It was hardly the weather for a suicide. Students had gathered at Collegetown Bagels -- a popular watering hole on days like October 8, 2008, when the Ithaca sun makes an unseasonable appearance -- and from the outdoor patio, you could make out the lofty spire of McGraw Tower, poised now to chime two o'clock. At one minute before the hour, a pair of students crossed the stone bridge to class, the college town behind them, Cornell University ahead, and the deep gorge ninety feet below.

Across the street, an elderly woman was coming the other way. A lanky man in a navy track jacket walked briskly a few paces behind, his face obscured by a white cap. Back in town, a sophomore was feeding a parking meter, when she saw something from the corner of her eye. The man had stepped onto the bridge's western parapet. "I can't look!" someone ahead exclaimed. Up on the bridge, the older woman turned to find anyone who had just seen what she'd seen.

By the time the dean of students, Kent Hubbell, arrived, a small crowd had gathered around the bridge. One man walking through the gorges had his camera handy, and snapped four pictures of the body, which, within thirty minutes or so, was removed by emergency workers. Soon the crowd cleared, and an hour later, the bridge reopened for traffic. "Life went on," remembered Hubbell. "It's amazing how quickly." As for the two witnesses on the bridge, they didn't even wait around to see what happened. "As soon as we heard someone calling 911," said one, "my friend and I continued to campus."

If people in Ithaca seem inured to suicide, that's because they are. For as long as anyone can remember, Cornell's gorges have furnished a wide open casket for those so inclined, and Ithaca, in turn, earned the unwanted distinction of "suicide capital of the combined Ivy League, Big Ten, Little Three, and Seven Sisters," as one local writer put it. Although commensurate with national averages, suicide at Cornell -- or to borrow the local vernacular, "gorging out" -- has become the stuff of myth. And sometimes reality, as this month, when the university lost three students -- in February, Bradley Ginsburg, 18; three weeks later, William Sinclair, 19; and the very next day, Matthew Zika, 21 -- in as many weeks to its precipitous gorges. The recent spate of suicides has cast a pall over the campus. "The cumulative effect of this loss of life is palpable in our community," said Susan H. Murphy, the university's vice president for student and academic affairs, in a video address. University staff, Murphy said, were knocking on student doors, and even stationed on the campus bridges.

But if suicide, as the adage goes, is a permanent solution to a temporary problem, then confronting suicide is just the opposite. While the problem abides, the solutions -- and the attention these tragedies occasion -- inevitably wear thin. Thus, in the fall of 2008, the suicide of Jakub J. Janecka. That day, when police asked the university if Janecka, 33, was an enrolled student, they were told no, but that he was an alumnus, now ten years past his date of graduation. From the small town of Honesdale, Pa., Janecka had recently completed graduate studies in Washington D.C. But what brought him to Ithaca, if not the end he found, no one was quite sure. And why Janecka -- or, for that matter, any of the young men -- came to the gorges to meet that end is a question best answered from the beginning.

In May of 1866, Ezra Cornell gathered his friends and backers to a site four hundred and twenty five feet above Lake Cayuga, the longest of New York's Finger Lakes. Most of the intended trustees -- including Andrew Dickson White, later the university's first president -- preferred a downslope site, but Cornell insisted on this rarified expanse. Cornell, generally a solemn man of few words, splayed his arms to the north and south and decreed: "Here on this line extending from Cascadilla to Fall Creek, with their rugged banks to protect us from uncongenial neighbors, we shall need every acre for the future necessary purposes of the University." And so between two gorges, Ezra Cornell built a great university.

Secluded by two natural barriers, Cornell University rose as an ivory tower of American academe. As the Alma Mater's intones:

Far above the busy humming

Of the bustling town,

Reared against the arch of heaven,

Looks she proudly down.

Nearly a century later, when an editorial in the Cornell Daily Sun asked, "So what is the spirit of Cornell?" it was the university's apartness they singled out: "It can be felt perhaps only by wandering through that metropolis of learning perched on a hill."

