in historical context." Integrative and Comparative Biology 45, no. 5: 831-837.

Hrdy. Sarah B. 1999. Mother Nature: A History of Mothers, Infants, and Natural Selection (Pantheon, New York), 1999

Tang-Martinez, Z. & T. B. Ryder. 2005. "The problem with paradigms: Bateman's worldview as a case study." Integrative and Comparative Biology 45, no. 5: 821-830.