What does an artist (or any human being, for that matter) do after realizing he has been channeling his creativity to fulfil someone else's expectations? In an art world where the difference between fashion and art is blurrier than ever, this is not a minor question. Richard Diebenkorn's retrospective at the Royal Academy of Art in London shows the work of an artist who dialogues with other artists only to make it clear that his art is neither trendy nor visionary. With pigments he walks that cornice that separates presentation and representation; abstraction and figuration; cartographic description and naturalism.

Although the Royal Academy show is wonderful, its catalogue is pedestrian and, worse of all, far too clinical. Steven Nash seems to set the tone by focusing, as if this truly mattered, on Diebenkorn's European influences which range from Henri Matisse to Carl Friedrich. But Diebenkorn is a Californian Abstract Expressionist in a country that doesn't take the West Coast as a serious place for human beings to reach artistic level.

The retrospective mirrors Sarah Bancroft's essay where his work is organized along three major periods and roughly four series. This provides some context for the locations in which he produced his most important work, as he vacillated between abstract pursuits, figurative explorations and then back to abstraction over more than four decades. Even though the regions in which Diebenkorn worked -- their climate, light and space and sense of place -- had a perennial impact on his sensibility and artwork, his paintings transcend the context of their production and that is where, in my opinion, the Royal Academy misses the point.

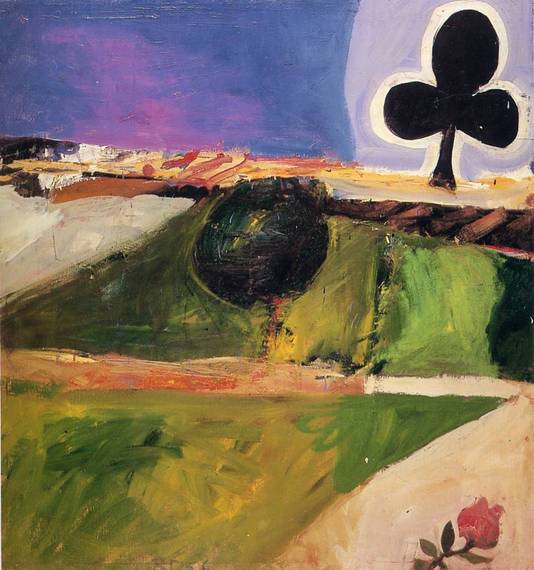

His Albuquerque and Urbana paintings (1950-1953) are all about the disintegration of the figure both as still life and landscape. The show opens with "Disintegrating Pig" (1950) where we can see how abstraction is not a purely intellectual pursuit but also a naturalistic one. Maybe this is the reason why in "Albuquerque 4" (1951) he places a Cross of Malta so as to juxtapose the realm of the symbolic as icon and as sign. From that moment onwards the use of red, lavender and all hues of terracotta are so obviously linked to the Californian desert that the Royal Academy's insisting on this point comes across as redundant. There is an aspect that I found particularly American about this series and is the conflation of landscape painting and abstraction. If Arshile Gorky and Williem De Kooning reached abstraction through the disintegration of still lives and figures, Diebenkorn seems to do so taking the landscape as a starting point. Having said this, this artist explores the way the land is visually represented in times of not only westward expansion but also in times of cartographic revolution. Thus, it does not come as a surprise to know that during the Second World War, Diebenkorn worked as a cartographer. This is evident in the Urbana series. What is also evident, however, is how pigments are deployed so as to convey duration (the fresh paint sometimes create a trial) and error. As a matter of fact, his paintings are messy, inexact and most of all, very human. It is as if Diebenkorn explored the limits of cartographic and photographic representation from the point of view of human experience.

In his Berkeley series (1953-66) he goes further in this direction only to find himself against a wall. It is then when takes an apparent 180 degrees turn and embraces figuration. There was no external exegesis for such a bold move, and certainly no commercial pressure; indeed, quite the opposite may have been true. In times when abstract expressionism became the canon, he turns to a painterly figuration that is reminiscent of Henri Metisse. This new direction was a veritable sea-change within his work and the variety of work he produced after the transition grew to include large figure and still life paintings, landscapes and cityscapes and small still life paintings (that Wayne Thibaud might have used to get inspiration). It is from this time that we have "Seawall" (1957) where painting is used as tectonic chunks that transform color into pure matter. From the point of view of his iconography, he tends to depict isolated objects and self-absorbed sitters conveying a sense of melancholic inwardness. It is this beautiful sadness that I found particularly appealing. If the eyes are the windows of the soul, Diebenkorn paints his figures without eyes.

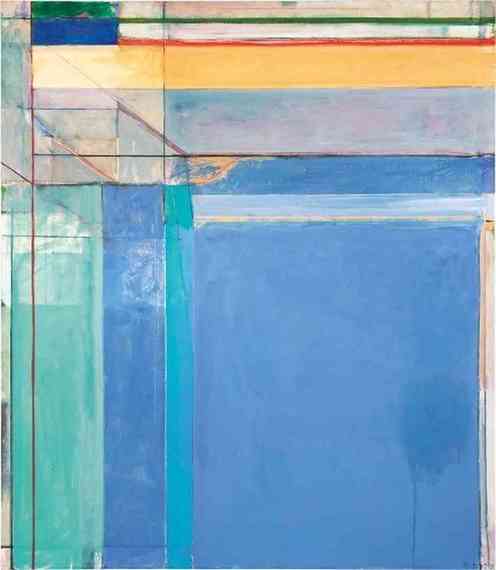

It is in 1967 that Diebenkorn goes back to abstraction and it is in the dialogue that he establishes with Piet Mondrian where this show triumphs allowing us to see his whole journey backwards. Even though it could be said that his latest paintings are abstract and cold, they are all about human error, erasure and correction. According to Diebenkorn life is a learning journey through which we must get in touch with our darker side in order to accept the often underestimated beauty of contentment.