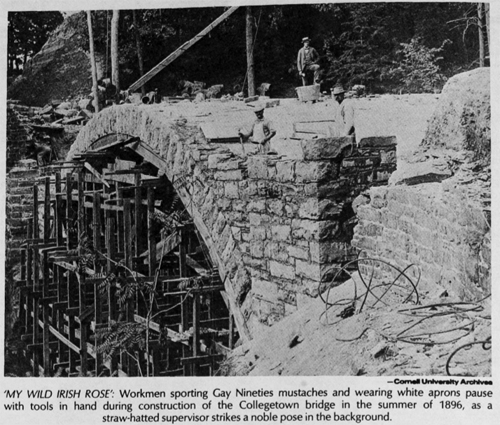

Within a few short years, the nascent school on a hill outgrew its southern frontier. As John Schroeder, a former writer for the Daily Sun who now serves as its full-time adviser, has recounted, to reach campus each morning, students in the inaugural class of 1868 had to negotiate a rickety footbridge that dipped into the Cascadilla ravine. In the summer of 1896, architect and alumni William Henry Miller drew up plans for a vaulted bridge of stone and earth. That bridge, now known as the Collegetown Bridge, opened for traffic -- and admiration -- on April 7, 1897. In the words of O.D. von Engeln, a professor of physical geography: "Continuing up the hill we turn to the left and come directly to the stone arch bridge over Cascadilla Stream. One may lean far out over the parapet of this bridge and look directly down on the rushing white current of the waterfall below known as the Giant's Staircase, many feet below."

From very early on, the specter of suicide haunted Ithaca's gorges. In 1889, an engineering student named Edward Wyckoff drew up plans for a suspension bridge to span the northern gorge, Fall Creek. When a professor failed his proposal, Wyckoff angrily withdrew from the university, and, as legend had it, threw himself into the ravine. In fact, Wyckoff never jumped, and a decade later financed the bridge's construction himself. His erstwhile instructor was vindicated, however, when a replacement was installed in 1961. Still, the rather tenuous bridge remains steeped in mythology: it's said a kiss shared at midnight will portend certain marriage, while one unreturned will collapse the bridge entirely.

Throughout the next century, suicides both real and rumored left a morbid blemish on the student body. On a January morning in 1940, when Douglas James Hill failed to show up for breakfast, his fraternity brothers became concerned. Hill's body soon turned up in Fall Creek, and was raised with the aid of a tow car and winch; the boy's father sent a business associate to accompany home his son's remains. Later that same year, Shirley Slavin arrived with her mother to enroll for freshman classes. After a few days on campus, she journeyed to the east side of Fall Creek, lingering for nearly an hour. In front of more than twenty witnesses, Slavin asked a passerby to hold her books and purse -- and then leapt 125 feet to her death.

Before long, bridge suicides inspired the occasional prank or allusion. On November 19, 1953, the Daily Sun offices received an anonymous tip: "I just saw someone jump." At about the same time, someone crossing the bridge discovered a moth-eaten topcoat, a pair of paint-stained men's shoes, two outdated textbooks, and a typewritten note. Police searched the entire night without finding a body. There was nobody to be found. A decade after, in his novel Cat's Cradle, alumnus Kurt Vonnegut wrote: "Or if the sun comes out, maybe I'll go for a walk through one of the gorges. Aren't the gorges beautiful? This year, two girls jumped into one holding hands. They didn't get into the sorority they wanted."

Rob Fishman appears on Ithaca's WHCU to discuss the Cornell suicides.

