In a recent New Yorker story called "Rush," a South Indian man says of his region's growing East Coast Road, "Civilization only kills. I was much happier before we became civilized." His wife, similarly devastated by their teenage son's death in an automobile collision but recalling nights in a thatched hut surrounded by howling jackals, has a more nuanced take -- the highway should be safer, its drivers better trained.

I'll be the last to romanticize the rustic and the first to appreciate a paved road. Highway 54 in southern Kansas, visible on the flat horizon from my upstairs farmhouse bedroom, eased a portion of the hour-long bus ride to and from my crucial public education. (In a handful of years, I experienced three school-bus flips and crashes on muddy, snow-packed or deer-frequented dirt roads.) After school I often drove one of our Honda "three-wheelers" first to the cattle pasture with feed buckets and then miles away to the closest county bridge over 54; I'd park the ATV, climb onto the concrete safety barrier and dangle my legs. When eighteen-wheelers zoomed toward me at 80 miles per hour, I'd pump an arm in the air and clutch the railing as they whooshed beneath my feet, their friendly honks echoing from beneath the bridge, my hair lifting toward the sky on swift gusts. It was a rush, as was the day I drove that same highway toward the University of Kansas in Lawrence, the hilly, treed town I now call home in the northeast corner of the state.

There, in coming weeks, construction of the South Lawrence Trafficway -- six miles of broad highway meant to circumvent the college town -- is set to violate a broad swath of the Wakarusa Wetlands, 640 acres of hydric soil rich with biodiversity and cultural significance. Following decades of legal battles, the $150-million project finally would join existing stretches of Kansas Highway 10 to east and west of Lawrence. The southern loop would provide a handy bypass for semi-truck drivers and other commuters between Kansas City and Topeka (most efficiently linked at present by more northern points along Interstate 70). Environmentalists, biologists, indigenous tribes and others have been fighting for an alternate route since the 1980s; some of them occupied the area, recently sliced by a wide, mowed path marked for digging, Oct. 25 to 27.

As Akash Kapur's New Yorker story demonstrates, progress is in the eye of the beholder. In many American cities, strategically charted 20th-Century highways represented "urban renewal" for white-collar commuters but meant, in James Baldwin's words, "Negro removal" for established black neighborhoods suddenly isolated from goods and services. To small towns, highways have been what railroads were during the 19th Century: economic life or death. (Tift Merritt describes the latter conundrum in a song perhaps inspired by Bynum, N.C., the former cotton-mill town where she got her start: "They laid a highway a few years back/ Next town over by the railroad track/ Some nights, I'm glad it passed us by/ Some nights, I sit and watch my hometown die.")

The South Lawrence Trafficway means destruction not for neighborhoods or industries but for one of three sensitive wetland ecosystems in Kansas. Points on quantitative ecological losses and conservation merits are best left to scientists and groups such as the Sierra Club, which called the would-be highway one of the 50 most environmentally offensive projects in the country. But many Kansans have become experiential experts on the Wakarusa Wetlands area -- by leaving our computers and cars and entering it.

We've witnessed its snakes, herons and turtles, touched its grasses in their tall autumn season and worn its spring mud on our feet. We've watched its flowers open toward the sun, its foxes and owls move in and out of sight with the moon. We are qualified to speak of its value and its life forms, who suffer greater dearth of habitat than do we of asphalt thoroughfare. Where will they go? It's a question imperialists and capitalists historically ask as afterthought and answer in whatever manner suits their purposes -- as indigenous tribes, African Americans, agricultural communities, the inner-city poor and others know all too well.

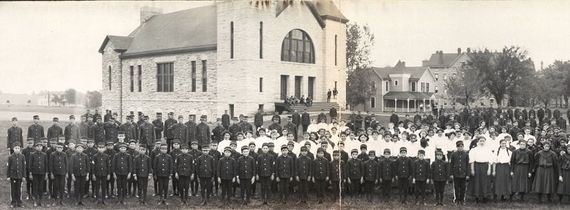

The threatened wetlands border Haskell Indian Nations University, a four-year institution that opened under very different purposes in 1884 as the United States Indian Industrial Training School, a federal outpost for cultural genocide. The swampy area at the southern edge of the existing Haskell campus is held in memory and ceremony as a place to which terrorized children escaped to speak forbidden tongues, practice forbidden customs, remember themselves, find family members. Haskell students reportedly died from disease, abuse or suicide; a small campus cemetery contains more than a hundred of their bodies, but many were thrown, tribal elders say, into the wetlands.

State consultants, after reviewing such reports by trafficway objectors, said insufficient evidence existed for halting the project; in 2012, a federal appeals courts made way for construction to begin. Officials have promised the highway won't dig into deep soil and that tribal representatives may attend excavations. If construction workers hit human remnants, officials have said, they will stop, notify police, call the state archaeologist. As for environmental considerations, about $23 million of total funds have been earmarked for tending surrounding areas and constructing new wetlands and an education center. (Since 1968, nearby Baker University has owned most of the wetlands area and used it for field research and education programs, while much smaller sections belong to Haskell, the University of Kansas and the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism.)

No habitat goes unchanged, and our species is a flicker in infinite transitions of place. But we choose what role we play in that unfolding, and our choices reveal what we value, what our highways mean to us. An improved life? For whom? In the case of the South Lawrence Trafficway, many commuters may enjoy an even faster transit. Wealthy developers and corporations will garner much of the projected $3.7 billion in commercial impact. An ecosystem will suffer, increasingly so as the highway gives rise to surrounding development. And, should construction machinery strike human remains, children's bones will be disturbed by civilization for the second time.