Whenever the cause of Jewish social justice comes up, a lot of ink is dedicated to the life and actions of Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. Whether he was marching alongside Martin Luther King or protesting the Vietnam War, Heschel's work and erudition remains the standard for Jewish activists to emulate. But, does anyone remember if there were rabbis or other Jewish leaders marching and organizing in solidarity with the Cesar Chavez and United Farm Workers?

This is a forgotten story.

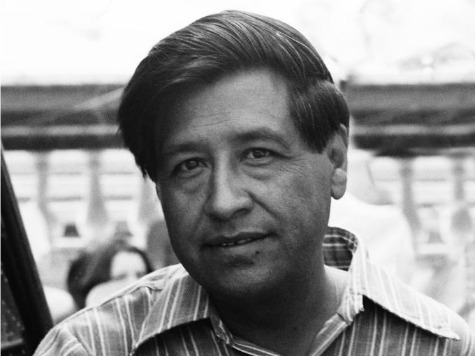

Chavez was born in Arizona, but he spent most of his early years toiling with his family as migrant workers in California, an experience that gave him first-hand knowledge of his future calling. In 1952, the civil rights activist and organizer Fred Ross met Chavez and soon realized his potential for organizing farm workers.

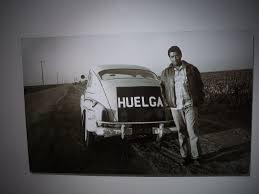

The subsequent struggle by Cesar Chavez and the UFW to unionize farm workers has a long, arduous history: many still remember the rallying cries of Huelga (Struggle!) and La Causa (the Cause) from the 1960s and 1970s. It was most closely associated with California and wine and table grape growers, and frequently pitted nonviolent farm workers against Teamster goon squads, which often negotiated secret sweetheart deals with big growers in an attempt to defeat the UFW through intimidation, both physical and psychological.

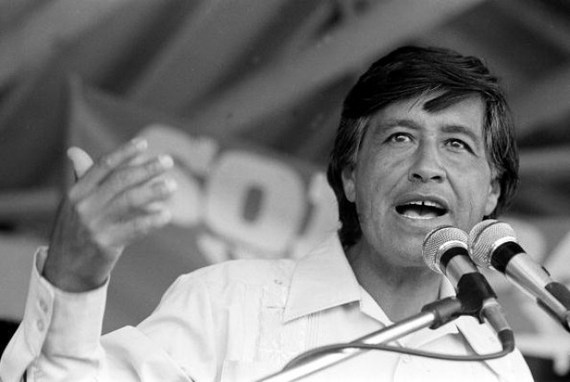

While several small unions had coalesced and organized in the early 1960s, in 1965 the farm worker struggle took off with the Delano Grape Strike, a five-year effort to unionize California winery workers. Early political support from national union leaders and Senator Robert F. Kennedy helped bolster the movement, but the steadfast, nonviolent tactics promoted by Chavez and others, including a 340-mile march from Delano to the state capitol in Sacramento, were critical in keeping the movement going. In 1967, the UFW initiated a boycott of California table grapes. In spite of the formidable political backing, Chavez now showed that the means as well as the ends were important. In 1968, Chavez protested an effort by some strikers to use violence by going on a twenty-five day hunger strike, which debilitated him for much of the succeeding year.

The 1970s were years of turbulence and exhilaration. In 1970, when the UFW largely prevailed in negotiating new contracts with the grape growers, lettuce growers countered by signing with the Teamsters, causing more strikes and violence. Chavez was jailed for refusing to call off the strikes.

In 1972, the union organized Florida citrus workers, defeating an attempt by the Nixon administration to restrict its activities, and affiliated with the AFL-CIO as the United Farm Workers of America. Meanwhile, in Arizona, the legislature passed a law that outlawed virtually any farm labor activity, including organizing or going on strike.