Fifteen years later, at midnight on March 10, 1968, a senior sat on the ledge of the Collegetown Bridge. After a patrol car passed by, he left, only to return again a half-hour later. After more than an hour, policemen and friends coaxed him down from the bridge, and tragedy was averted. In the following day's Sun, the near-victim was described as a "ruddy-faced 200-pounder." For the many that year who did suffer suicidal impulses -- or worse, mention in the next day's paper -- the city of Ithaca created a Suicide Prevention and Crisis Service, which was incorporated in 1969. That first year, the crisis phone line received 387 calls. Today, there are between 20 to 35 calls per day, or nearly 10,000 calls each year. Of course, as Deb Traunstein, the director of education, notes, many of the callers are overwhelmed with work or worried about their futures, and not in any immediate danger. But then not everyone who is feeling suicidal calls either.

By the end of 1973, the young decade had already seen eight suicides in Ithaca, seven associated with the university, and four in the gorges. For 1,000 lineal feet, said an internal memorandum circulated on October 29, 1973, cyclone fencing alone could cost $30,000; safety mechanisms on every bridge might run as high as $80,000. The memo came after a directive in August, when an administrator warned, "The principal effort should be made toward protecting the impulsive jumper or prankster -- one who may be depressed, see the opportunity and take it without really thinking about it." But with everything else in the budget, the university planning department felt, "If there is $70,000 or $80,000 to spend on life safety measures, it could be more effectively spent than on the bridges and gorge banks." By the decade's end, that wisdom would be called into question.

As it happened, only one student jumped over the next three years, and for a time the issue was put to rest. Then, in the spring of 1976, junior Judy Kram took her own life. Her father, a Cornell man himself, wrote to President Dale R. Corson on May 26, 1976, addressing the question of bridge safety. "In terms of the Cornell University atmosphere," said Daniel Kram, "these bridges, beautiful to many are to others like flames to moths, magnets to self-destruction, intentional or unintentional." They might be called an "attractive nuisance," Kram said, using legalese usually reserved for cases involving small children. He never heard back, and wrote again in July, "surprised and somewhat dismayed."

Corson responded the next day. "This matter has been the subject of investigation and study several times over the years, the last one having taken place in 1973." The issue had come before the University Senate, the Engineering and Architecture divisions had produced "considerable" design work, and there had even been consultations with agencies with "similar problems," such as the Niagara Park Commission, said Corson. Still, "we have yet to come up with a solution which would be a really effective deterrent to those individuals who suffer an apparent compulsion to self-destruct when in such surroundings." Of concern, according to the president, was a design that would be both "functional and aesthetically pleasing."

In October of that year, the vice president for planning and facilities wrote a memo to Corson entitled, "Suspension Bridge - Aesthetics vs. Suicide Deterrent." While the department took precautions against accidents, the vice president said, "We do not program our design effort for suicide prevention." On the other hand, he conceded, "Aesthetics are of great concern."

Making little headway with the university, Kram turned to the courts. In April of 1977, however, the Tompkins County Supreme Court ruled that the "state of the applicable law is such that this tragic problem is not susceptible to solution by the courts." Kram next took his case to the Board of Trustees, sending each trustee an article from the Ithaca Journal that reported six gorge suicides between 1977 and 1978. "wrong," Kram circled the statistic, "5 suicides, 1 accidental death, A Cornell Junior who fell off while 'fooling around'!"

By the following spring, the University Council noted in Kram's file, "I am afraid that he has become extremely overzealous on the issue." Sensing that there was "no possibility that Mr. Kram will give up his cause," the lawyer said, "I truly believe that a group of us must sit down and once and for all establish a University position on this issue."

