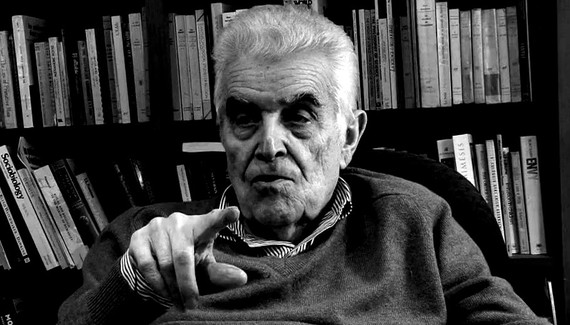

This weekend, French philosopher Rene Girard died at his home in Stanford, CA, at the age of 91. Girard has been one of the most seminal thinkers on war and peace, religion, culture, and sociological study in the last century and though his best works were, of course, many years behind him at the time of his passing, he will remain one of the proverbial shoulders that future thinkers will stand on.

Girard was originally a literary theorist - I first heard of him while doing graduate studies in Literature - as much as a historian and anthropologist. In 2005, he was elected to the prestigious Académie Française and at one point was called the "Charles Darwin of human sciences." It was at Fuller Seminary, however, that I was turned towards his part in contemporary theological studies.

Looking at patterns across historical cultures, Girard had noticed a the prevalence of "scapegoating" or ceremonially placing communal indiscretions onto one person. This is so prevalent today that our ears are likely deaf and eyes blind to it when it happens. A celebrity who kisses the nanny and divorces their spouse is, in some sense, hated all the more not because of what they did but because their behavior embodies "everything wrong with the world," even our own longing for adventure. Girard's unique perspective, focused through years of studying literature, mythology, and religious texts, saw scapegoating behavior as imitative or "mimetic." That is, once the needs of survival are met, humans begin to develop wants that are shaped communally, in emulation of one another. This always leads to competition - indeed, competitive desire is the primary assumption of Western economics.

Girard believed competitive desires and behaviors would always lead to the unravelling of society, perpetual anarchy, unless society achieved that initial balance by pooling their animosity towards one person. In many cases, this means the reduction of ethnicity, beliefs, or political behavior to "those people" or, too often, the victim who - despite all evidence - "had it coming" because of their skin color, religion, or sexual orientation. The supposedly offending party, the "scapegoat" allows a mental, emotional, and spiritual distance to project one's own fears and failures through the collective "us" towards "them." In other words, as individuals in a community become homogenized and more similar, there is no threat of difference, necessitating an "other" who we can collectively gang up on. Communal anger is validated once we seize upon what Girard would call a "founding murder" - a seminal event, real or imagined, that victimizes those of us in the group. In religion and ancient plays, this is acted out on stages and in pulpits. The literal symbolizes the metaphorical in ritual; this was, after all, the role of ancient religion: to embody a belief and create shared (or rather, diffused) responsibility among the sacrificers. For Girard, "scapegoating" was sacrifice in its traditional form. It was the way a community came together and stayed together, denying their own culpability to instead project it on to the victim, who was aways guilty.

For Girard, however, there was a sharp change with the death of Jesus. Girard converted to Roman Catholicism in the early 1960's after reading the works of Dostoevsky and was so until his death last weekend. Because of his conversion experience, Girard's great attention to history and literature turned towards the role of sacrifice in religion and specifically how the role of sacrifice in Christianity played out in Western ideologies. He began to notice that while many cultures were bound together by a shared belief in the guilt of the victim, Christianity reversed this; the innocent in the ritual was no longer the community. The innocent person was the victim. The Hebrew prophets of the Babylonian period who blame the Israelites and exonerate their oppressors are a strong example, as well as Paul's reading of the sacrifice of Jesus, the innocent one, and the sinful state of all peoples involved in his murder.

Brought to bear on the Modern Century where war was such a prevalent part of life, Girard came to believe that the advocates of war saw their activities as a way of regulating and limiting violence. It was, he said, a myth that violence could be redemptive - that atrocities must be committed to prevent further atrocities. In this, war was functionally justified by those in power. Those who protest wars, for Girard, were the ones who saw clearly that violence was, in the final analysis, a casting off of restraint and not the divinely sanctioned "justice" of those in power.

As his work developed over the subsequent decades, Girard went on to argue that his initial impressions were incorrect. Religion did not lead to violence, rather violence created a need for religion to channel and sanction the use of force. It was an idea picked up quite dramatically by religious scholars, including Karen Armstrong. Religion makes violence both acceptable and palatable and continues to do so in various forms from subtle shaming to the intense missions abroad. That I began reading Girard at the height of the war in America's deployment in Afghanistan and Iraq, I suppose, crystallized his later insights teachings for me and makes his recent passing feel all the more a loss for philosophical thought and religious studies. He has helped many recontextualize violence and the role of violence in religion in historical practice.