Picking up three to six House seats in California's congressional delegation is instrumental to the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee's stated goal of flipping at least 25 Republican seats nationwide and retaking control of the House of Representatives in 2013. However, the results of the Golden State's first-ever "jungle" primary on June 5 suggest this may be an uphill battle.

There are reasons to expect that the major parties' respective shares of the two-party vote in jungle primary races will resemble their shares in the general election races that follow. That is to say, if Democrats A and B together receive 52 percent of the two-party vote in a jungle primary, it might be expected that Democrat A who advances to the general election will receive something close to 52 percent of the two-party vote against a Republican opponent in that election. This expectation is rooted in the fact that, in jungle primary races, all candidates compete on one ballot regardless of party, all voters are allowed to participate regardless of party, and the top two vote getters advance to the general election regardless of party. Accordingly, the results of jungle primary races, unlike party primary races, reflect the preferences of not just party voters but also independent voters. Moreover, jungle primary races are unlike party primary races in that all a party's candidates are eliminated from further contention if none of them finishes first or second. Thus, as long as there are more than two candidates contesting an office on a jungle primary ballot, voters from both major parties have an incentive to participate in the primary, even if their party is fielding only one candidate or multiple candidates they are equally happy with. Independent voters also have an incentive to participate in jungle primary races to make sure their preferred candidate makes the finals.

On the other hand, there are reasons to expect that if there is a jungle primary race that is more strongly contested on one side of the partisan ledger, for example, where one of the major parties (but not the other) fields multiple primary candidates, the parties' respective shares of the two-party vote in that primary race might not be quite as predictive of their general election shares. In such races, members of the party that is fielding multiple primary candidates have an added incentive to participate in the primary, especially if they have a strong preference for one of the candidates. Moreover, strategic voting can be a factor in such races, whereby crossover and independent voters cast their primary ballots for one of those candidates even though they have no intention of voting for him or her in the general election. The net result is that the share of the two-party primary vote of the party that fielded "excess" primary candidates may overstate the share that party will realize in the general election.

Summarizing, then, one might expect that A) as a general matter, the major parties' respective shares of the two-party vote in jungle primary races will be predictive of their respective shares of the two-party vote in the general election races that follow; and B) in jungle primary races where the race is more strongly contested on one side of the partisan divide, often reflected in the presence of a larger number of candidates of that party on the primary ballot, the share of the two-party vote garnered in the primary by that party's may overstate its share of the two-party vote in the general election.

These expectations are largely borne out in 175 congressional, state senate, and state house races conducted under Washington's jungle primary system in 2008 and 2010 where a Republican and a Democrat advanced to the general election. In those races, the share of the two-party vote realized in the general election by each major party's advancing candidate was correlated with his or her party's share of the vote in the primary, reduced in relation to the excess number of candidates fielded by his or her party in the primary. A small caveat is that, all else being equal, Democratic general election candidates tended to slightly outperform their party's two-party share of the primary vote (i.e., by a little more than two points, or a "swing" of a little more than one point).

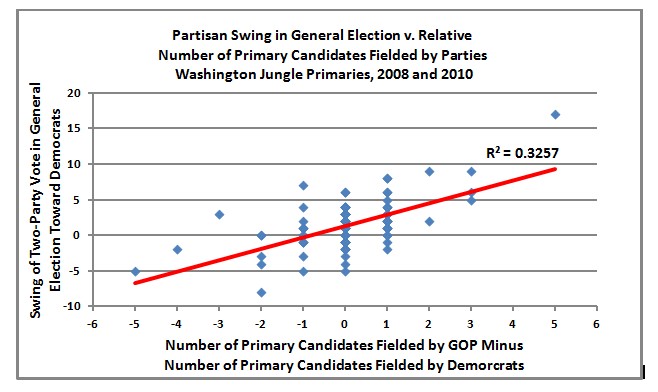

The following chart shows the results across the Washington jungle primary data set. (There are fewer than 175 data points due to substantial overlap of data, mostly near the trend line.)