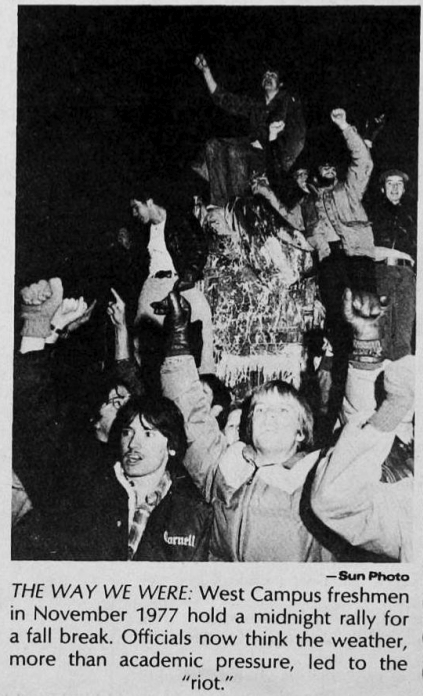

In fact, the university was at that moment facing a seeming contagion of suicides, eerily similar to this winter's spate. Schroeder, the Daily Sun adviser, remembers the ghastly autumn of 1977. "The sun never came out. It was drizzly and gray day after day after day." In quick succession, three students died in the gorges. Their classmates became despondent, and on a November midnight, staged an impromptu rally on West Campus. One by one, until they were 500, indignant freshmen yelled out into the night sky, "I'm mad as hell, and I'm not going to take it anymore," a catchphrase from the movie, Network. Cornell declared a mental state of emergency due to academic pressure, students formed a Committee for Humanism, and the Health Clinic opened a formal program aimed at suicide prevention -- one of the first at a college in the nation. A joint committee of the faculty and campus council voted for a fall break in October, which still exists today.

Yet by the next year, the crisis had abated. Fall term ended without incident; the director of the Suicide Crisis and Prevention Center joked, "We have certainly had a lot less business this year." Elmer Meyer, Jr., the Dean of Students, attributed the disturbance to "a lot of environmental downers last year, a losing football team, the bad weather." Dr. William White, who headed the Health Clinic, agreed: "The weather had a lot to do with the problem," he said. "All that greyness for two months even depressed me."

Alas, the calm was not to last. On April 13, 1979, about a month after sophomore Mark Sherman disappeared, his body was lifted from Fall Creek. Incensed, the boy's father, Irving, issued an open letter to Frank H.T. Rhodes, who had become Cornell's ninth president in 1977. "Mark had no history of emotional problems," Irving insisted. "He graduated from high school with the highest awards and he entered Cornell with excellent credentials. He came from a happy and stable family, had no social problems, and there were no obvious surface reasons for this tragic suicide." Among fifteen other loaded questions, Sherman asked Rhodes when Cornell will "realize that all the doctors and lawyers it spews out are not worth one human life?"

In the face of such accusations, one parent wrote in to defend Rhodes: "My god, the boy and his family deserve our sympathy and respect but are we right to crucify a man who has dedicated his life to helping young boys and girls?" Another parent, whose son was a friend of Sherman's, sent in a second open letter: "Mark told my son that whoever made the decision to allow him to return to school for this semester did so with the threat, 'If you f--- up this time, you're out!' Well Mark did f--- up, and he took himself out," wrote the parent, a practicing psychiatrist.

Although Rhodes replied sympathetically, he was in public defensive, and seemingly impenitent. "Students are adults," he said before an assembly of 100 students. "There is no way we can compel them to go for help." Privately, university administrators were far more callous in their appraisals. One of the deans, Alain Seznec, wrote to the vice provost, "I am afraid that the Sherman boy's case is the classic case of parental disaster: 'My boy will go to college and finish even if it kills him.'" As for charges of negligence, Seznec said that while Sherman's files "make for sad reading," he was "not left to his own devices, and was 'mothered' far more than most students." He added: "It is also clear he needed it."