In 1973, wineries (including Gallo) signed contracts with the Teamsters without labor election or notification. During this struggle, 3,500 strikers were arrested, dozens were wounded and two people were murdered. In response, there was a further boycott of selected grapes, wine and lettuce.

In 1975, when Jerry Brown was elected governor of California for the first time, farm workers finally won the right to organize and engage in collective bargaining. While growers and some politicians--especially Republican governors--tried to negate or violate these laws, the UFW persevered with selective boycotts and organizing efforts. Later, Chavez dramatized the plight of farm worker exposure to dangerous pesticides by going on his last hunger strike in 1988. When Chavez died in 1993, farm workers nationwide were much better off than when he began his organizing efforts.

Any march for human dignity and fair wages is a Jewish cause. Who marched with Cesar Chavez? Who were some of the rabbis working in solidarity with him? Is there any scholarship exploring the Jewish relationship with the UFW? I know Orthodox rabbis who argued it was forbidden to eat grapes in the 1960s because of oppressive labor practices, but who was working more closely with Chavez?

As it turns out, many rabbis felt quite comfortable supporting Cesar Chavez's labor movement activism from their synagogues. Many came to support Chavez via the Civil Rights Movement and were already in control of mass organizational and outreach capabilities. Consider the leadership of Rabbi Joseph Glaser, who in July 1967 was one of three mediators who helped reach an agreement with the Teamsters that they would withdraw from the fields. Rabbi Glaser, as Executive Vice President of the Central Conference of American Rabbis at the time, was a long-time supporter, as evidenced by an article he wrote in 1986 for the UFW magazine Food and Justice. His topic was on the Biblical command, Thou shalt not oppress, which was

...violated daily,...by growers who treat farm workers with disdain and neglect born of greed and driven by arrogance. Elections are ignored, promises broken, agreements and judgments violated, lethal pesticides are strewn, often without warning... and violence sheds blood and tears. It is oppression--un-G-dly oppression.

But farm worker support was not exclusive to one stream of Judaism. Orthodox rabbis, like Rabbi Samuel Korff of the Boston Beit Din and Rabbi Haskel Lookstein of the Upper East Side, urged their communities not to buy non-union grapes due to the oppressive conditions. They argued they were forbidden because of oshek, the exploitation and abuse of workers.

In addition to rabbis, there were other Jewish activists who joined Chavez's struggles: Jerry Cohen, a labor lawyer who led the UFW legal staff, and was beaten savagely by Teamster goons in 1970; interfaith pioneer Rita Semel; progressive agitators Heather and Paul Booth; as well as countless other holy participants whose stories have not yet come to light.

Marshall Ganz, the son of a rabbi, had come from the civil rights struggle in Mississippi before becoming a volunteer and long-time organizer for the farm workers. He shared this with me:

The first "official" engagement of Rabbis that I recall was during the Lenten March to Sacramento in 1966 when a team of Rabbi's visited the marchers, brought Matzot and explained Passover in terms of the Last Supper, as well as Exodus. When we moved to the boycotts, beginning in 1966, there was also strong Jewish support in the various cities, the example you're thinking of, the Boston Board of Rabbi's decision, led by Rabbi Judah Miller, that grapes were oshek -- unclean as the fruit of exploited labor.

Ganz shares that Jewish support was not only on the activist side but also on the employer side:

A little known fact as well in each of the agricultural industries that we organized, Jewish employers were the first, and, in some case, very very first, to sign. The first wine company to sign with us, or first contract, was Schenley Industries, run by Lewis Rosensteil (with mediation by Sidney Korshak), the first table grape grower to sign with us was Lionel Steinberg, the largest grower in the Coachella Valley, and the first vegetable company to sign with us, Interharvest, a subsidiary of United Brands (former United Fruit Company) run by Seymour Harris and XX Black.

He also noted that Jews also paid a human cost in the struggle:

The first person to lose their life on a farm worker picket line was Nan Freeman, a 17-year-old college student, volunteer from Boston, who joined our efforts in Florida, a strike of Talisman Sugar Company, and was killed by a truck crashing the picket line.