Taking a specific example, in a 2008 or 2010 primary race where Washington state Republicans fielded three candidates who together received 60 percent of the vote, compared with 40 percent garnered by two Democrats, an expected general election result would be a swing of three points toward the Democrat who advanced to the general election, such that the final tally would be in the neighborhood of 57 percent for the Republican and 43 percent for the Democrat.

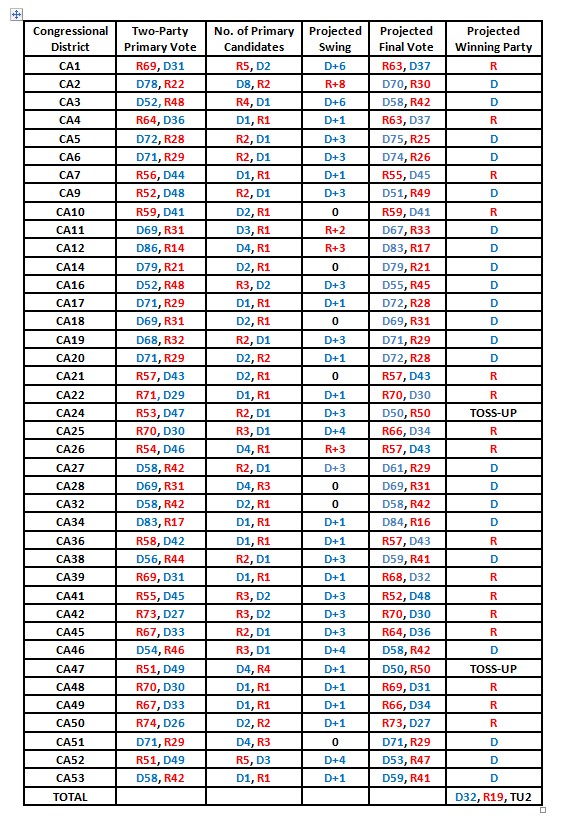

Now, let's assume for present purposes that these rules of thumb that held sway in Washington in 2008 and 2010 are applicable to California's congressional elections in 2012. At present, the California congressional delegation is comprised of 34 Democrats and 19 Republicans. After the June 5 jungle primary, the Democrats have already won nine seats and the Republicans have won three seats by virtue of either an incumbent running unopposed or two candidates from the same party advancing to the general election. In one other race (CA33), we will assume that long-term incumbent Democrat Henry Waxman will survive a challenge by independent Bill Bloomfield. That leaves 40 House seats up for grabs in the general election. If we assume for these 40 contested elections that the two-party general election vote will swing in relation to the parties' respective numbers of primary candidates in accordance with the trends witnessed in Washington in 2008 and 2010, the projected outcome of these 40 contested House races will be as follows:

Application of the "Washington model" presented here suggests that it will be difficult for the Democrats to reach their goal of three to six pickups in California's congressional delegation. The model predicts that the Democrats will win 32 seats and the Republicans will take 19, with two pure toss-ups. If we allocate both of the pure toss-ups to the Democrats, the tally becomes 34 Democrats and 19 Republicans -- no change from the current partisan composition of the delegation. If we evenly apportion the toss-ups, the Republicans gain a seat. And it bears noting that this projection assumes a general election swing toward Democrats that will net them at least two seats (CA9 and CA52) where the GOP candidates cumulatively received a larger share of the two-party vote in the June 5 primary.

Of course, none of this is written in stone. The model applied here is fairly simplistic and is patterned on races in only two election cycles (one presidential, one not) in a single state that is not as deep blue as California. The model doesn't account for the quality of individual candidates and their campaigns, which will play a decisive role in some races. But if it turns out that Washington's jungle primary past is prologue for California, the DCCC's California dreams are unlikely to materialize.