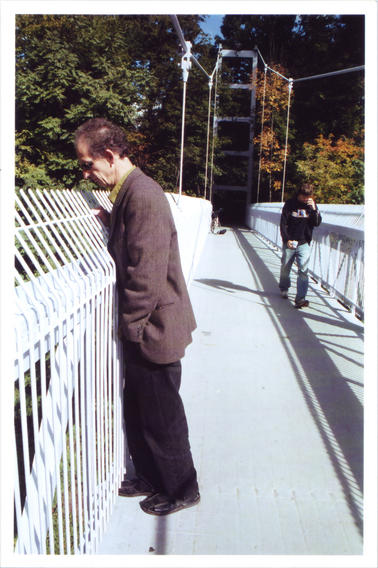

Still, there was enough concern in the community that in May of 1979, the university approved plans to add six-and-a-half foot metal bars to the already three-foot walls over the Collegetown Bridge. Schroeder spoke for many at the time when he editorialized against locking the "enriching and soothing vista behind anodized aluminum bars." In 1977, such barriers had been added to the suspension bridge over Fall Creek, which one professor described as a "claustrophobic channel with a honky-tonk garishness worthy of Las Vegas [where] serried ranks of close-spaced bars make a prison corridor." Another faculty member wrote disapprovingly:

Many people were and are truly depressed by the prison-like atmosphere created by the 'cure' applied to the suspension bridge...I do not take it as a given truth that saving one young (or old) life from self-destruction is to be weighed more heavily than the rare opportunity the suspension bridge once offered thousands of people every year to be immersed very closely in God's beauty.

Citing considerable outrage and opposition, the University announced later that month that plans for the suicide bars had been indefinitely suspended.

Oddly, a victim mentality persisted within the upper echelon of the university. In April of that year, a professor of animal physiology wrote to Rhodes, "I am sure that in the future suicides will be committed again at Cornell by students and by faculty members, but is each of us to blame except in John Donne's sense that the bell tolls for all of us?" When the next month, Channel 13 Eyewitness News ran a segment on the gorge suicides, one Cornell official complained that they were "singled out" because "our famous gorges...are so dramatic and photogenic." And after a student death in 1988, a university condolence letter reminded the grieving parents that "since 1970, there has been, on average, one suicide a year at Cornell," as if they might take solace in the statistical unlikelihood of their loss. The suicide myth, wrote the vice president who authored the note, "seems to have taken on a reality of its own, independent of the facts." Six years later, after another death, a university trustee asked President Rhodes -- who, at the time of his retirement in 1995, was the Ivy League's longest-serving president -- at a meeting of the executive committee if the gorges were influencing the number of suicides. Firearms, the president reflected, yes; but the gorges? No.

At around the time Mark Sherman enrolled at Cornell, Jakub Janecka, the 2008 victim, was born in Uherské Hradiště, a town on the Morava River in the former Czechoslovakia. In the 1980s, the Janeckas immigrated to Honesdale, about 30 miles northeast of Scranton. While his siblings adjusted well to American life, Jakub struck his teachers as plainly intelligent, but implacably frustrated. "He was a good boy, a serious boy, who puzzled over the big questions in life," wrote Robert Simons, an English teacher at the local high school. "Perhaps more accurately said, he attacked the big questions in life." Jakub's thick accent, strange style of dress and sharp mind intimidated some of his classmates, one friend remembered. Unlike his friends, Jakub never dated. He was drawn into occasional fights with locals. Eager to leave Honesdale, Jakub decided on Cornell University, where his older brother was already studying.

Few people on campus remember Jakub Janecka. Those who do use words like "quiet" or "withdrawn." "His brother made more of an impression," said Stephen H. Zinder, a professor of microbiology who had been Jakub's advisor. "Jakub was a quiet, reserved type of student. It's not like he made some big impression." Another professor who taught both brothers said in an e-mail message that he too remembered the older brother well, but didn't remember much about the "latter Janecka," adding that he was "much less engaged."

