If the so-called "foreclosuregate" scandal says anything, it is that efforts at achieving financial reform are not complete. A critical question remains: did the financial reform legislation that was passed fully address the root causes of the present financial crisis? Case in point: the first phase of financial reform came and went, yet the Dodd-Frank legislation said next to nothing about reducing the growing income inequality in the United States. Should it have? If the mammoth legislation was designed to fill in the holes in the regulatory landscape, and prevent future disasters from occurring, it should have taken a look at income inequality as one of the causes of the crisis, and attempted to address such inequalities as a means of ensuring we do not repeat the mistakes of the past.

Even if Dodd-Frank does little to combat income inequality, legislation currently pending before Congress would strengthen the Community Reinvestment Act--probably the only piece of the financial regulatory infrastructure that deals with income inequality head on. October 12th marked the 33rd anniversary of passage of the CRA; Congress should pass legislation currently pending in the House, the American Community Investment Reform Act of 2010 (ACIRA) as soon as possible in order to ensure that low- and moderate-income communities have access to credit on fair terms. If financial reform is to address income inequality adequately, such equal and fair access to credit--which the CRA is designed to promote--is one of the best ways to try to reduce those inequalities, and stave off future crises.

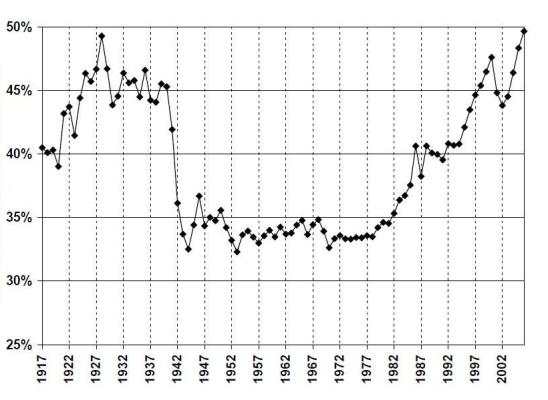

In all the debate over financial reform, few in Congress have raised questions about the impact of growing inequality on the very crisis that brought about the need for this reform. So what role, if any, did income inequality play in the lead up to the Great Recession? The answer to that question is unclear, but we do know one thing. The share of wealth in the U.S. enjoyed by the top 10% of income earners saw two large increases over the last one hundred years: first, in the lead up to the Great Depression; second, in the lead up to the present Great Recession, as the following graph shows.

Table One: The Rich Get Richer

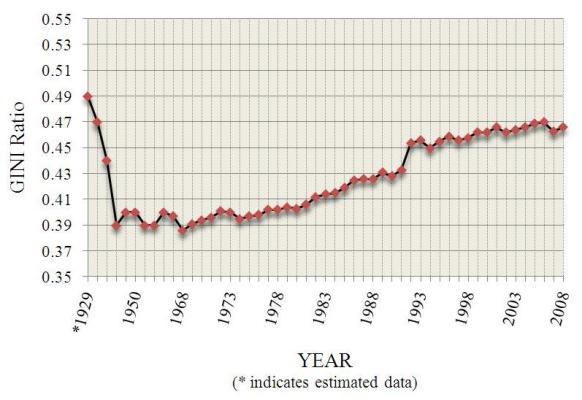

Similarly, income inequality in the U.S., as measured by the GINI coefficient, (3) the difference between the wealthiest and least wealthy in society, follows a similar trend.

Table Two: U.S. GINI Timeline

How does the U.S. GINI ranking compare to that of other countries? The peer group of the U.S. in terms of GINI scores includes Ghana, Turkmenistan, Senegal and Cambodia.

If there does seem to be some correlation between income inequality in the U.S. and financial catastrophes, what, if anything, does Dodd-Frank, the 2000-plus page financial reform legislation that passed in Congress in July of this year, say? Very little, in turns out. Section 1204 of the bill, entitled "Expanded Access to Mainstream Financial Institutions," authorizes the Secretary of the Treasury to provide grants to initiatives designed to improve the access to legitimate bank accounts for "low- and moderate-income individuals." Admittedly, the new Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection will, no doubt, provide much needed protection for low- and moderate-income communities, to monitor abusive lending practices and harmful financial products. There are also new "say on pay" provisions that give shareholders the ability to generate non-binding votes on executive compensation packages in companies covered by the law.

Since Dodd-Frank does little to combat income inequality directly, the CRA appears to be one of the few pieces of federal financial legislation that addresses the issue. Under the CRA, federal bank regulators use their regulatory powers to "to encourage [financial] institutions to help meet the credit needs of the local communities in which they are chartered." This goal must be achieved in ways that are "consistent with the safe and sound operation of such institutions."

Originally adopted in 1977, Congress designed the CRA to combat two practices thought to undermine the financial health of low- and moderate-income communities: redlining, the practice of refusing to bring services to certain communities; and capital exportation, the failure to use consumer deposits from a community to provide access to credit to customers in that same community. In addition, the requirements of the CRA were seen as a quid pro quo for deposit insurance, that essential federal financial backing given to commercial banks without which many would likely go out of business.

Despite its relatively benign purposes, the CRA has been the target of conservative attacks, basically from its very inception. These attacks have become particularly shrill since the financial collapse, with many levying charges that the CRA was to blame for the crisis because it allegedly forced banks to make risky loans to risky borrowers from low- and moderate-income communities. Unfortunately for these arguments, they are pure fantasy.

As stated earlier, the CRA was designed to prevent redlining and capital exportation, and to serve as one of the costs of federal deposit insurance. As a result, the CRA only covers financial institutions that take deposits. It simply does not apply to non-depository financial institutions, and the overwhelming majority of subprime lenders were, in fact, non-depository institutions. Indeed, in 2007, 169 subprime lenders failed. 167 of them were non-depository institutions and not covered by the CRA. A number of other critical loopholes made the overwhelming majority of risky lending beyond the reach of the CRA: in fact, a study by the Federal Reserve found that 94% of subprime lending during the height of the subprime mortgage frenzy was beyond CRA coverage.

Now that Congress has passed Dodd-Frank, it is poised to take up the issue of strengthening the CRA through ACIRA. Just weeks ago, ACIRA was introduced in the House of Representatives. This legislation is designed to close the CRA's loopholes by imposing CRA obligations on a range of financial industries, including those non-depository lenders that caused such havoc in the events that led to the present financial crisis. It also gives federal regulators stronger tools to ensure covered financial institutions meet their CRA obligations and offers strong avenues for community participation in the CRA enforcement process. The bill enjoys support by a coalition of over 260 organizations, led by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

Each of these reforms is necessary to strengthen the CRA's ability to protect the access of low- and moderate-income communities to financial services. Such access is critical to guarantee that the full range of financial services reach the low- and moderate-income communities that were largely unable to reap the bulk of the benefits from the go-go days of the last decade, the fruits of which were mostly reserved for the wealthiest. Nevertheless, those same low- and moderate income communities seem to be paying the tab for what economic expansion that did occur. The reforms proposed through ACIRA will go far in ensuring that future economic expansion will not leave behind the communities the CRA is designed to protect. Requiring all financial institutions to meet the credit needs of these communities places much needed tools in the hands of regulators, as well as the very communities the CRA is designed to protect, to guarantee that all communities, regardless of their relative wealth, can gain access to credit, the lifeblood of any economic activity. Given the need for the reforms ACIRA would accomplish, Congress would serve the American people well by passing it, without delay or hesitation.