Ganz shared that he took Chavez to Yom Kippur services on several occasions and also joined him at some Christian services. Additionally, Chavez was invited by other Jewish organizations to speak at rabbinic conventions, Passover seders and High Holiday services.

Marc Grossman, who worked with Chavez during his final years as his press secretary, speechwriter and personal aide, shared that "Rabbis played key roles rallying support for UFW strikes and boycotts....

Cesar's wife, Helen Chavez, tells about how, after the union first attracted national news coverage in late 1965, Helen and her sister Petra were opening envelopes that were pouring in with donation checks. Petra, looking at the checks, said, "Hey sister, look: All these people have the same first name, Rabbi." Helen explained a rabbi is like a priest. The first institutional religious support for the UFW came then when boards of rabbis in big Eastern cities declared boycotted products non-Kosher...I especially remember frequently being with Cesar and Rabbi Sidney Jacobs with the Southern California Board of Rabbis.

Chavez, who had resisted offers to have a biography written of him, nevertheless agreed to have an "autobiography of La Causa" written because it would contain the words of many of those involved in the struggle. The writer chosen was Jacques E. Levy, a journalist who came from a wealthy Jewish family, spoke no Spanish and considered himself an atheist. Nevertheless, he was not only the author/compiler of Cesar Chavez: Autobiography of La Causa, but he functioned as a secretary and quasi-press department for the union, drove people to meetings and demonstrations and was even beaten by Teamster thugs for his efforts. Levy first met Chavez in 1969, and was struck by the labor leader's "sincerity" and, uncharacteristically for a labor leader, "gentleness." After six arduous years of interviews and work, as he finalized his book, Levy mentioned to Chavez that "truth" was his weapon. Chavez replied affirmatively, expressing his view that eventually the workers would win: "Truth is nonviolence. So everything really comes from truth. Truth is the ultimate. Truth is God."

The world that Chavez struggled to achieve is far from its goal. Even today, there are shocking examples of mistreatment of farm and migrant workers by unscrupulous growers. Jewish social justice groups around the world are responding to various manifestations of these injustices. The Coalition of Immokalee Workers, which works to expose and correct these practices, reports that since 1997, nine separate prosecutions for slavery have been brought against growers, mostly in Florida tomato fields, where a majority foreign worker force is beaten and forced to work as farm laborers. In response, some rabbis from T'ruah have visited Immokalee since 2011, and have continually called on retailers to insist that tomato workers and others be treated and paid fairly (through initiatives such as the Campaign for Fair Food), publicizing their campaign to abolish modern slavery.

With globalization minimizing the distance between disparate communities, and the overarching collusion of industrial elements to render unions impotent, the pressing need for like-minded tribes to unite is more important than ever. To be the vanguard of guarding the rights of the vulnerable is to be a righteous individual. This is why the hidden link between the work of the Chavez and the UFW and the Jewish community is significant and critical. As people dedicated to equity and fairness, we look to moral leaders who have the sense to dedicate their lives, indeed possibly their livelihoods, in the name of justice. From the humble fieldworker to the politically connected activist, we all have a role to play in protecting vulnerable populations from exploitation. Let us continue to build on their work and expand their visions of the world, where people are treated fairly no matter their stature in life.

The Jewish community should be proud of its modest but significant investment in the farm worker struggle and should continue to strengthen the Jewish-Latino relationship today and to collaborate for worker justice. Throughout history, Jews have been on the front lines advocating for justice. Today, with unprecedented freedom yet new systems of oppression, we must double down our efforts to stand with the most vulnerable in our societies.

Rabbi Dr. Shmuly Yanklowitz is the Executive Director of the Valley Beit Midrash, the Founder & President of Uri L'Tzedek, the Founder and CEO of The Shamayim V'Aretz Institute and the author of seven books on Jewish ethics. Newsweek named Rav Shmuly one of the top 50 rabbis in America."