Student records confirm as much. While it wasn't a blemish-free transcript, according to Bonnie Comella, director of advising and operations for the Biology Department, Jakub's grades raised no red flags. He enrolled in the fall of 1993, and after a leave of absence in the fall semester of 1995, stayed through the summer. The next fall, Jakub spent a semester at sea, traveling from St. Croix to the Netherland Antilles and Honduras. Although he graduated in the spring of 1998, Jakub stayed in Ithaca for the next two years, taking classes and working on campus. "He had been a sort of introverted extrovert," remembered Christopher Morris, a friend who played rugby with both of the Janecka boys. "He loved being with friends and having a good time," Morris said, "but there were times when he was quiet, and people wondered if he was still here."

It was in Mann Library where Jakub met Tom Clausen, a Cornell librarian. In 1997, and then again in 1999, Jakub found work at the library. "Very respectful, very quiet-natured," Clausen remembered of Jakub, when we spoke last year behind the circulation desk. "He didn't have a demonstrative personality." In May of 2002, Jakub sent word by e-mail that he had been abroad in the Czech Republic, but was hoping to apply to graduate school in the U.S. "The conditions there weren't that good," Jakub wrote. "I'm e-mailing to ask you if you would be willing to write a letter of recommendation for me?" Clausen was surprised by the request, since he had never directly supervised Jakub, but agreed nonetheless. Over the next three years, as Jakub vacillated between numerous schools and degrees, he called on Clausen with almost startling regularity for recommendation letters. In 2002, it was for a master's in education; in 2003, for the AmericaCorps Volunteer program, but by December, a PhD program in biology; and finally, in 2004, for both a PhD and a master's in biology.

Jakub settled finally on a graduate program in theology at the University of Scranton. "I am really enjoying it as it is very interesting," he wrote Clausen. "So things are going well." Along with his response, Clausen included a few of his own original poems, one of which described "hemlocks lean[ing] out over the river," and another, "taking in the river view/I see my feelings for this life/quite like the trees/leaning slightly downstream."

"Thanks for the poems," Jakub responded,

I really enjoyed them especially the two that had the river in them. They reminded me of when I used to work by the Delaware River and the way the flow of the river felt both somewhat wistful and also soothing, so that it also caused real ambivalent feelings in me, on the one hand a kind of liberation on the other a kind of regret, like those poems.

Regards,

Jakub

At Scranton, Charles R. Pinches, Chair of the Theology Department, remembered Jakub as a frequent visitor to his office. "He would get on certain matters that were always puzzling me," Pinches said, "They were genuine, no question. They were pressing, I suppose. But they also were kind of strangely ordered to me." Jakub told Pinches that he "wanted to know about spiritual life and biological life both," and upon graduation, would be applying for a masters in biology. With some reluctance, Pinches agreed to write Jakub a letter of recommendation.

In 1994, after a fifth student died in the gorges in the span of three years, the New York Times came to campus. The latest victim, who had graduated a few months earlier, jumped early one morning after a late night of drinking. Coming on the heels of an accidental fall two weeks before, the Times reported, "university officials, worried about the numbers of student deaths, were striving to counter the growing impression that there was something peculiar about Cornell that led its students to take their own lives at a higher rate than elsewhere." Aggravated by the bad press, one local alumna sent a scornful letter to the editor. "I suppose it is easier to invent some sort of mythological danger in the gorges on the Cornell campus or in the weather, or the cows," she said, "than to analyze what drives a young person to take his or her own life." In truth, the question of whether or not the gorges induce suicide, which has been debated internally for decades, remains unresolved.

By the numbers, Cornell does not have a suicide problem. When computing rates of student suicide, many colleges use 7.5 suicides per 100,000 students as a benchmark, a figure taken from the Big Ten Student Suicide Study conducted in 1997. For the total population between the ages of 15-24, the rate is higher: 9.9 per 100,000, according to the Center for Health Statistics for the year 2006. With 20,633 students enrolled in Ithaca as of this fall, Cornell should theoretically experience 1.5 student suicides per year. According to Timothy Machell, director of mental health initiative, there were 10 student suicides from 2000 to 2005, and three between 2006 and 2010, which puts Cornell beneath either average.

The misperception that Cornell does have a suicide problem, Machell said in an e-mail, "is due in part to the highly public nature of suicides in the gorges that run through our campus." Also, he said, unconnected gorge suicides are often assumed to be linked to the university. In the past few years, Cornell has taken an aggressive stance on mental health, training everyone from librarians to handymen to be on the lookout for signs of distress, to which Machell attributes the decline in student deaths.

Are the gorges, then, nothing more than a geographical idiosyncrasy, the noose or handgun writ large beneath campus? As Murphy, the vice president, acknowledged, the gorges "can be scary places at times like this." If the mythology that that fear breeds is indeed fallacious, then how should the university countenance its existence? And how to explain the enormous potency of the mythology -- "a feeling," as the Times wrote, "that if the gorges were not there, perhaps some of the suicides would not have happened." If there's no clear answer today, it's not for lack of interest.

In 1981, a professor of anthropology named James Siegel published interviews with pedestrians as they crossed the suspension bridge. Looking downstream, Siegel and his class asked the passersby how the view made them feel. One respondent answered simply, "I want to jump."

Q: How come?

A: Oh, not because right now it makes me want to jump so much as because it's just such a thing about these gorges.

Q: What do you mean? Because you have passed by so many times and thought things and that's what you think now?

A: No, no. It's the gorges and what there is about them.

Q: You mean the history and that you know that people jump?

A: Yes, the history but also just because of what I think added to it. I always want to jump.

Q: Well, what is it? Just look at it and say what it is.

A: Well, it's so far down. And it's water you know and somehow it seems a beautiful way to die. To go out with it.

For Siegel, the "frequent mention of death and particularly of suicide" he encountered was "often a function of the logic of sublimity." In 1764, Immanuel Kant speculated that anyone who beholds "deep gorges with raging streams in them, wastelands lying deep in shadow and inviting melancholy meditation, and so on is indeed seized by amazement bordering on terror, by horror and sacred thrill." Under such circumstances, thought Kant, a man would be "diminished to insignificance," seeing only the "misery, peril, and distress that would compass the man who was thrown to its mercy." As his subjects contemplated the downstream abyss, Siegel noted, the thought of suicide was eerily comforting.

At bottom, the question for Cornell is not whether the gorges afford a dangerous outlet for the disconsolate or disturbed (by all accounts, they do). It's if, absent the gorges, some of the suicides could be avoided. Common sense suggests, as one official told the Times in 1994, "if you put a barrier up on a bridge, that people won't die from that bridge. Even if barriers were installed, people could just go somewhere else." That's the same thing people said about the Golden Gate Bridge, until a landmark 1978 study proved otherwise. To test the hypothesis that people thwarted from committing suicide "would simply and inexorably go someplace else to commit the act," Richard H. Seiden, then a professor at Berkeley, tracked down 515 people who attempted suicide but were restrained. His findings showed that 90 percent of the would-be victims did not later die of later suicide attempts, and that the notion that "attempters will surely and inexorably 'just go someplace else,' is clearly unsupported by the data." During the debate in the late 70's over suicide barriers in Ithaca, the director of suicide prevention at the time, Nina K. Miller, cited Seiden's data in a Letter to the Sun's Editor. "I hope we can persuade those who are most opposed to the barriers," Miller wrote, "to examine some of the data which indicates such barriers are effective anti-suicide measures." Thirty years later, Machell says, "Suicide can be prevented, and limiting access to the means to die is one part of the equation." But "most importantly," he said, is a comprehensive approach that emphasizes education, counseling and support services.

Would heightened barriers or enhanced security have mattered for Jakub Janecka? Some think not. "It seemed like he must have come back here with a very clear intention," says Tom Clausen. Over the years, Jakub had visited Ithaca from time to time, always calling on Christopher Morris's father, the late M.D. Morris, when he arrived. On Jakub's last visit, Morris heard nothing.

Jakub arrived in Ithaca on Oct. 7 carrying only a small black nylon suitcase, with very little clothing inside. He checked in at a gloomy stopover at the foot of campus called the Hillside Inn. There, said the desk clerk, he would shuffle by without returning the clerk's greetings. "He was so interiorized, so introverted," the clerk remembers, "it looked like he was in a mental mess." His condition was no different the next day. On the bridge that afternoon, unlike so many who had hesitated at the precipice, Jakub was quick and decisive. Witnesses said he jumped headfirst.

But if he never intended to return that evening to the Hillside Inn, then why was Jakub carrying a key for Room 202? And what use would he have had for the $271 in cash police found in his pockets? Jakub paid upfront for a three-night stay at the inn, according to the clerk, which was two more nights than he needed. And a suicide note? Nothing but a small notebook with several local numbers inside, which, when the inspector followed up, were for local landlords and employment services. Jakub had no mental health issues, his family told police, although after finishing his master's degree in biology at the Catholic University of America, he was depressed due to a lack of employment -- the very reason, they said, why he had come to Ithaca in the first place.

In the gorge, mouth agape, arms spread, and shirt scrunched up past his stomach, it seemed to onlookers like Jakub might just be taking a nap. The white ball cap had fallen ten feet away. A few inches of water flowed underfoot. In the years after his graduation, Jakub was consumed by an apparent wanderlust, for answers to unformed questions, until finally "his searching must not have felt worthy anymore," says Clausen. His English teacher, Robert Simons, wrote, "Not having followed his life into manhood, we can only assume that he continued to be a searcher after he went out of our view."

Especially in this day and age, cries for help come in any number of ways. The week before he died, Matthew Zika, the most recent victim, posted a poem he had written on Facebook. It was, he said, "the culmination of one week of doing nothing," penned instead of completing a problem set. About waking up, or trying to, Zika ruminated:

Something's in the way, though

ducttape binding my arms,

holding me from reaching the light switch

that could shed light on this isolation

chamber. but who am I

to suppose correct wiring.

For all I know, the light bulb

is dead.

So here I sit, instead.

Then, on March 9, at 2:03am, Zika updated his Facebook status with a portentous message. "My hope in living life," he wrote, "is that if one day someone told me it would be my last, I could smile and nod knowing full well that I did all I could with the time I was given. Never put off until tomorrow what you'd be okay having never done." On Friday, after his death had been reported, a friend posted to Zika's wall, "I think you mean never put off until tomorrow what you wouldn't be okay having never done."

Yet for all the red flags planted in Zika's profile, a close inspection of Bradley Ginsburg's Facebook account would have yielded little cause for concern. Responding to a friend in October, Ginsburg wrote that "everything's great," and that "it's sick here." "There's mad frat parties," he continued, "the campus is ridiculously nice, my classes are pretty cool, and everyone's really chill." The workload was heavy, Ginsburg concluded, "but it's definitely worth it."

In the 1970s, an alumnus named Howard Cogan created a slogan for the ten square miles of his hometown he said were "surrounded by reality": ithaca is gorges. Emblazoned today across apparel, mugs and bumper stickers on campus, in town, and even across the world, the catchphrase has become a kind of catchall for the small city. So when tragedy strikes, it's not in Ithacans' nature to search the proverbial wall for clues; the handwriting's right there on the tee shirts. "Cornell is a river of students," Hubbell said, "a city of eternal youth." Far above Cayuga's waters, the people of Ithaca look on their gorges as neither quirk nor quiddity -- but just what the pun says: gorgeous. "As a townie and alumna," one disgruntled resident wrote some years ago, "I take exception to your blaming my beautiful gorges for just being there. Ezra Cornell must be turning in his grave, having searched for the most beautiful place to found his institution, where any person could find instruction in any subject," she said, quoting the university motto.

"I don't think suicide was quite what he had in mind," she wrote, "when he placed Cornell high above Cayuga's waters."